Modeling DNA

Recently I realized that I do not know how the DNA research field models the structural deformation properties of DNA and its various constructs. This is something that I am going to need to learn in much more detail, but as a first exploration of the field (before my research qualifying exam tomorrow), I wanted to write a brief summary of what I have learned so far. Please take this post with a grain of salt and know that I have a lot more to learn on this topic!

Why is it difficult to model DNA in the first place? Why can’t we simply call it a rigid beam and apply all of the beam bending equations that we learned in sophomore year in mechanical engineering? The problem is that DNA acts much more like a soft polymer than like a rigid material like steel or aluminum. There are two modes of deformation that we are going to be thinking about here: (1) axial (tension) and (2) transverse (bending) [1].

Let’s talk about some of the key material properties of DNA that we need to know for this discussion. DNA is a double-stranded helix with a diameter of 2.5nm. Each base pair is spaced out 0.34nm from the next. The helix completes a full revolution every 10.5 base pairs [4]. The double helix has a Young’s modulus similar to spaghetti, approximately 10^8 J/m3 [2]. And finally, DNA has a persistence length of 53 +/- 2nm [1]. But what is the persistence length?

Most engineers do not encounter the persistence length as a material property during their careers. It is used more to describe polymers and filaments, especially in the biological sciences. There are several definitions for the persistence length. One definition is that it is the distance along the filament that you must travel from the filament’s origin before the deformation of the filament is no longer correlated to the orientation of the filament’s origin. Another definition of the persistence length of a filament states that the longer a filament’s persistence length is, the straighter a section of that filament will appear to the observer [1]. The key thing to remember here is that the persistence length is correlated to the bending rigidity of the material [1].

My ultimate goal in writing this post is to identify the models that researchers agree are the best for representing the stiffness of DNA. But before we get there, I think we should talk about how different factors (temperature, entropy and energy) affect the bending rigidity of DNA. Once we have some intuition for how DNA behaves, I will discuss the relative merits of the freely-jointed chain and worm-like chain models and why some scientists prefer the worm-like chain model for understanding DNA’s material properties.

Bending Rigidity and Temperature

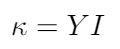

Let’s start by defining the flexural rigidity of DNA in terms of temperature, because I think this is the most intuitive way of understanding DNA’s material properties. We can define the flexural rigidity of DNA (kappa) as the product of the Young’s modulus of DNA and its second moment area of inertia, as shown in the equation below [1]:

This should feel familiar to most engineers; the equation tells us that the deformation of DNA depends on its elasticity (the Young’s modulus) and the size of the DNA’s structural cross section (second moment area of inertia).

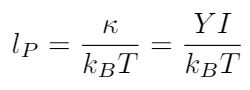

We can use the bending rigidity to write an expression for the persistence length of DNA. Intuitively I think it makes sense that the persistence length of DNA would depend on its bending rigidity - if DNA was very flexible, the persistence length should be shorter (i.e. the DNA strand should curl more) than if the DNA was very stiff, and the strand curled less [1]. But the persistence length does not depend only on bending rigidity; in this expression, we will also need to account for the temperature of the strand. Why does this make sense?

If a polymer strand (I imagine something like rubber or a soft plastic when I think about this) is very cold, it feels rigid. It is difficult to bend or deform. But if you heat up that polymer strand, it becomes more malleable, and it is easier to bend. The same is true for DNA: at lower temperatures, it is more stiff, and consequently its persistence length is longer [1]. At higher temperatures, the DNA is more flexible, and its persistence length gets shorter [1].

Now let me add an idea that was new for me as a mechanical engineer - even at thermal equilibrium, when the DNA strand has the same temperature as its surroundings, it is constantly exchanging thermal energy with the surrounding fluid [1]. The DNA strand’s thermal energy fluctuates, and we can say that it fluctuates on a time scale defined by kB*T, where kB is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature of the environment [1]. This explains why you can look at a strand of DNA under a microscope and see it constantly changing shape in the fluid, even though there is no fluid flow and minimal thermal variation in the environment; these constant fluctuations are resulting in shape changes along the length of the filament [1]. This gives us the expression for the persistence length’s dependence on temperature, and now we can write an equation for the persistence length of DNA [1]:

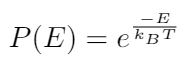

Before we move on to talking about entropy, let me introduce one more topic that will be useful when we think about entropy. We can say that there is a probability that the DNA strand will assume a specific configuration. Think about an elastic polymer strand - there are many different contorted shapes that it can take, but only a few configurations where the strand is mostly straight [1]. So the probability that a strand appears contorted is much higher than the probability that the strand appears straight [1]. We can use the bending energy and the temperature of the filament to write the probability that the filament will assume a particular shape as follows [1]:

Where E is the bending energy, and kB and T we have already defined. This expression for the probability tells us that the larger the bending energy required to deform the polymer strand, the less likely it is for the polymer to take that shape [1]. Similarly, it also shows that higher temperatures make it more likely that the filament will assume a particular configuration [1].

Bending Rigidity and Entropy

So now we have seen that the likelihood that a filament takes on a convoluted shape is greater than the probability that the filament is straight, because there are more variations of convoluted shapes available [1]. If we were to start stretching this filament, we would cause it to straighten out. We would also reduce the number of available contorted configurations, and we would increase the probability that the filament would appear straight [1]. In other words, we are decreasing the system’s entropy, because we are making it more ordered [1]. Nature does not naturally reduce its entropy, so we must apply a force to straighten out this filament [1].

So now we have several explanations for why DNA resists bending on the microscale.

(1) The DNA strand has a bending rigidity material property that describes its resistance to bending [1]. This is the traditional engineering definition.

(2) At warmer temperatures, the DNA strand’s energy is fluctuating quickly and it is assuming many different configurations [1]. To oppose this trend, we must apply a force to straighten out the strand. Conversely, at lower temperatures, the DNA strand’s molecules have found the most energetically favorable positioning, and it requires a force to be applied to push these molecules into a different configuration [1].

(3) Any strand will naturally tend to increase its entropy by assuming a contorted shape [1]. To oppose this, we must apply a force to the strand to achieve a more organized, straight configuration [1].

Modeling DNA Strands

Now that we have some intuition for the variables affecting the behavior of DNA, let’s examine some different approaches for modeling its deformation characteristics.

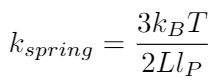

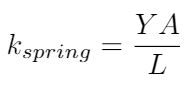

The simplest approach is to use Hooke’s model, which is valid for small extensions of the polymer strand [1]. We can write the spring constant for the DNA strand in two different ways using different material properties [1]:

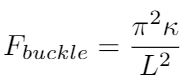

Hooke’s model is an acceptable model because DNA strands can experience axial deformations in tension. However, it is not clear to me that we can always model DNA as experiencing compression - it is very flexible, so the buckling force may be so small that DNA will never experience compression, it will always buckle first [1]. We can write the buckling force as a function of the DNA’s bending rigidity [1]:

Where L is the length of the entire strand. Boal argues that we can model microtubules (which are much stiffer than DNA) as tension-compression couplets, because it has some resistance to buckling forces [1]. But he suggests that DNA may be so flexible that we can only represent it as a tension-bearing element, in which case we cannot think about DNA bending like a beam, because none of the DNA strand’s fibers will experience compression [1].

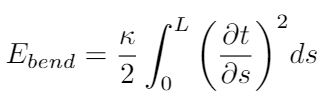

This brings us to look for other ways to characterize the way that DNA strands bend. One way to do this is to model DNA as a series of freely-jointed rigid segments. Each segment can move independently of the next, but each segment itself is rigid [1],[3]. Again, Boal argues that this is not the preferred model for DNA because DNA is not very rigid [1]. Instead, he (as well as some other literature I’ve encountered) prefers to use the worm-like chain model [1],[5]. This model represents the DNA strand as a flexible, continuous and isotropic rod [1]. It uses the Kratky-Porod model to calculate the energy required to bend such a rod, as shown in the equation below [1]:

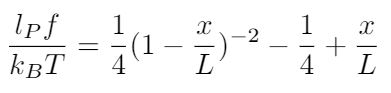

Where s is the distance along the rod and L is the rod’s total length. I think this expression could be interesting to use in an energy-based model of DNA and how it deforms under load, and is worth more investigation. I also know that Marko and Siggia established a formula for the persistence length of DNA based on experimental data and this model, as shown below [1],[5]:

Where f is the applied force.

Conclusion

I still have more reading and understanding to do. But right now, I think some of my key takeaways are that DNA probably should not be modeled as a beam the way mechanical engineers like to do. DNA probably cannot support compressive forces, so we need to find ways to model its behavior as a tension-bearing element only. I think I need to learn more about the worm-like chain model, because that appears to be a preferred approach to representing the behavior of DNA strands with energy and applied forces.

References

[1] Boal, David H. Mechanics of the Cell. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

[2] Sheetz, M. and Yu, H. The Cell as a Machine. Cambridge University Press, 2018. https://books.google.com/books?id=WMhJDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA215&lpg=PA215&dq=young%27s+modulus+of+dna+in+J/m3&source=bl&ots=wCnviVfJPs&sig=ACfU3U22-TdfwMhB5kpeGqnwUw8ZcH1XVw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi_g_m5x7XkAhVqQt8KHTUnD8AQ6AEwBHoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=young's%20modulus%20of%20dna%20in%20J%2Fm3&f=false Visited 09/03/2019.

[3] “Worm-like chain.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Worm-like_chain Visited 09/03/2019.

[4] “Nucleic acid double helix.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nucleic_acid_double_helix Visited 09/04/2019.

[5] J. F. Marko and E. D. Siggia, “Stretching DNA,” Macromolecules, vol. 28, no. 26, pp. 8759–8770, Dec. 1995.