How To Git

In this first post about using git, a version control system, I am going to explain how it works conceptually, and how to complete basic tasks using the command line. For much more detail I would highly recommend the Software Carpentry tutorial on this topic as a starting point - I wish I had found it years ago! In a future post I will explain two workflows for using git - git-flow and github-flow.

How Git Works Conceptually

Introduction

Git is a distributed version control system where the complete codebase (including the version history) is stored on the computer of every developer working on that codebase [1]. The changes to files are tracked between computers [1]. Git is an incredibly powerful tool which can be used by a solo developer or by large teams. A note for non-coders out there - git can also be used for saving files other than code - Software Carpentry actually recommends that a good practice for open source science is to put all the files for a project into a repository available online, where the code is one component of that repository, in addition to raw data, corresponding publications, etc [2].

This brings us to a good place to start explaining what git is - git itself is a version control system that you can use locally, on your own computer, and which you can extend to cloud storage as well. For example, you can have a copy of a codebase stored on your own computer in a local repository, and have that same repository stored on a remote server. You probably are familiar with some remote servers already, like GitHub and Bitbucket. The advantage of using a remote server is that it makes it easier to share your repository with others; even if you want to keep your files private, you can use the remote server as a backup. The instructions we review here will apply to both repositories (aka repos) stored locally and remotely.

Basic Workflow

Figure 1 below is a helpful illustration of the steps required to store files in git - all of the commands in the blue arrows are instructions to provide in the command line [2]. First, you create and edit the files locally. When you are ready to add them to your repository and keep track of them using git, you use the command git add [2]. This moves the files to a staging area where you can prepare to add them to the repository. The staging area might seem redundant, but it is a good place to add files as you make changes, and then you can move subsets of files from the staging area to the repository. The staging area is also the place where files sit while you are trying to resolve any conflicts between versions of the same files or duplications of the same file in the same directory. Once all conflicts are resolved and you are ready to add the files to your repository, the command git commit adds the files to the local copy of the repository [2]. The value of keeping files in the repository is that now that they are committed, git will track how they are changed over time. If you have a remote repository (stored somewhere else besides your local computer) you will also need to run the command git push origin to add your files to the remote copy of the repository [2].

Figure 1 (Source [2])

Command Format

Notice that commands to git are always written in the following format: git [verb] [options] [2]. For example, you can commit files (i.e. move them from the staging area to the repository) by using the following command: git commit -m. The flag -m will allow you to write a short commit message to mark the commit. We will go into commit messages in more detail next because it is very important to learn to write them well.

Writing Good Commit Messages

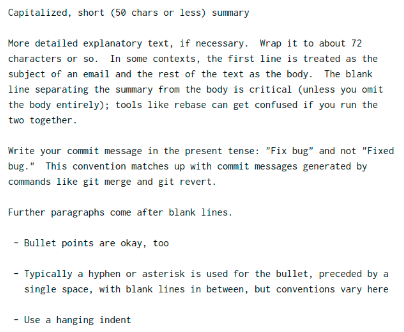

In my research I found that this topic comes up a lot in discussions on git, because most developers who collaborate agree that well-written, easy to grok* commit messages are the ones that get reviewed and accepted, and messy commit messages get ignored [3-4]. Forever. First of all, to write a commit message, use the command git commit and then git will automatically open a text editor so that you can compose a commit message [2]. Figure 2 shows the preferred structure of a good commit message [3-4].

Figure 2 (Source [3-4])

Note that the subject line should always be written in the infinitive - you can think of it as completing the sentence “If applied, this commit will…” [2]. Later, when you want to review a series of commits, you can read the long-form versions in detail or compile the subject lines. In either situation, it will be much easier to track the progress of your repository if you have written effective messages.

Commits and the HEAD Pointer

Each commit marks an update to the repository - it’s like a new snapshot in time of your files. If you ever break your code, you will be able to go back to an earlier commit to find a working copy of the code that you had written earlier. In git, the HEAD points to the most recent commit [2]. You can change that by entering a “detached head” state, where you can move the HEAD pointer to point at some other commit in the timeline of your repo [2]. However, this is dangerous, and you do not want to make any changes while you are in a detached head state [2].

.gitignore Files

Earlier we said that git can be used to track all kinds of files, not just code. It may be, though, that you do not want to track updates to certain kinds of files, like data files or images [2]. In this situation, you can add a file to your repository called a .gitignore file to list out types of files that you do not want git to track [2].

Performing Basic Tasks in Git

Now that we have had some basic introduction to what git is, let’s walk through some of the basic tasks you will want to do with git. First we will discuss the basic collaborative workflow, and then how we deal with conflicts.

Basic Collaborative Workflow

Assuming you are the only person working on your files at the moment, you will typically use the following commands in command line to commit your work and update your repository [2]:

$ git pull origin master // this line pulls the latest work from the remote repository

$ git add [filenames] // this line moves the files you have edited to the staging area

$ git commit // this line moves the files from staging area to repository

$ git push origin master // this line updates the remote repository with the updates

Workflow for Conflicts

Conflicts occur when two people want to make changes to the same file and those changes conflict with each other. You will know this has happened because git will give you an error message telling you that it cannot commit your changes. It will prompt you to reconcile the differences manually, and it will mark the lines that commit. Specifically, when git marks conflicts in a file, the <<<<< HEAD line precedes our change [2]. The ====== precedes the conflict from the copy pulled from the remote repository, and the >>>>>> [commit number] follows the end of the conflict [2].

When you run into a conflict, here is the workflow for resolving it [2]:

(1) Pull changes from remote

(2) Merge the changes into local copy

(3) Push reconciled files again

That concludes this first post on using git. I will follow up with another post that reviews some common workflows for using git, and some more random tips.

*grok (verb) : to understand intuitively [5].

References:

[1] Gehman, C. “What is DCVS Anyway?” https://www.perforce.com/blog/vcs/what-dvcs-anyway Visited 03/20/2020.

[2] Software Carpentry. “Version Control with Git.” http://swcarpentry.github.io/git-novice/ Visited 03/20/2020.

[3] Hileman, J. “Changing history, or How to Git pretty.” 3 November 2011. http://justinhileman.info/article/changing-history/ Visited 03/20/2020.

[4] Pope, T. “A Note About Git Commit Messages.” 19 April 2008. https://tbaggery.com/2008/04/19/a-note-about-git-commit-messages.html Visited 03/20/2020.

[5] Wikipedia. “Grok.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grok Visited 03/23/2020.