Understanding Message Passing in GNNs

I have written about graph neural networks (GNNs) a lot, but one thing I am still trying to understand is how message passing works when you add neural networks to the mix. Message passing, put simply, refers to sharing information between nodes in a graph along the edges that connect them. I first encountered it in discussions about variable elimination for performing inference on a probabilistic graphical model (PGM) - we will demystify that sentence below - but I still wanted to make the connection for myself between doing this analytically on a small graph to doing it computationally with a much larger graph and using neural networks. Let’s dive in!

Graphical Models Can Only Do 2 Things

Well, okay, I mean, maybe they can do lots of things but we can broadly categorize the tasks that you can perform with graphical models into two tasks: learning and inference. Learning refers to finding the graphical model, \(M\), given some data, \(\mathcal{D}\). Conversely, inference refers to calculating a probability \(P_M(X | Y)\) using the model \(M\) [2]. Message passing, the star of today’s blog post, emerges as a technique for performing inference.

Let’s pause and review the basics of probability and what kinds of probabilistic inference we can perform. There are two forms that we commonly try to solve with PGMs: marginal inference and maximum a posteriori (MAP) inference [3]. Marginal probability asks what the probability of observing a single random variable is, given any outcome for the other random variables. In other words, we sum over all of the other random variables in the model except for the ones we’re interested in.*1 We can write this as [3]:

\[P(y = 1) = \sum_{x_1} \sum_{x_2} … \sum_{x_n} p(y = 1, x_1, x_2, …, x_n)\]Alternatively, the MAP inference asks what is the most likely value for all the random variables in our model [3]:

\[\max_{x_1, …, x_n} p(y = 1, x_1, … , x_n)\]So inference involves calculating some probability given the model that we have. As we’ll see below, this is very straightforward if the model is small - in this case, we can compute the exact inference value for our model. However, if the model is much larger and more complex, then we may find that calculating either of these forms of inference becomes intractable. In that case, we must turn to using various algorithms for approximate inference since the exact value is NP-hard [3]. In this post, we’ll confine ourselves to discussing exact inference because that is all we need to understand to get to message passing, but I wanted to mention this here so that we were aware there are other approaches for when graphs get larger.

Variable Elimination as Inference

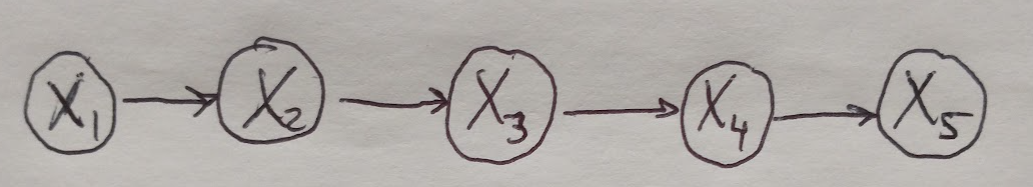

Here we will see how we can perform exact inference by computing the marginal probability for a small directed chain graph as shown in Figure 1. Our graph represents the joint probability over all the random variables in all of the nodes of the graph. We will see that we can take advantage of the graphical structure of this model to make computing the marginal probability very efficient.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Note that the meaning of these factors varies slightly depending on which type of graphical model you are working with. For directed graphs, the factors are conditional probabilities with respect to the node’s parents, i.e. \(\{ P(X_i \text{ given } X_{PA_i}) \}\). For undirected graphs, the factors are called clique potentials and are written as \(\phi_c (X_c)\). Clique potentials become probabilities after they are normalized [1]. If we wanted to compute the marginal probability of \(P(X_5)\), we would sum over all of the other variables, like so [2]:

\[P(X_5) = \sum_{X_1} \sum_{X_2} \sum_{X_3} \sum_{X_4} P(X_1, X_2, X_3, X_4, X_5)\]The computational cost of doing this naively (i.e. just by summing over all of the other random variables in the graph) is \(\mathcal{O}(k^n)\), where \(k\) is the number of possible values of each variable, and \(n\) is the number of random variables [2,3]. The reason why variable elimination is so powerful is that it greatly speeds up the computation of this marginal probability. Graphical models are computationally efficient because they allow us to write all of the possible probabilities more compactly than in a tabular format. However, there is a limitation to this: when we need to sum up (or marginalize) over certain random variables in the joint distribution, that can still be prohibitively expensive even though we are working with a graphical model that is supposed to be efficient. Variable elimination helps us to speed up the process of marginalizing over random variables in our model by side-stepping the need to compute the sum as written above [1]. We are going to see how this works by leveraging the model that we have (Figure 1) to write the joint probability distribution for this graph as [2]:

\[P(X_1, X_2, X_3, X_4, X_5) = P(X_1) P(X_2 | X_1) P(X_3 | X_2) P(X_4 | X_3) P(X_5 | X_4)\]And now we can use this to rewrite the marginal probability for \(P(X_5)\) as [2]:

\[P(X_5) = \sum_{X_1} \sum_{X_2} \sum_{X_3} \sum_{X_4} P(X_1) P(X_2 | X_1) P(X_3 | X_2) P(X_4 | X_3) P(X_5 | X_4)\]Moreover, we can start to move the summations further into the expression, like so [2]:

\[P(X_5) = \sum_{X_4} P(X_5 | X_4) \sum_{X_3} P(X_4 | X_3) \sum_{X_2} P(X_3 | X_2) \sum_{X_1} P(X_1) P(X_2 | X_1)\]Observe that the last term, \(\sum_{X_1} P(X_1) P(X_2 \text{ given } X_1)\), can be simplified to \(P(X_2)\), to give us [2]:

\[P(X_5) = \sum_{X_4} P(X_5 | X_4) \sum_{X_3} P(X_4 | X_3) \sum_{X_2} P(X_3 | X_2) P(X_2)\]We can continue this operation to marginalize out the other probabilities - we also call this eliminating variables, which gives the algorithm its name [2,3]:

\[P(X_5) = \sum_{X_4} P(X_5 | X_4) \sum_{X_3} P(X_4 | X_3) P(X_3)\] \[P(X_5) = \sum_{X_4} P(X_5 | X_4) P(X_4)\]Each time we eliminate a variable, we must perform a computation that is of \(\mathcal{O}(k^2)\) time and then we do this for \(n\) variables, giving us a total computational complexity of just \(\mathcal{O}(nk^2)\), which is clearly less than the naive solution of \(\mathcal{O}(k^n)\) [2,3]. Also, it’s worth mentioning that If you are familiar with computer science, you may have noticed that variable elimination is a form of dynamic programming [2,3].

Now that we have the basic idea of variable elimination, let’s see where the idea of message passing comes into play.

Message Passing

The key insight here is that each variable elimination is a message that is passed from one node to another. Put another way, each time we perform the operation \(P(X_2) = \sum_{X_1} P(X_1) P(X_2 \text{ given } X_1)\), this is a message that is passed from node \(X_1\) to \(X_2\) [3]. Note that the literature often refers to message-passing as belief propagation [2,5]. This insight is valuable because it means that we can reuse messages to perform many different queries very cheaply. For example, if we wanted to compute the marginal probability for a different random variable in the model above, we could rewrite the marginalization process and reuse many of the messages that we had already computed to obtain \(P(X_5)\). This saves us a lot of computation time that we would otherwise have to spend recomputing the same messages [2,5].

This idea unlocks a wide range of algorithms that focus on efficiently organizing the calculations required to marginalize the probability, given that we can reuse messages and that each variable elimination “collapses” part of the graph. I will not go into detail here because these algorithms are also generally for exact inference on small graphs and I’m more concerned here with big graphs and neural networks. But let me just say that generally speaking, all message passing algorithms have to follow the message passing protocol which states that a node can only send a message to its neighbors when it has finished getting all the messages from its other neighbors [2]. This idea of order is critical to message passing algorithms.

Battaglia et al. wrote a beautiful position piece on the value of graphical models in deep learning, and they describe message passing as a means of performing reasoning, much like humans do [6]. They point out that it allows for local information sharing (i.e. between nodes that are connected in the graph) and that it can be, to some extent, parallelized, which makes computations more efficient (this goes back to our mentions of various algorithms that draw on ideas from dynamic programming to perform efficient inference on a graph) [6].

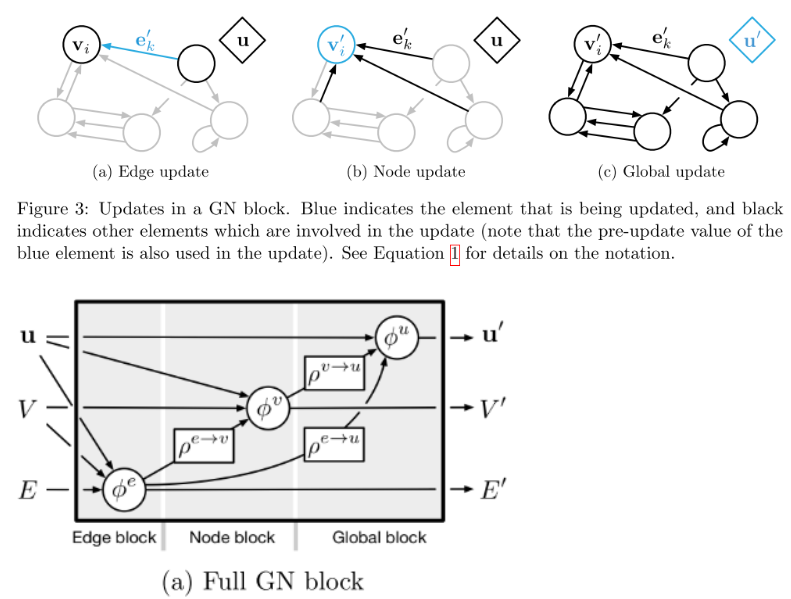

This paper by Battaglia et al. also lays out a general framework for graph net (GN) blocks that ensures basic functions are performed which are common to all graphical frameworks, but also allows for flexibility depending on the application. A GN block includes edges, \(E\) with attributes \(\mathbf{e}\), nodes (or vertices), \(V\) with attributes \(\mathbf{v}\), and global properties, \(\mathbf{u}\). For a directed graph, we also have sender (s) and receiver (r) nodes at the source and sink of a directed edge. Generally, a GN block must perform three update functions (denoted as \(\phi\)) and three aggregation functions, denoted as \(\rho\). These can be written as [6]:

\[\mathbf{e}_k’ = \phi^e(\mathbf{e}_k, \mathbf{v}_{r_k}, \mathbf{v}_{s_k}, \mathbf{u})\] \[\mathbf{v}_i’ = \phi^v (\mathbf{\bar{e}}_i’, \mathbf{v}_i, \mathbf{u})\] \[\mathbf{u}’ = \phi^u (\mathbf{\bar{e}}’, \mathbf{\bar{v}}’, \mathbf{u})\] \[\mathbf{\bar{e}}_i’ = \rho^{e \rightarrow v} (E_i’)\] \[\mathbf{\bar{e}}’ = \rho^{e \rightarrow u} (E’)\] \[\mathbf{\bar{v}}’ = \rho^{v \rightarrow u}(V’)\]And we can also visualize these a couple of different ways as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 - Source [6]

Figure 2 - Source [6]

Now, according to Battaglia et al., authors have implemented forms of GNs that use neural networks to serve as specific functions. For example, Sanchez-Gonzalez et al. [7] used neural networks as the update functions, \(\phi\), and elementwise summation operations for the aggregation functions, \(\rho\) [6]. Battaglia et al. also note that MLPs are well suited to vector-based attributes (\(\mathbf{v}\) and \(\mathbf{e}\)) while CNNs may be a better choice if the attributes are images, highlighting the flexibility of the GN block itself [6].

Why Can I Use a Neural Network for That?

My question, however, is why can we use neural networks to perform message passing, specifically the update functions? To get a better handle on this, I turned to some posts by Daniele Grattarola which were extremely helpful [8,9]. We’ll dive into his explanation for how we do message passing with graphs in a minute, but first let me introduce some new (to me) terminology. Grattarola uses the term reference operator, \(R\) to refer to any matrix that describes the graph and has the same sparsity pattern as the adjacency matrix, \(A\). So, for example, the normalized adjacency matrix and the Laplacian matrix both have the same sparsity pattern (ignoring the diagonal). That means that all three of these matrices have non-zero entries where there are edges in the graph, and zeroes everywhere else (with the exception that some will include ones along the diagonal for self-loops and others omit them) [8].

Reference operators are critical to understanding why neural networks can represent a message passing operation. First, they are, by definition, operators, which means that they transform the graph signal (often this is the node attribute matrix, \(X\) - we saw this terminology in our discussion of graph convolution) and output a new graph signal. Second, when we multiply \(R\) with a graph signal, we are essentially computing the weighted sum of each node’s neighboring nodes - which passes messages between connected nodes [8]. Consider this simple example, where we have a node \(X_1\) connected to nodes \(X_2, X_3, X_4\) (there might be other nodes in the graph but if \(X_1\) is not connected to them then the reference operator would show 0’s everywhere that there could be a connection between \(X_1\) and, say, \(X_5\)). The reference operator is multiplied with the graph signal like so [8]:

\[(\mathbf{RX})_1 = \mathbf{r}_{12} \cdot \mathbf{x}_2 + \mathbf{r}_{13} \cdot \mathbf{x}_3 + \mathbf{r}_{14} \cdot \mathbf{x}_4\]This expression is nothing more than a weighted sum of the neighbors of \(X_1\), which could serve to approximate the marginal probability of \(X_1\) based on the random variables that it is conditioned on, namely \(X_2, X_3\) and \(X_4\). This, I believe, is the crux of why it is valid to use a simple matrix multiplication operation (and by extension, an MLP) to perform updates of all the nodes in a graph. By the very nature of the matrix multiplication with this reference operator, only connected nodes will pass their information to their neighbors, otherwise the weight for their contributions is simply 0.

Now, in addition to reference operators, we may want to also transform our node attributes. This can be useful if we want to extract useful features from our graphs that we think may help us achieve some learning task (think back to MolGAN which used graph convolution to look for features of small molecules that made them well suited to be water soluble, for example). To extract features from our graph, we can use filters, \(\Theta\), just as we would in a classic convolutional neural network (you could also think of these as simply transforming the graph into some latent representation that helps the GNN learn to perform the desired function efficiently). We can write the transformations \(R\) and \(\Theta\) operating on a graph signal as follows [8]:

\[\mathbf{X}’ = \mathbf{RX\Theta}\]Grattarola credits the 2017 paper by Gilmer et al. [10] for introducing the specific message-passing neural network, and we’ll see in a moment that the framework dovetails well with the basic concept of message passing as a form of variable elimination that we explored above [9]. We can summarize message passing in GNNs as requiring 3 steps [9, 10]:

-

Each node computes a message for its neighbors. The message function can be written as \(m(\text{node}, \text{neighbor}, \text{edge})\).

-

The messages are sent and each node aggregates all of its messages. Typically the aggregation is a simple sum or average.

-

The nodes update their attributes given the current values of those attributes and the aggregated information from the messages.

Note that these steps happen simultaneously for all nodes in the graph so in one message passing step, all the nodes of the graph are updated. So what does this look like in terms of our simple GNN written above? Let’s break it down [9]:

-

Message: Each node, \(i\), receives a message from each neighbor, where each message is the transformed graph signal, \(\mathbf{\Theta}^T \mathbf{x}_j\), where each neighbor is \(j \in \mathcal{N}(i)\).

-

Aggregate: The messages are aggregated via the weighted sum, which is simply performed as matrix multiplication with the reference operator, \(\mathbf{R}\).

-

Update: Now each node replaces its attributes with the new ones it computed in the previous step. If the diagonal of the reference operator is non-zero, then we will combine the new messages with a set of self-loop messages.

This simple approach is the equivalent of the message passing that we saw previously in the discussion about exact inference. The nice thing is that as long as each step (message, aggregate and update) is differentiable, then our model can learn optimal values for these functions to accurately complete the task at hand [9].

Conclusion

I hope you found this exploration a little bit helpful in understanding what GNNs are doing and why it works. This post was a drill down to answer a particular question I had, but if any of the topics I mentioned here were interesting to you, I would strongly encourage you to look at my references or other sources to learn more - I love this topic!

Footnotes

*1 I always wonder why this kind of probability is called a “marginal probability” and according to Wikipedia it is because if you were doing this calculation for, say, a tabulated set of probabilities, to calculate the marginal probability you would have to calculate the sums over the other variables in the margins of the table [4]. Like okay, fine, I guess, if everything we did was still pencil and paper? I’m sure there’s a catchier name out there somewhere, that’s all.

References

[1] Koller, D. and Friedman, N. Probabilistic Graphical Models: Principles and Techniques. MIT Press, 2009.

[2] Xing, E. “Lecture 4: Exact Inference.” 10-708 Probabilistic Graphical Models, Spring 2017. Carnegie Mellon University. https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~epxing/Class/10708-17/notes-17/10708-scribe-lecture4.pdf Visited 18 Jun 2022.

[3] Kuleshov, V. and Ermon, S. “Variable Elimination.” CS228 Probabilistic Graphical Models, 2022. Stanford University. https://ermongroup.github.io/cs228-notes/inference/ve/ Visited 18 Jun 2022.

[4] “Marginal distribution.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marginal_distribution Visited 18 Jun 2022.

[5] Kuleshov, V. and Ermon, S. “Junction Tree Algorithm.” CS228 Probabilistic Graphical Models, 2022. Stanford University. https://ermongroup.github.io/cs228-notes/inference/jt/ Visited 18 Jun 2022.

[6] Battaglia, P. W., Hamrick, J. B., Bapst, V., Sanchez-Gonzalez, A., Zambaldi, V., Malinowski, M., Tacchetti, A., Raposo, D., Santoro, A., Faulkner, R., Gulcehre, C., Song, F., Ballard, A., Gilmer, J., Dahl, G., Vaswani, A., Allen, K., Nash, C., Langston, V., … Pascanu, R. (2018). Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv: 1806.01261. http://arxiv.org/abs/1806.01261

[7] Sanchez-Gonzalez, A., Heess, N., Springenberg, J. T., Merel, J., Riedmiller, M., Hadsell, R., & Battaglia, P. (2018). Graph Networks as Learnable Physics Engines for Inference and Control. Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, 80, 4470–4479. http://proceedings.mlr.press/v80/sanchez-gonzalez18a.html

[8] Grattarola, D. “A practical introduction to GNNs - Part 1.” 3 Mar 2021. https://danielegrattarola.github.io/posts/2021-03-03/gnn-lecture-part-1.html Visited 18 Jun 2022.

[9] Grattarola, D. “A practical introduction to GNNs - Part 2.” 12 Mar 2021. https://danielegrattarola.github.io/posts/2021-03-12/gnn-lecture-part-2.html Visited 18 Jun 2022.

[10] Gilmer, J., Schoenholz, S. S., Riley, P. F., Vinyals, O., & Dahl, G. E. (2017). Neural Message Passing for Quantum Chemistry. 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2017, 3, 2053–2070. http://arxiv.org/abs/1704.01212