Making a Hash of Hash Tables

Welcome back to another blog post about computer science basics by a wannabe coder. This time we are going to talk about hash tables, which Gayle Laakmann McDowell says is one of the most important topics to know for a coding interview [1]. This post will be heavily influenced by Davide Mastromatteo’s excellent article on the subject [2]. We’ll talk about why hash tables are useful, what hash functions are, and how common problems with hash tables, like collisions, can be managed. You can also see an implementation of hash tables in Python (drawing heavily from [7]) here. Let’s get started!

What are Hash Tables?

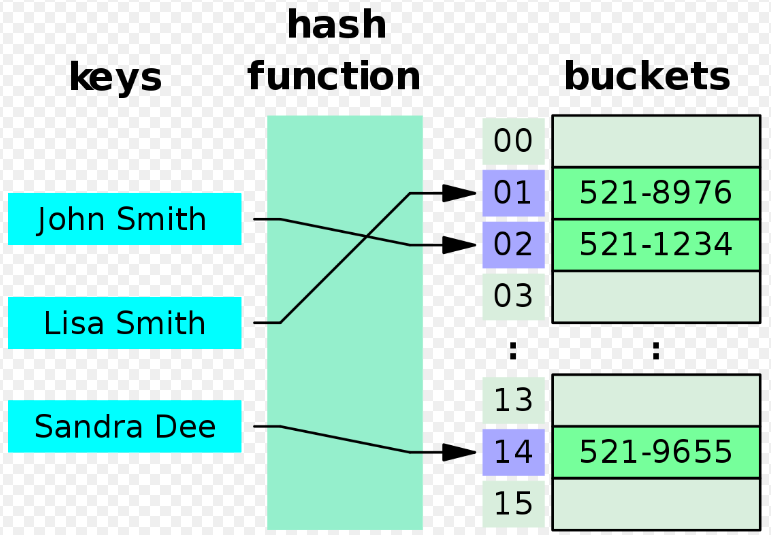

Hash tables are a data structure that store data as key-value pairs [1-2]. The hash table contains many buckets to store data, and each bucket has an index. The key in the key-value pair is used to determine the correct index for the correct bucket in which to store a specific key-value pair. The correct index is determined via a hash (or hashing) function [1-2]. Specifically, the hash function takes as input the key from a key-value pair (of any length), and returns a fixed length index that can be used to store the data in a specific bucket in the hash table [1-2]. Figure 1 illustrates how a phone book can be stored as a hash table. The names of people in the phone book are used as keys - they are passed through a hash function to determine where in the hash table their values (i.e. their phone numbers) should be stored.

Figure 1 - Source [3]

Hash tables can, on average, be much more efficient than other kinds of table lookup structures, which is why they are popular tools [4]. For example, they are used in database indexing, caches and sets [4].

There are two very interesting aspects to hash tables that I am going to discuss here. First we will look in detail into how hash functions work, and second, we will see how we can handle situations where we want to store multiple pieces of data in the same bucket in the table.

Hash Functions

Hash functions must take a key that can be any length and convert it to a fixed length value [2]. There are many different kinds of hash functions, but in general they are fast to compute [2]. They are also deterministic - that is, they do not use any element of randomness in how they generate the fixed length outputs*1 [2]. This is important because you should be able to get the same output fixed length value for the same input key every time [2].

But hash functions are also often one-way functions - this means that even though they should return the same result every time for a given input, you should not be able to determine what the input key was from the output fixed length value [2]. This property of being a one-way function makes hash tables more secure [2]. For example, if your password was being used as the key to a hash table that stored your personal data, you would not want a malicious hacker to take the output of that table’s hash function and back-calculate what your password is [2].

There is a downside to these properties of hash functions, though: it is possible to have collisions [2]. That is, it is possible for two input keys to map to the same output value (of a fixed length). This would mean that both key-value pairs should be stored in the same bucket in the hash table [2]. Let’s think about why that is for a second: if a hash function’s allowable inputs can be any length, then that means that there is an infinite number of inputs to the function [2]. But if the hash function’s outputs are fixed length, then there are a finite number of outputs available [2]. That means that, at some point, two inputs must be mapped to the same output by the hash function [2]. In the next section of this post we will talk about how we can resolve collisions, but right now it is enough to be aware that this problem exists.

Another important thing to understand about hash functions is that not all data types can be hashed [2]. In fact, only immutable data types are hashable in Python [2]. Mutable and immutable data types are interesting and deserve their own post, so for the purposes of this conversation we will just say that immutable data types cannot be changed after they are created [5]. Immutable data types include numeric data types, strings, bytes, and tuples [5].*2 The keys of every key-value pair that is added to a hash table must be immutable (and therefore hashable) [2].

Now that we have some intuition for how hash functions work, let’s learn more about what we do when two inputs to the hash function have the same output value.

Handling Collisions in Hash Tables

When two inputs to the hash function result in the same output, that is called a collision [1-2]. A collision means that two key-value pairs will have to be saved in the same bucket in the hash table. This is not necessarily bad, but it does mean that we need to come up with a strategy for helping the user find the specific key-value pair that they want from the multiple entries in a single bucket.

Before we consider some commonly used strategies, though, is there a way to eliminate collisions entirely? No, there isn’t, because of the fact we discussed above - that the output of a hash function must be of finite length, and therefore there are a finite number of outputs. We can add lots of buckets to the hash table so that the probability of a collision occurring becomes exponentially small, but this is not space efficient [2]. So we will look at other ways to manage collisions efficiently.

There are two commonly used methods for managing collisions [2]:

-

1) Separate chaining

-

2) Open addressing (with linear probing) [1]

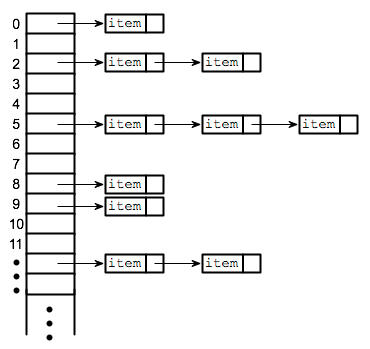

Separate chaining involves implementing another data structure inside of each bucket in the hash table. For example, if each bucket was a linked list, then we could enter each key-value pair as a new entry in the linked list*3 [2, 6]. This idea is shown in Figure 2, and is very common in practice [1].

Figure 2 - Source [6]

This method works fairly well because now the lookup cost is only the cost of scanning through the linked list in the correct index for your key [6]. If we assume that the distribution of elements in the hash table is relatively balanced, then the runtime will be proportional to the average number of elements in the table [6]. If the hash table is horribly imbalanced, the worst case runtime is O(n) where n is the number of elements in the hash table [6]. Generally, you should use linked lists for separate chaining if you expect to have a relatively small number of collisions [1]. If you expect a highly nonuniform distribution of hashings, then using binary search trees is a better option because the runtime to search them is O(log N) [1].

The second method for handling collisions is open addressing, where the basic principle is that if the bucket that you want to use is occupied, then you should use a different bucket that is empty [2]. The problem with open addressing is that if you need to delete an item, then you need to do a logical deletion instead of a physical deletion [2].

What?

Physical deletion means that you completely remove an entry from the hash table so that there is no record it was ever there [2]. It is like completely removing the node from a linked list in a bucket in the hash table. Let’s say for instance that we add a new name, “Jane Doe,” to our telephone book hash table example from Figure 1. Let’s say that “Jane Doe” collides with “Lisa Smith” at index 01. So we put “Jane Doe” in the next available bucket, 03 (the term linear probing implies that we will put the entry in the next available bucket by moving linearly through the indices [1]). But now let’s delete the entry “Lisa Smith” from our table. If I now tried to look up “Jane Doe” in bucket 01, I would assume that there was no “Jane Doe” entry in the hash table because it’s not where it’s supposed to be, in bucket 01.

But I know that “Jane Doe” is in my hash table! I just had to move that entry to bucket 03 because bucket 01 had been occupied! This is the wrong outcome! So in this case, physical deletion - the act of completely removing “Lisa Smith” and any record of that entry from the hash table - has caused serious problems for me [2]. I need to use logical deletion instead.

Logical deletion means that when I delete the “Lisa Smith” entry from my table, I need to leave behind a dummy value for my hash table. This dummy value tells the interpreter that is managing the hash table to consider the bucket empty for insertions but occupied for retrieval [2]. This is a bit more complicated method, but it is frequently used in practice. For example, Python dictionaries are built with hash tables and the open addressing method for collision resolution [2].

Open addressing is efficient when the number of collisions are low, but there are two disadvantages to using open addressing that don’t exist for separate chaining [1]. First, the total number of entries in a hash table is limited by the table array size; this is not true in separate chaining if you are using a data structure like linked lists where you could continue to add entries forever [1].

The second disadvantage to open addressing is called clustering, where the entries in a hash table will form clusters instead of being uniformly distributed within the hash table [1]. This is because if, for example, indices 20-29 are filled in an array of size 100, then there is a 10% chance that the next index you will fill will be index 30 [1]. Think about it - if your hash function originally has a 1% chance of sending you to any particular index, then you have a 9 x 1% = 9% chance of hashing to indices 20-29, which will all send you to the next available index, which is index 30. (You also still have a 1% chance of hashing directly to index 30, for a total probability of 9% + 1% = 10%.)

One way to deal with clustering is, instead of using linear probing, we use either quadratic probing or double hashing [1]. These methods ensure that the probing distance for the next available bucket is not 1 (or some constant) [1]. Instead, quadratic probing ensures that some quadratic distance is used, and double hashing uses a second hashing function to choose the distance used to probe for the next available bucket [1].

I hope this post has helped shed a little light on hash tables. There is more to learn here - like how they can be used in the Rabin-Karp substring search algorithm [1] - but for now I’m going to close because that felt like a lot of material to learn in one sitting!

Footnotes:

*1 There is an exception to this. Starting with Python 3.3, strings and byte objects are salted with a random value before they are converted to an index via a hashing function [2]. This random element will cause the hashing function to return different indices for the same input, so why do we do that? Salting is a security feature for situations where user data is stored using passwords as the key in a key-value pair. In this case, a fully deterministic hash function would return the same value every time for a set of commonly used passwords. So if a hacker knew the hash function in use, and they had a list of outputs of the hash function for a set of commonly used passwords, they could very easily steal a lot of users’ passwords. By adding the salting feature to the hashing function, there is no way that a hacker could determine a user’s password from the output of the hash function [2].

*2 Custom-defined objects (like classes) are also hashable by default [5]. The ID of the object is used as the key for the hash function, and different instances of the same class will have different IDs and therefore different outputs from the hash function [5].

*3 We are not constrained to use only linked lists for buckets in a hash table. Binary search trees are also commonly used because they use less space, can be traversed in O(log N) time and sometimes are more appropriate in certain applications [2].

References:

[1] Laakmann McDowell, G. Cracking the Coding Interview, 6th edition. 2016. CareerCup, LLC.

[2] Mastromatteo, D. “Python Hash Tables: Understanding Dictionaries.” The Python Corner. 21 Aug 2020. http://thepythoncorner.com/dev/hash-tables-understanding-dictionaries/ Visited 09 Jan 2021.

[3] Jorge Stolfi, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

[4] “Hash table.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hash_table Visited 09 Jan 2021.

[5] Li, L. “Immutable vs Mutable Data Types in Python.” Towards Data Science on Medium. 17 Oct 2019. https://towardsdatascience.com/immutable-vs-mutable-data-types-in-python-e8a9a6fcfbdc Visited 09 Jan 2021.

[6] Garg, P. “Basics of Hash Tables.” Hacker Earth. https://www.hackerearth.com/practice/data-structures/hash-tables/basics-of-hash-tables/tutorial/ Visited 16 Jan 2021.

[7] Grice, S. “How to Implement a Hash Table in Python.” Medium. 23 Nov 2017. https://stephenagrice.medium.com/how-to-implement-a-hash-table-in-python-1eb6c55019fd Visited 16 Jan 2021.