Bit Manipulation

I’m still working on my coding problems, and in this post I want to talk about bit manipulation in Python. I’ll start by reviewing binary representations in computers and then dive into talking about binary operators and bitmasks, two key tools for manipulating bits on a computer. Let’s get started!

Why do Computers Speak in Binary?

Some of this is probably review for a lot of folks, but I just wanted to set the context of this post by talking about why computers use binary to encode information. I think it’s interesting to consider what drove the decision to use binary and how it impacted everything else about how computers work. Binary is a form of positional notation, because the position of each digit helps to convey information about the value of that digit [1]. For example, in base-10, 1.0 and 10.0 are different values because the position of the 1 has changed. Binary is base-2, that is, each shift in position increases the value of the number by a power of 2. For example, 1 and 10 in binary represent 1 and 2 in our base-10 system.

The reason why computers use base-2 instead of base-10 is that base-2 is more robust to hardware issues. The base-2 system only has 2 digits, 1 and 0, and this correlates nicely with having an electrical signal that is either on or off. If we used base-10, then computers would need to be able to detect 10 different voltage levels in the electrical signals, and it can be difficult to build hardware that can do that reliably and robustly, especially in the presence of noise. But base-2 is much easier to implement in hardware because we just need to know if the electrical signal is on or off [1].

At the most fundamental levels in a computer, all information is encoded in the binary format. For example, the text that you are reading right now is comprised of characters that each have a unique binary encoding [1]. So given how essential binary is to how computers work, you can understand why being able to manipulate bits (each bit is one decimal place in base-2) is important in computer science.

Some Binary Basics

Before we move on to talk about bitwise operators, I want to cover some important aspects of how binary encoding works, specifically when implemented in Python. First of all, generally speaking we represent data in bytes, where 1 byte consists of 8 bits. Recall that each bit is a decimal place in the base-2 numbering system, so the maximum value that 1 byte can represent is $2^8 = 256$.

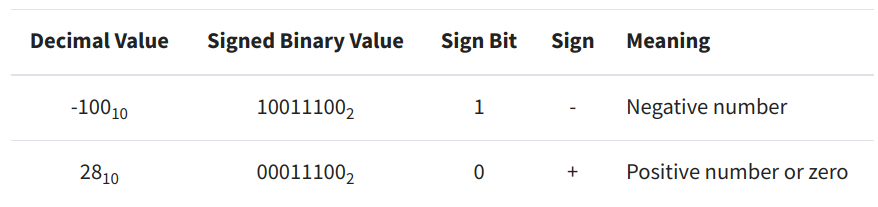

It is also possible to distinguish between positive and negative numbers in binary. Typically, this is done using an extra bit at the far left of the byte which is 0 for positive values and 1 for negative values. This is shown in Figure 1. Note that Python does not follow this convention, however, and so that affects some of the bitwise operators we will see in the next section. Specifically, Python allows for using an unlimited number of bits to represent an integer, so this forces it to use a different method for representing the corresponding sign of the integer [1].

Figure 1 - Source [1]

Note that Python allows you to see how integers are represented in binary and other schemes. For example [1]:

bin(42) = 0b101010 # 0b is the prefix indicating the representation is binary

hex(42) = 0x2a # 0x is the prefix for the hexadecimal system

oct(42) = 0o52 # 0o is the prefix for the octal system

Two’s Complement

For languages other than Python, integers are typically stored in a form known as two’s complement. In two’s complement, the positive integers are stored as expected in binary, and negative integers are stored as the two’s complement of its absolute value. Two’s complement uses a sign bit (i.e. the left-most bit) to indicate if the number is positive (0) or negative (1) [2].

Let’s understand what the two’s complement is. The definition of the two’s complement is that, for an N-bit number, it is the complement of that number with respect to $2^N$. For example, let’s try to represent $-3$ in two’s complement notation. We will use 4 bits to encode $-3$: one bit is for the sign, the other 3 bits are for encoding the value. Therefore we have $N = 3$ bits and so we need to find the complement of 3 with respect to $2^3 = 8$. The complement of 3 with respect to 8 is $8 - 3 = 5$. In binary, we can write 5 as 101. So, in full, the two’s complement notation for -3 is 1101 (the left-most bit is 1 to indicate the number is negative) [2].

Put more generally, if we want to find the two’s complement of a negative integer $-K$, then we need to perform [2]:

concat(1, 2**(N-1) - K)

Another way to find the two’s complement of a negative integer is to [2]:

- Flip all the bits

- Add 1

- Prepend 1 to indicate the value is negative

Bitwise Operators

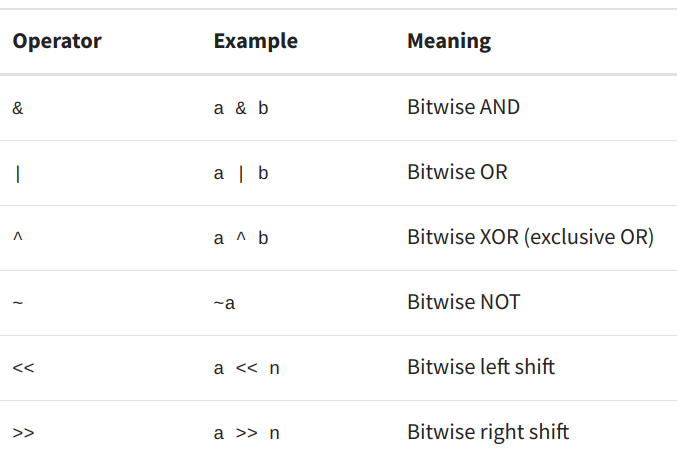

We can operate on individual bits using a number of different logical operators in Python. A summary of some of the common operators is shown in Figure 2. Most of the operators (with the exception of the NOT operator) are binary, which means that they compare the left operand to the right operand - for example they determine if a and b are true. The bitwise NOT operator is a unary operator since it only takes in one operand [1].

Figure 2 - Source [1]

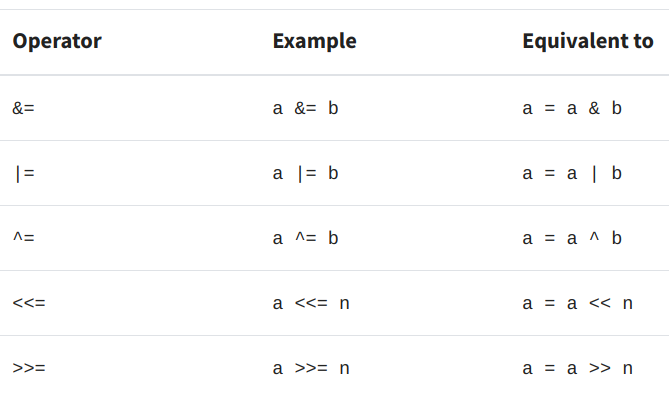

All of the binary bitwise operators have an accompanying compound operator, as shown in Figure 3 [1]. The compound operator performs the bitwise operation, and then assigns the result of that operation to the left operand. I find that the compound operator reminds me of incrementing a variable: i += 1 because I am taking the variable i, adding 1, and assigning the new value to i.

Figure 3 - Source [1]

Let’s explore some of these operators in more detail. I would also recommend heading over to [1] to see some very helpful GIFs that make it easy to visualize what these operators are doing.

AND

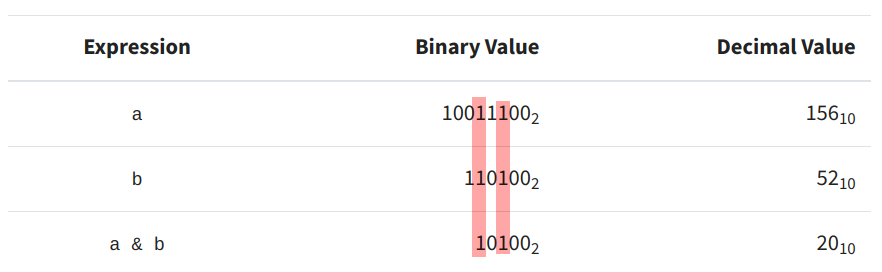

The bitwise AND operator compares two operands and returns a 1 any time the bit in the same position in both operands is on. Otherwise, it returns 0 [1]. An example of this is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 - Source [1]

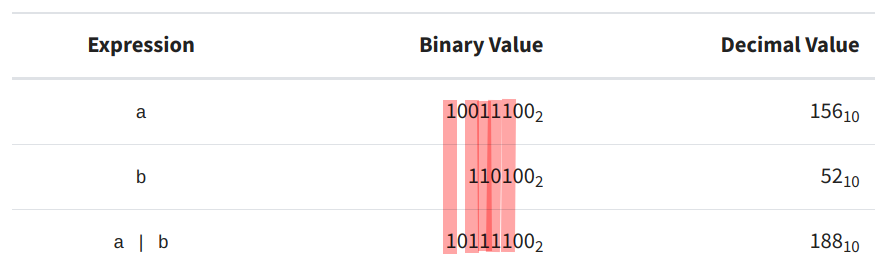

OR

The bitwise OR operator returns a 1 any time at least one of the operands has a 1 in a given position. The OR operator only returns 0 if both bits (from each operand) are zero [1]. This is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 - Source [1]

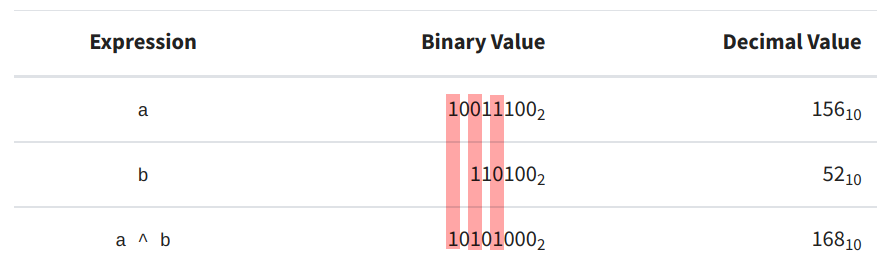

XOR

Interestingly, Python does not natively support the XOR operator. XOR stands for “exclusive or.” The XOR operator returns a 1 if the two operands have different values at the same bit position. It basically tells us when two operands represent two mutually exclusive cases. For example, XOR would return a 1 if one operand had a value of 0 and the other had a value of 1. If both operands have the same value, then XOR returns 0 [1]. This is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6 - Source [1]

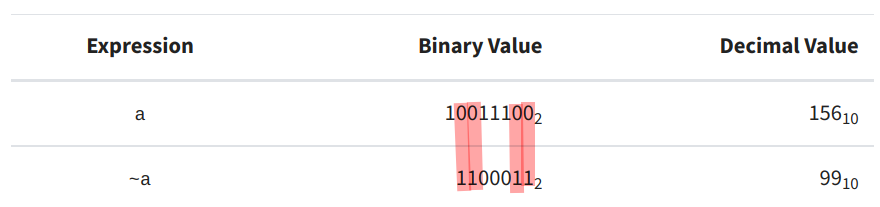

NOT

Finally, the NOT operator simply reverses the value of every bit in the operand. However, it is worth noting that the NOT operator does not always work as expected in Python, because Python uses unsigned integers [1]. For now, admire this image depicting how the NOT operator works.

Figure 7 - Source [1]

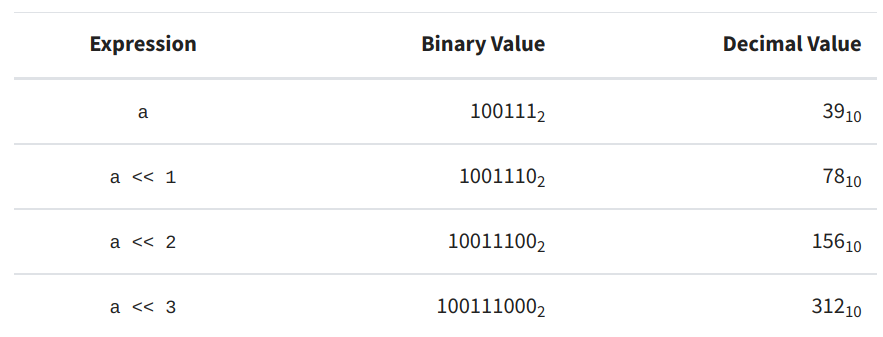

Shift Operators

There is another category of bitwise operations that shift binary numbers to the left and right. This is a very efficient way of manipulating numbers and can be used to make bitmasks, which we’ll discuss later. The left shift operator, <<, moves the bits of the first operand as many places as specified in the second operand [1]. For example:

1100101 << 2 = 110010100

Every time we shift the operand one place to the left, we double its value, as shown in the table below. Bit shifting in this way used to be a popular way to quickly compute products or exponents, but Python is now very efficient and doing this bit manipulation manually is unnecessary. Notice also that Python is intelligent enough to know that if you shift the first operand to a size greater than a byte (8 bits) that we should increase the storage size of that number so we can represent it accurately. However, other languages may not do this and so you might find that you shift a value to the left and some of the bits are chopped off, returning a smaller value than you wanted [1].

Figure 8 - Source [1]

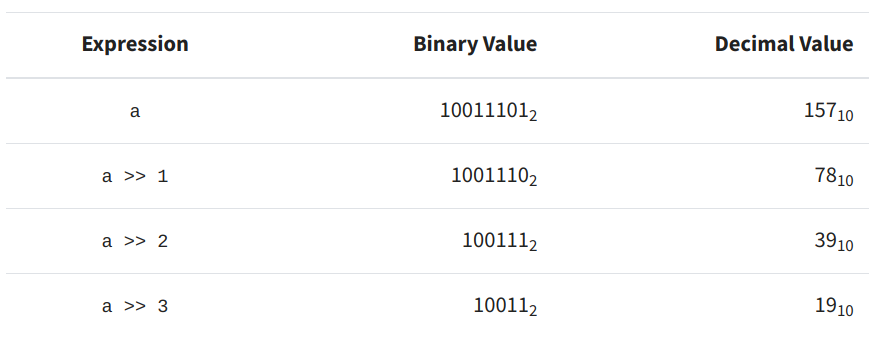

Shifting values to the right instead of the left is the same operation, but now every time you shift the bits one place, the value of the number is halved instead of doubled, as shown in Figure 9. Notice also that when shifting (i.e. dividing) an odd number, the value is rounded down to the nearest integer (i.e. we do floor division) [1].

Figure 9 - Source [1]

One thing to notice here is that the right shift operator can affect the sign of a number. Recall that the left-most bit is often used to convey the sign of the number the byte represents, and so if you right shift the bits, the left-most bit always becomes a 0 [1].

So far, the left and right shifts we have discussed are called logical shift operators, which means that they just move the bits without taking into consideration things like the sign of the integers that are being manipulated. There is another category of shift operators - arithmetic shift operators - that performs the right shift while taking into account the sign of the integer. The arithmetic right shift, therefore, maintains the sign bit when it shifts the rest of the bits to the right [1].

Bitmasks

Bitmasks can be used to manipulate specific bits in a value. For example, you can force Python to represent the sign of an integer using the left-most bit by manipulating the integer with a bitmask. For example, if you perform the AND operation on an integer and a corresponding bitmask, you get the following [1]:

mask = 0b11111111 # equivalent to 0xff

bin(-42 & mask) = 0b11010110

Notice here how the bitmask is overlaid on top of the value in question to obtain some information about its binary representation. There are some other useful operations that we can perform with bitmasks as described below.

Getting a Bit

If you want to read the bit at a specific position in a number, you can use a bitmask to obtain it as shown below [1]:

def get_bit(value, bit_index):

return value & (1 << bit_index)

get_bit(0b10000000, bit_index=5) = 0

get_bit(0b10100000, bit_index=5) = 32

Here, the bitmask is 1 shifted over by bit_index number of places. The function then returns the value (in base-10) of the bit at that index. If you wanted to get the normalized value (i.e. just a 1 or 0), then you could use this function instead [1]:

def get_normalized_bit(value, bit_index):

return (value >> bit_index) & 1

Here we right-shift value until the bit in question is at the first position, and then we retrieve it using a bitmask of 1.

Setting and Unsetting a Bit

You may also want to set the value of a specific bit, which you can do using a similar function to the one shown above, but using the logical OR operator instead of AND [1]:

def set_bit(value, bit_index):

return value | (1 << bit_index)

set_bit(0b10000000, bit_index=5) = 160

bin(160) = '0b10100000'

Since we are using the OR operator with 1 as the right operand, we are setting the bit at bit_index to have a value of 1 regardless of its current value. If you wanted to unset this value, you could do the inverse (i.e. use the NOT operator on the bitmask) [1]:

def clear_bit(value, bit_index):

return value & ~(1 << bit_index)

clear_bit(0b11111111, bit_index=5) = 223

bin(223) = '0b11011111'

The NOT operator in Python always returns a negative number when given a positive number as input, but using the NOT operator in concert with the AND operator changes the way Python represents the bitmask so that it works as expected in this situation. (For more detail on why this is the case, see the section on “Binary Number Representations” in [1].)

Toggling a Bit

Finally, you can toggle a bit to have the opposite value to its current state using the XOR operator and a bitmask [1]:

def toggle_bit(value, bit_index):

return value ^ (1 << bit_index)

Conclusion

I hope this was a helpful overview of how data is represented in a computer and how to manipulate individual bits. I expect that as I tackle some problems related to bitwise manipulation that I will encounter some more concepts that I need to learn, so stay tuned for further blog posts in this space.

References

[1] Zaczynski, B. “Bitwise Operators in Python.” Real Python. https://realpython.com/python-bitwise-operators/ Visited 13 Aug 2022.

[2] Laakmann McDowell, G. Cracking the Coding Interview, 6th edition. 2016. CareerCup, LLC.