Docker Basics

In this post we are going to introduce a useful tool called Docker containers. I came across these recently when I decided to finally move my deep learning model off Google Colab and onto a computer equipped with GPUs.*1 The Biorobotics lab uses Docker containers so that every lab member can run their own code inside a confined space on a shared workstation without affecting anybody else’s work. In this post I’m going to explain the motivation for using Docker containers, present the basic underlying principles for how they are set up, and provide some useful commands for using them. I may write a follow-up post focused on best practices, as well.

What are Docker Containers and Why Use Them?

I have heard cool computer scientists call Docker containers “sandboxes,” because they give you a place to play around with code without fear of affecting anything outside the container [1]. They are similar to virtual environments in Python or virtual machines in that they are a dedicated ecosystem inside your computer with their own operating system, packages and scripts installed [1]. You can set up your Docker container to run exactly the right version of Python for your application, for example, so that your application will always run no matter what version of Python is running on the workstation hosting your Docker container [1].

The other beautiful thing about Docker containers is that they don’t affect code located elsewhere on the host computer. This is great in a research lab where the computer itself is a shared resource, and I may need to use different versions of Python or Tensorflow than other people in the lab. In this scenario, I can set up my Docker container to match my application requirements without messing up anybody else’s setup [1]. This is especially comforting if you are, like me, new to running deep learning models and you’re a little afraid that you’ll destroy other people’s codebases. It’s hard to make friends with people after irrevocably destroying their thesis project.

To get a little more technical, we can say that Docker containers are an open-source tool that allows you to package your application inside a “standardized unit,” along with all of the application’s dependencies [1]. To the best of my knowledge, Docker containers are primarily run in Linux; I’m not sure if they can be used on other operating systems [1]. The difference between a Docker container and a virtual machine is that the Docker container is designed to be more lightweight [1]. I don’t understand exactly how the Docker engineers were able to do this, but they were able to design containers that use the host computer’s compute resources very efficiently [1]. This is good for you because it means you get a larger share of the host computer’s resources for your application, and you are spending less of it on the infrastructure of your sandbox [1].

Underlying Principles of Docker Containers

In this section I want to introduce some of the terminology for talking about Docker containers. (I always find that understanding technical things gets a lot easier once you have mastered the vocabulary.) We start with the Docker image, which is the “blueprint” of the Docker container [1]. That is, the Docker image is the source code which you can download and compile to run a Docker container [1]. You can store Docker images in your Docker repository so that you can put them on any computer [1]. As you might imagine, this is especially useful when you have a lab with multiple workstations available for use and you want to be able to switch easily between using different machines based on their availability.

Now that we have downloaded a Docker image, we create a Docker container from that image (i.e. an instance of the image on your host machine). There is a Docker daemon running in the background on the host machine which is always managing the building, running and distribution of all the Docker containers on that machine [1]. The daemon is working with the host machine’s operating system to allocate resources [1]. The user (you) is interacting with the daemon through the Docker client, which is just a command line tool that lets you manage your containers [1]. (Apparently there is also a GUI available if you prefer to use that [1].)

Let’s talk a little more about images for a minute. There are two kinds of images: base and child images [1]. Base images do not have parent images - they usually contain fundamental codebases like operating systems or Python 3.6.9 [1]. Child images, in contrast, build on top of base images, adding more functionality for your specific application [1]. For example, I am currently building a child image that draws on the Python 3.6.9 base image - this ensures I have all the functionality of this version of Python which I can use in my particular deep learning model. You could also say that my image is a user image because I wrote it myself [1]. Conversely, official images are ones that are maintained and supported by engineers at Docker, and they usually consist of images for operating systems or coding languages [1].

Workflow

So now that we have some familiarity with the Docker container paradigm, let’s walk through how we might use one in practice. Srivastav provides some excellent in-depth examples in his tutorial [1], and I will only give a brief overview here. In short, the steps to creating and using a Docker image are as follows:

- Create an image by preparing your application code and writing a Dockerfile.

- Build the Docker image.

- Run the Docker container based on that image.

- Commit the image to Docker Hub.

Create an Image

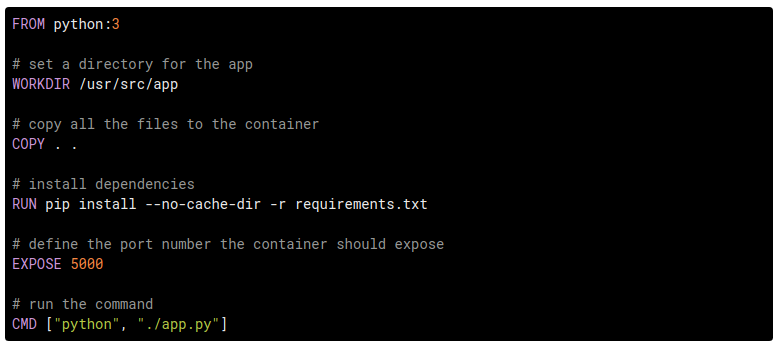

Let’s say that I want to set up a Docker image for a particular deep learning model that I have written. I already have a Github repository with the deep learning model codebase. The first thing I need to do is create a Dockerfile that defines what commands the daemon will call while building my Docker image [1]. The Dockerfile is similar to a bash script in Linux which automates the image creation process by telling the daemon what base image to use, what packages to install and what scripts to run [1]. In my next post I’m going to go into more detail about some best practices for writing Dockerfiles, because there are some subtleties to writing them well. But a simple Dockerfile is shown below [1].

Figure 1 - Source: [1]

The FROM command indicates what the base image is for this Docker image - in this example, the base image is Python 3. We choose a directory to locate the application inside the image using WORKDIR. Then we COPY all the files and install the application’s dependencies using RUN. This particular example creates a simple website so we need to EXPOSE a port for the webpage. Finally, we run the primary script for the application with the CMD command [1].

Build an Image

Once you have written the Dockerfile, you are ready to build the Docker image. We use this command [1]:

docker build -t username/image-name .

Don’t forget to put the full stop at the end. The “-t” flag just adds a tag to the Docker image with your username/image-name. Notice that it is best practice to name all the images that you create following this format of using your Docker username and then the image name after a forward slash [1]. This build command will run through all the commands in the Dockerfile, and may take a while the first time you run this command because you may need to install a lot of packages in support of your application. (There are ways to cache your packages when your dependencies don’t change much from build to build - we’ll talk about that in another post.)

Run the Container

Once the Docker daemon has successfully built the image, you can run it using [1]:

docker run username/image-name

This will open your Docker container and run through the code specified in the Dockerfile. If you use the Terminal command as listed here, the Docker container will close again (but not delete itself) when it’s done. There are additional flags you can add to open a container and run commands inside the container, for example:

docker run -it container-name sh

The “-it” flag provides an interactive TeleTYpe (tty) interface to the container, which just looks like inputting commands to the Terminal. You can also use:

docker run –rm –interactive –tty container-name

Commit to Docker Hub

Similar to Github, Docker hosts a repository service called the Docker Hub that allows you to publish your images [1]. It’s free to create an account and host your images on the Docker Hub. Use this command to log in [1]:

docker login

And this command to publish your image [1]:

docker push username/image-name

When you want to pull your image on a new workstation, use this command [1]:

docker pull username/image-name

There you go! Now you have a way to build your own images and store them in a repository so that you can access them from any workstation. In the next section we’ll go over a couple more useful commands for working with Docker containers.

Other Useful Commands

You can see all of the Docker containers that you have run using:

docker ps -a

This command allows you to see the containers, even if you have stopped running them. Note that after a container finishes running, they are not completely removed from your hard disk and can pile up and consume disk space if you don’t delete them [1]. To remove containers that you don’t need any more, you can either remove the specific container with [1]:

docker rm container-ID

Or you can use the prune function [1]:

docker container prune

Remember to use these commands occasionally, especially when using a shared workstation.

You can also see all of your images using [1]:

docker images

So that’s it for this post. I hope it was a useful introduction to Docker containers. I hope to write a follow-on post soon with some more best practices for building Dockerfiles and other activities.

Footnotes:

*1 Don’t get me wrong, I love Google Colab and how easy it is to use, but the conventional wisdom is that once you get your model working, you need to move it to a workstation with a dedicated GPU. The problem with staying on Google Colab as you train your model for many epochs is that you can be kicked off the server’s GPUs at any time, which can seriously interrupt your run or cause it to fail completely. This was happening to me as I was preparing a short paper submission and it made me very nervous. So now I’m investing the time in learning how to use Docker containers so it doesn’t happen again!

References

[1] Srivastav, P. “Docker for Beginners.” https://docker-curriculum.com/ Visited 19 Oct 2020.