The Structure of DNA

Word Count: 499

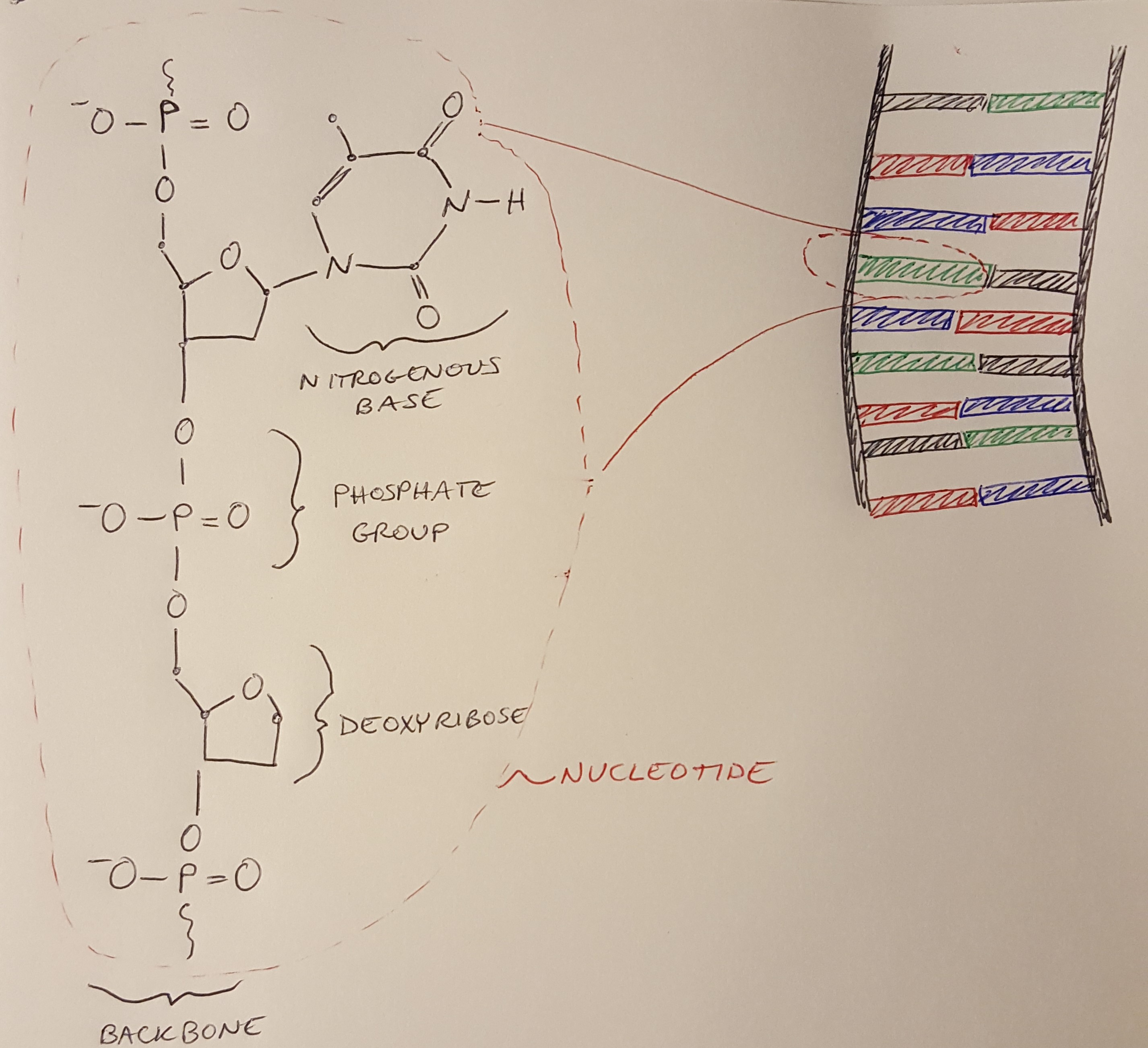

In my last post, we learned about the structure of the human genome, beginning with DNA. Now let’s explore the structure of DNA itself. To do that, we are going to look at some diagrams of the chemistry of DNA, starting with Figure 1 below. Previously, we described DNA as a ladder, where each rung of the ladder is a nucleotide. In Figure 1 we see a chemical diagram of a single nucleotide and how it would fit into the ladder of DNA [1]. The nucleotide contains the backbone on the outside of the ladder, and the nitrogenous bases which form the rungs [1].

Figure 1

Let’s consider the backbone first. The backbone is an alternating sequence of a sugar and a phosphate group. The sugar is called deoxyribose - hence the name Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid. And the “acid” in DNA comes from the phosphate group - we’ll discuss this more soon. Lastly, the nitrogenous base can be one of four different bases: adenine, cytosine, guanine or thymine [1]. In Figure 1 I have drawn thymine. Let’s dig a little deeper into each of these structures.

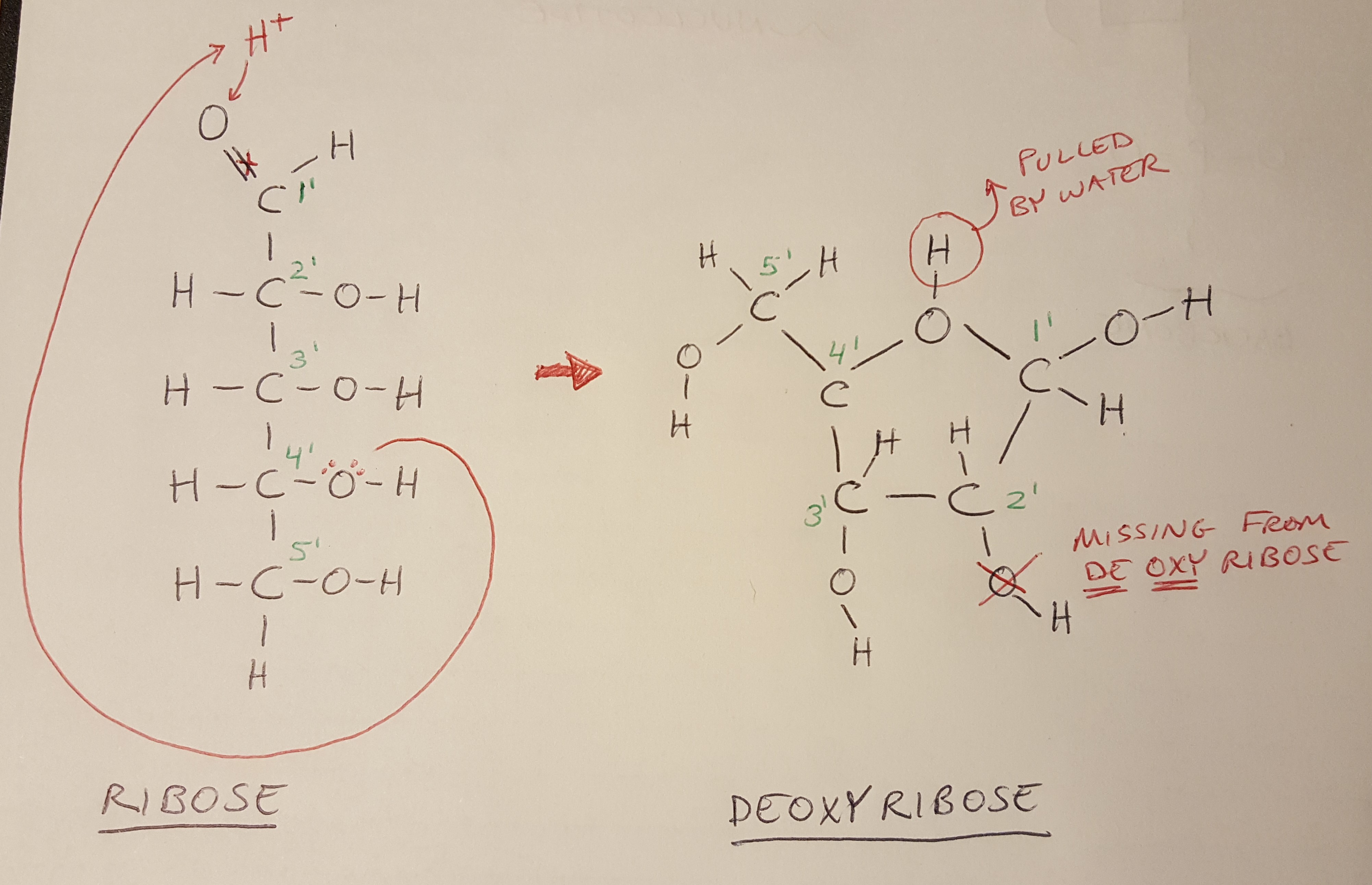

Deoxyribose is formed from a straight chain of carbons called ribose (this is shown in Figure 2). Notice that the carbons in the chain are numbered from 1’ (we read this as “one prime”) to 5’ - the numbering sequence is going to be important later. In the original ribose molecule, one of the bonds in the double bond between the 1’ carbon and the oxygen is broken, so that the oxygen can grab a proton (i.e. the H+ atom drawn in red). This proton is attracted to the relatively negative charge of the lone pairs of electrons on the oxygen atom connected to the 4’ carbon (see the long red arrow). The chain bends all the way around so that the 4’ oxygen can bond with the 1’ hydrogen. This forms the ring structure of deoxyribose. To complete the structure of deoxyribose, the proton that the oxygen wanted to grab is ultimately pulled away by the surrounding water, and the oxygen atom on the 2’ carbon is also missing from the structure, making this DEOXYribose [1].

Figure 2

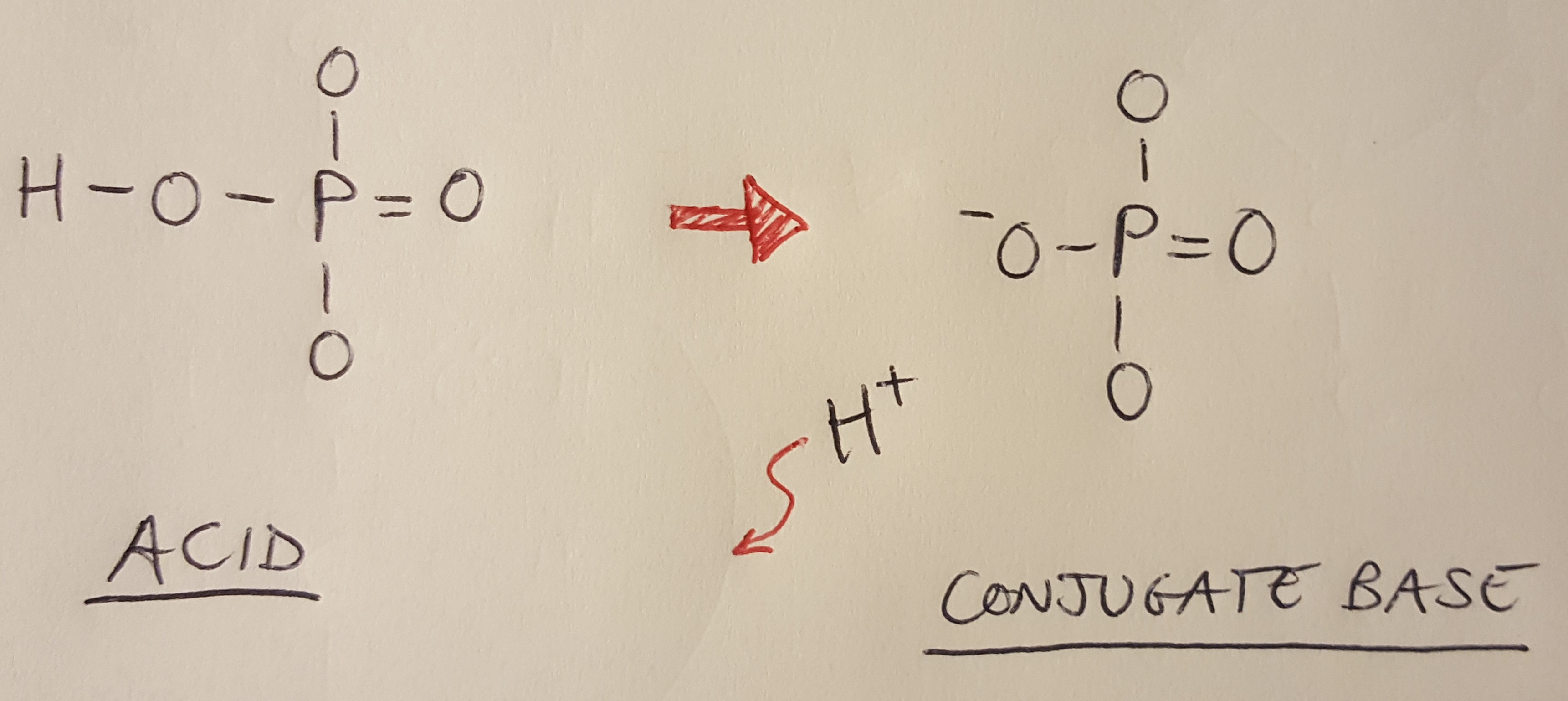

Let’s move on to the phosphate group. Notice that it is drawn with a negatively charged oxygen atom on the left hand side. This oxygen atom has lost a proton to the surrounding water. By definition, acids donate protons in solution, so the loss of this proton makes this entire molecule an acid [2]. We typically draw DNA as showing the phosphate group with the proton already gone - in other words, we show the conjugate base [1].

Figure 3

Finally, the nitrogenous bases are perhaps the most interesting part about the DNA molecule, so they deserve their own post, where I will explain how base pairing works for DNA and why we say that it has an “anti-parallel” structure. In the meantime, I will challenge you to figure out why the numbering of the carbons in ribose is important to describing DNA…

References

[1] Khan Academy. “Molecular structure of DNA.” https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/dna-as-the-genetic-material/structure-of-dna/v/molecular-structure-of-dna Visited 05/13/2019.

[2] ThoughtCo. “Acid Definition and Examples.” https://www.thoughtco.com/definition-of-acid-and-examples-604358 Visited 5/22/2019.