Review of "Entity Abstraction", Part 3

We have been discussing a recent paper by Veerapaneni et al. that presents a novel way of teaching a computer to think and reason by representing its environments as entities that are related to each other by some laws [1]. In this final post summarizing this paper, I want to explain (at a high level) how the OP3 learner is able to connect objects that it sees in video frames to entities in its latent space [1]. We concluded the previous post by saying that the method OP3 uses is called “amortized interactive inference” [1]. Let’s find out what that means.

This part of the learner is binding the physical objects in the true environment, h*, to the entity states, H, in the learner’s latent space [1]. Veerapaneni et al. frame this problem in an interesting way; they say that we can find this binding information by trying to infer the parameters for the distribution P(H given x, a), the posterior distribution of entity states given a sequence of interactions [1]. That is, the paper binds the objects to the entities based on how well the resulting predictions of the entity states (given some observations and actions) match reality [1]. Specifically, OP3 is learning this binding information when it maximizes the ELBO, as we saw in the previous post on this paper [1].

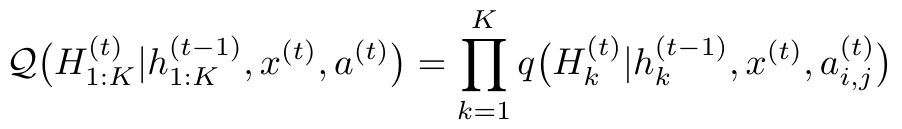

Another way to say this is to say that the ELBO is also enabling OP3 to learn an approximation for the recognition model, Q, which contains this binding information. We can write the recognition model as the product of recognition distributions, q, for each individual entity [1]:

Equation 1 - Source: Equation 4 in [1]

But how do we calculate this model? That’s the really cool part. Veerapaneni et al. use an “interactive inference approach” which basically means that they are able to learn to recognize different objects as entities based not only on their observations of the scene, but also on the actions taken by the learner inside the scene [1]. That is, the learner is actively interacting with the environment and learning from those interactions - it’s basically a baby playing with blocks to learn how to build towers! We say that this process is “amortized” because it happens over time, because the learner continues to refine its recognition (or disambiguation) of different objects over multiple time steps [1].

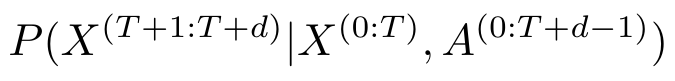

Equation 2 - Source: [1]

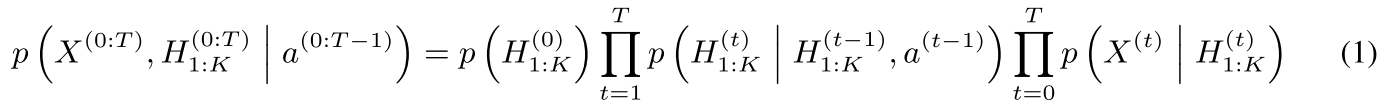

The process of interactively inferring begins with an initial guess about the posterior parameters, lambda [1]. When we say “posterior,” I think we mean the posterior predictive distribution, given as Equation 2 [1]. The learner refines this guess by computing gradients that describe how well the generative model predicts the next observation [1]. We saw the generative model in my first post on this topic, and it is given in Equation 3 [1].

Equation 3 - Source: [1]

Sometimes, the location and color of each object are different enough that the learner can quickly distinguish between them [1]. But if not, the learner is able to use a filtering approach to incorporate the actions and subsequent observations to improve its guess about which object should be bound to which entity in the models [1].

The OP3 approach learns at three different timescales - first, the parameters, lambda, are learned over multiple iterations inside a single timestep [1]. Secondly, the parameters are also updated across multiple time steps for a given scene, and thirdly, the neural networks that compute the recognition, dynamics and observations models learn over multiple scenes [1].

The rest of the paper presents the researchers’ experiments and results. I will not present them here because I was more interested in how they built their learner, but I would highly recommend looking at their paper on ArXiv and their corresponding website.

I hope this explanation has been useful to you. If you find any mistakes or misconceptions, please let me know. I am by no means an expert in this topic so it is highly likely that I have made mistakes in these posts.

References:

[1] R. Veerapaneni et al., “Entity Abstraction in Visual Model-Based Reinforcement Learning,” Oct. 2019. ArXiv ID: 1910.12827 https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.12827