Cooperativity is a Key to Life!

Lately I have been fascinated by the topic of cooperativity in biology, so I wanted to take this opportunity to share some of the things I have learned. First of all, cooperativity can be defined as a phenomenon where different elements in a system, which may seem completely independent of each other, will act together [1,2,3]. The really cool thing about cooperativity was that if it didn’t exist, biology simply would not function the way it does today. I just think there’s something really beautiful about how this invisible phenomenon that we observe acting at the smallest levels of biology has such a fundamental importance to all of life. In this post, I’ll describe what cooperativity is, different ways to model it and ways to study it experimentally. Let’s dive in!

What is Cooperativity?

I have been studying how cooperativity affects the formation of DNA nanotechnology structures, specifically how DNA strands bind, or hybridize, together. Some researchers in this field have investigated how cooperativity affects these assembly processes, and they generally draw on concepts developed in biology. Biologists have studied cooperativity for over a century, particularly in the context of how molecules, proteins and other ligands*1 bind together [1]. Cooperativity as a concept can describe how the different components in a reaction can help or hinder each other as a new complex is formed.

The classic experimental example for studying cooperativity is how oxygen binds to the protein hemoglobin, a reaction that is essential to transporting oxygen around the human body [1]. Hemoglobin has four binding sites for oxygen molecules, and experimental data suggests that as oxygens bind to the protein, later binding events are made easier and more likely by the earlier binding events [1,3]. In other words, The oxygen molecules are somehow cooperating with each other to make it easier for all four of them to bind to the protein. For example, each binding event might bend the protein a little (i.e. change its conformation) so that it is easier for subsequent oxygens to fit into their specific binding sites [1,2]. We’ll discuss this idea in more detail in a minute.

Before we dive into the different models for cooperativity, I wanted to take a minute to appreciate how important it is to biology and life as we know it. According to Levinthal’s paradox, when we consider protein folding, we can see that a given protein has a huge number of degrees of freedom which can be adjusted to achieve a given shape, or conformation [2, 6]. The time required to fully explore all of these degrees of freedom before finding the single stable conformation (or the small number of valid, stable conformations) is longer than the age of the universe [2,6]. Wow! But most proteins can fold into a stable configuration in milliseconds, because local regions of the protein interact with each other and drive the folding process towards the stable configuration [6]. These local interactions are driven by this concept of cooperativity - these local regions bind first and help adjust the shape of the protein so that other sections can also bind together and find an energetically stable configuration [2]. So without cooperativity, not even one protein in your body would have finished folding yet, even if you had been born the moment the universe began!

First Models of Cooperativity

Let’s look at how researchers “measure” cooperativity and model it in different ways. As we mentioned above, the oxygen-hemoglobin interaction is the experimental system that we studied initially to understand cooperativity. Let’s assume that a single oxygen bound to a hemoglobin protein, so that we could write the oxygen saturation in a hemoglobin protein at equilibrium as follows:

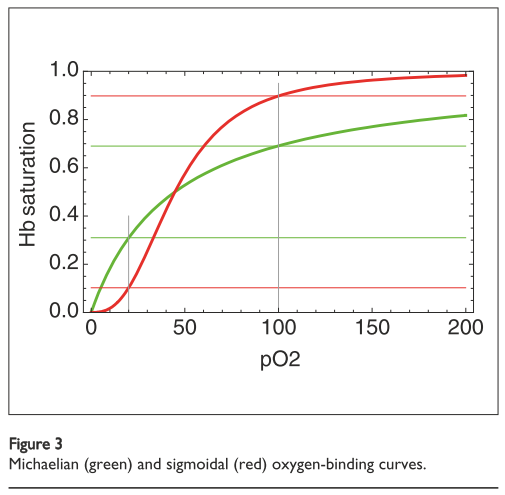

\[\gamma = \frac{x}{K + x}\]Where \(\gamma\) is the oxygen saturation, \(x\) is the concentration (or partial pressure) of oxygen and \(K\) is the dissociation constant. This is called a Langmuir equation because it is an equation of the form \(y = \frac{x}{1 + x}\) and has a specific hyperbolic curve shape, as shown in Figure 1 in green [7]. We also sometimes call it a Michaelis-Menten equation, which is an equation in the same form [1, 3].

Figure 1 - Source [1]

Since the purpose of hemoglobin is to take oxygen molecules from oxygen-rich regions (where the concentration of oxygen is about 100 torr) to oxygen-poor areas (where the partial pressure is closer to 20 torr), we want to carry as much oxygen per hemoglobin as possible [1]. Under the model given above, and as shown in Figure 1, only about 38% of the available oxygen molecules can be transported by hemoglobin to the destination regions. It would be useful if hemoglobin proteins could actually do much better than this.

And in fact, hemoglobin proteins do bind to more oxygen molecules than suggested by this very simple model. According to experimental data, the binding curve looks more sigmoidal (see the red curve in Figure 1) and has a wider saturation range [1]. At high oxygen concentrations, the hemoglobin binding capacity is higher than 100 torr so it can pick up more oxygens, and at lower oxygen concentrations the binding capacity of hemoglobin drops to lower than 20 torr, so it is more likely to completely dissociate with all bound oxygen molecules in that environment [1].

The significance here is that the sigmoidal curve is a tell-tale sign that cooperativity is at play [1,2,3]. Since the experimentally observed curve is steeper than the one we would expect for a simple single-oxygen binding event, there must be something happening that causes oxygen binding to be more favorable than expected. The Hill equation was developed to capture this sigmoidal behavior [1,3]:

\[\gamma = \frac{[L]^n}{K_ + [L]^n}\]Where \(\gamma\) is the fraction of binding sites filled on the hemoglobin protein (also often represented as \(\theta\)), \([L]\) is the concentration of the ligand (in this case, oxygen) and \(K\) is the dissociation constant. The variable \(n\) is the Hill coefficient, which can be used to quantify the cooperativity of the reaction. If \(n = 1\), then there is no cooperativity present, and the equation is equal to the model we presented above [3].

The Hill equation fits experimental data nicely, but it brings up some interesting questions. For example, the Hill equation assumes that four oxygen molecules are simultaneously binding with the hemoglobin protein, but that’s a pretty unreasonable assumption [1]. So what, exactly, does the cooperativity look like? How is the binding of multiple oxygen molecules to the hemoglobin protein making the later binding events “easier”?

What Does Cooperativity Actually Look Like?

Whitty suggests that there are two different phenomena that drive cooperativity: allostery and configurational pre-organization [2]. Let’s consider each in turn. Allosteric binding refers to a situation where the binding of an oxygen molecule to one site on a hemoglobin protein will change the binding affinity for another oxygen molecule that could bind to another site on the same protein [2]. For this to happen, there needs to be “allosteric communication between binding sites” on the same hemoglobin protein [2]. Typically, scientists describe this communication as a change in the conformation of the protein - essentially, the protein bends or stretches in some way that makes it “easier” for another oxygen molecule to bind to another binding site on the protein [2].

Configurational pre-organization refers instead to a situation where one binding event helps to arrange or organize other binding sites so that they are more likely to see binding events as well [2]. For example, if we return to the example of protein folding, then one local binding event reduces the number of available degrees of freedom in the protein, and makes other binding events more likely. The first binding event has organized the protein structure so that other specific binding configurations are now more likely to occur. Other terms used to describe this phenomenon include avidity or enforced proximity [1,2].

Now that we have these two ideas in hand, let’s return to this problem that the Hill equation is assuming that four oxygen molecules simultaneously bind with the hemoglobin protein and look at models which consider more realistic scenarios.

Other Models of Cooperativity

Naturally, one might imagine that instead of having four oxygen molecules miraculously strike the same hemoglobin protein at the same time, we could consider what would happen if four oxygen molecules bound with the protein sequentially. This would give rise to the Adair model for cooperativity which can be written as [1]:

\[\gamma = \frac{\frac{1}{4} a_1 x + \frac{1}{2} a_2 x^2 + \frac{3}{4} a_3 x^3 + a_4 x^4} {1 + a_1 x + a_2 x^2 + a_3 x^3 + a_4 x^4}\]Where the coefficients \(a_1\) to \(a_4\) are functions of the equilibrium constants for each of the four oxygen molecules [1]. This model can be fit to experimental data very well, and to do so, we need to assume that cooperativity exists by making the latter binding events more favorable than the earlier ones [1].

Okay, but how, specifically, would the earlier oxygen binding events make the later ones more energetically favorable? The Koshland-Nemethy-Filmer (KNF) model suggests that when the first oxygen binds to the hemoglobin, then the other three binding sites are affected allosterically to increase their affinity for binding to oxygen molecules [1]. Remember earlier that we defined allostery as bending the protein molecule in some way.

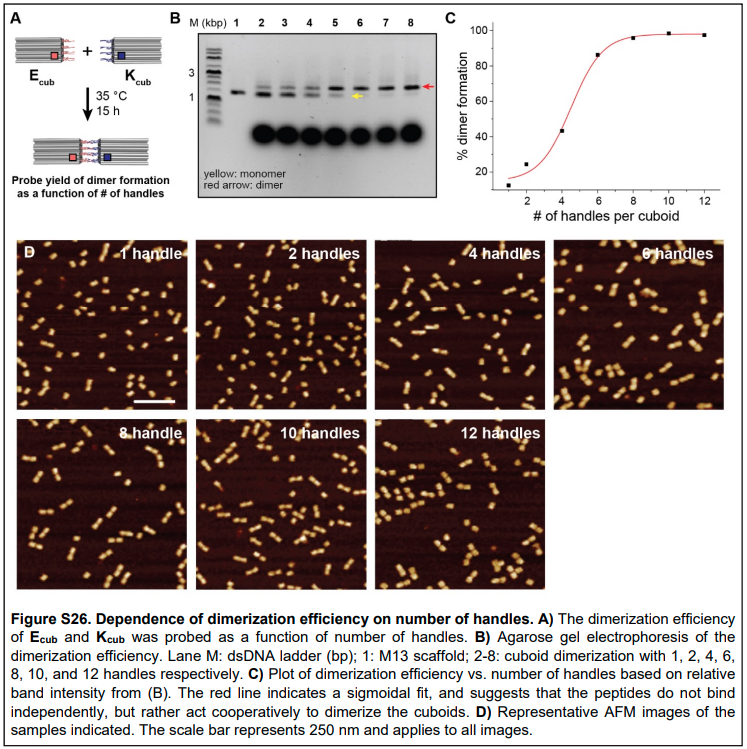

Why couldn’t configurational pre-organization (or avidity) also be used to explain the increased affinity for oxygen in later binding events? Ferrell argues that since avidity only affects the complex itself (i.e. just the binding events on the same protein), then we will see a Langmuir/Michaelian-type binding curve instead of a sigmoid to describe the cooperativity effects [1]. But I would counter that there is evidence from the DNA nanotechnology literature that indicates that adding more binding sites to the same structure increases the cooperativity in a sigmoidal fashion [8], as shown in Figure 2. This bears thinking about in more detail…

Figure 2 - Source [8]

There is an alternative paradigm that considers cooperativity, not as a sequential process, but as a process that switches between two states. The Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) model assumes that when the first oxygen binds to the hemoglobin, it does not affect the binding affinity of the other three binding sites on the protein. Instead, they argue, the protein has two conformations - a “tense” and a “relaxed” state. If the protein has no oxygen bound to it, then it is in the relaxed state, and if one or more oxygens are bound to the protein, then it is in the tense state. More specifically, the hemoglobin protein is made up of four globin subunits that each bind to one oxygen - these are the binding sites of the protein. We assume that if one of these globins is bound to an oxygen, it changes the conformation of the entire protein. Ferrell compares this to a pile of sleeping kittens - if one of the kittens shifts, all of them will have to adjust themselves slightly [1].

Now that we have these tense and relaxed states, the MWC model assumes that the relaxed state binds more favorably to the oxygen molecules (this is the opposite of how we considered the binding affinity in our earlier discussions). In this case, if we consider the system at equilibrium, then there will be more hemoglobins in the relaxed state than in the tense state because the relaxed state is more energetically favorable. We can model this equilibrium state as follows [1]:

\[\gamma = \frac{ K_2 \frac{x}{K_1} \left( 1 + \frac{x}{K_1}\right)^3 + \frac{x}{K_3} \left( 1 + \frac{x}{K_3}\right)^3} { K_2 \left(1 + \frac{x}{K_1}\right)^4 + \left(1 + \frac{x}{K_3} \right)^4}\]Where \(K_1, K_2, K_3\) are the equilibrium constants for binding oxygen to tense hemoglobins, for binding oxygen to relaxed hemoglobins and the flipping of hemoglobin between relaxed and tense conformations. This model can also fit the sigmoidal experimental data very well [1].

At first glance, the MWC model does not seem to take cooperativity into account, since we assume that the binding event of oxygen to one globin has no effect on the affinity of the other globins in the protein. But the fact that the entire hemoglobin protein can flip from the tense to relaxed states is important here. In particular, when an oxygen binds to the protein, it makes it more likely that the protein will flip to the tense state - once in the tense state, it is more likely that the next oxygen will bind to the molecule. So, indirectly, the first oxygen binding event makes subsequent ones more likely because it increases the likelihood that the protein will be in the tense state [1].

The Energy Perspective

It is helpful to consider cooperativity in terms of thermodynamic energy as well. Recall that we said that allosteric cooperativity involves bending the protein so that subsequent ligands can bind to it more easily. This requires moving the protein to a higher energy than its ground state - the energy to do this comes from the binding event itself [2]. In generally, Whitty argues that cooperativity is a way to exchange excess energy released on binding for greater configurational organization [2].

Negative Cooperativity

I wanted to mention very briefly before we close that cooperativity can be negative as well as positive. For example, the first binding event can reduce the affinity of a protein to bind to other ligands [1,3]. This can be captured by a KNF model, but not by an MWC model [1].

Final Thoughts

Cooperativity is an amazing, and essential, mechanism for binding molecules together in biological processes. There are many different models in existence that can capture and provide probable explanations for what mechanisms are driving cooperativity. But there are lots of opportunities, too, for greater investigation of cooperativity and how it plays out in different biological systems. For example, Ferrell argues that studying systems that can be monitored in real time to study how the cooperativity among multiple binding sites affects the process is very valuable in verifying or developing new models for cooperativity mechanisms. I am excited to see how we can do this in DNA nanotechnology to better understand how to leverage cooperativity in the formation of multimeric structures!

Footnotes

*1 A ligand in biochemistry refers to something that binds with a biomolecule to perform some biological function [4]. Often, the “something” is a molecule that binds to a specific site on a target protein to send some kind of signal to the rest of the system [4]. The term means something slightly different in chemistry, where a ligand is either an ion or a molecule that binds to a central metal atom to create a coordination complex [5]. So in both cases, the idea is generally the same - the ligand is something that binds with something else to form a larger structure.

References

[1] Ferrell, J. E. (2009). Q&A: Cooperativity. Journal of Biology, 8(6), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/jbiol157

[2] Whitty, A. (2008). Cooperativity and biological complexity. Nature Chemical Biology, 4(8), 435–439. https://doi.org/10.1038/NCHEMBIO0808-435

[3] “Cooperativity.” Structural Biochemistry wikibook. https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Structural_Biochemistry/Protein_function/Binding_Sites/Cooperativity Visited 28 May 2022.

[4] “Ligand (biochemistry).” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ligand_(biochemistry) Visited 28 May 2022.

[5] “Ligand.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ligand Visited 28 May 2022.

[6] “Levinthal’s paradox.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Levinthal%27s_paradox Visited 28 May 2022.

[7] “Langmuir adsorption model.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Langmuir_adsorption_model Visited 28 May 2022.

[8] Buchberger, A., Simmons, C. R., Fahmi, N. E., Freeman, R., & Stephanopoulos, N. (2020). Hierarchical Assembly of Nucleic Acid/Coiled-Coil Peptide Nanostructures. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 142(3), 1406–1416. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.9b11158