Sampling Methods for Approximate Inference

In this post we are going to talk about sampling methods for use in performing inference over probabilistic graphical models. Last time, we talked about how sampling methods produce approximate results for inference and are best used on really complex models when it is intractable to find an exact solution in polynomial time [1]. Sampling methods essentially do what they say on the tin: they indirectly draw samples from a distribution and this assortment of samples can be used to solve many different inference problems. For example, marginal probabilities, MAP quantities, and expectations of random variables drawn from a given model can all be computed using sampling. Variational inference is often superior in accuracy, but sampling methods have been around longer and can often succeed where variational methods fail [1]. Let’s dive in to learn more about sampling.

Forward Sampling

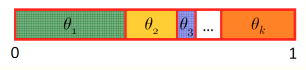

Probably the simplest sampling approach is to draw samples from a multinomial distribution, which has \(k\) possible outcomes and each one has a probability \(\theta_k\). We then draw samples from a uniform distribution [0,1] and depending on the value, we assign the outcome to the event \(k\) with the corresponding probability. Specifically, we divide the interval between 0 and 1 into \(k\) sections where each section has size \(\theta_k\), as shown in Figure 1 [1].

Figure 1 - Source [1]

We can extend this idea to a simple Bayes net containing multinomial variables, where we use forward sampling to compute the joint or marginal distributions by following the topology of the graph. Specifically, we start by drawing samples from the root nodes of the graph (those with no parents) and then we draw samples from their children by conditioning the children’s conditional probability distributions on the samples drawn from their parents. We continue this process until we have sampled from all the nodes in the graph, and this can be done in polynomial time [1]. There is a variation on this approach for undirected models as well provided they can be represented as clique trees [1].

Monte Carlo Estimation

Frequently with PGMs, we will want to compute expectations such as:

\[\mathbb{E}_{x \sim p}[ f(x) ] = \sum_x f(x) p(x)\]If the function \(f(x)\) doesn’t have a structure that matches the structure of \(p(x)\), we will need to use sampling to approximate the integral because we cannot compute it analytically*1. We can compute an approximation by drawing many samples from \(p(x)\) - in general, this approach is referred to as a Monte Carlo method [1]. (Monte Carlo methods are actually a broad class of strategies - you can use them to do everything from compute the area of a circle to performing inference!) The approximation of the expectation above using Monte Carlo can be written as [1]:

\[\mathbb{E}_{x \sim p}[f(x)] \approx I_T = \frac{1}{T} \sum_{t=1}^T f(x^t)\]Where T is the total number of samples drawn from \(p(x)\). If we take enough samples, the variance of \(I_T\) can be minimized so that the Monte Carlo approximation, \(\mathbb{E}_{x^1, …, x^T \sim p}[I_T] = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p}[f(x)]\) after sufficiently many samples have been drawn [1].

Markov Chain Monte Carlo

Building on the Monte Carlo idea, we can perform marginal and MAP inference using a sampling approach [1]. This approach is called Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). A Markov chain is a time series of random variables \(X_0, X_1, X_2,...\) where each random variable can take \(d\) possible values. Together the \(X_i \in \{1, 2, ... , d\}\) represent the state of a system changing over time. The probability distribution of the first random variable is \(P(X_0)\), and the probability of every state after that time is dependent only on the previous state, that is [1]:

\[P(X_i | X_{i-1})\]This is very important - each state in a Markov chain only depends on what happened in the immediate prior time step, and the rest of the system’s history does not matter. This transition probability distribution is the same at every time step, and that fact is called the Markov assumption [1]. We can represent the probability distribution as a matrix [1]:

\[T_{ij} = P(X_{new} = i | X_{prev} = j)\]So the probability of arriving at each state after \(t\) time steps is [1]:

\[p_t = T^t p_0\]Where \(p_0\) was the initial probability distribution at the first time step. Over many time steps, the Markov chain will often arrive at a stationary distribution defined as \(\pi = \lim_{t \rightarrow \inf} p_t\) (assuming such a limit exists) [1].

The reason that the MCMC algorithm is useful for sampling is that if we run it over many time steps, the transition probability will approach a stationary distribution that is equal to the probability distribution from which we want to sample. At a high level, here’s how the MCMC algorithm works [1]:

-

Inputs are a transition operator T and an initial state, \(X_0\). The transition operator describes a Markov chain with stationary distribution \(p\). The initial state \(X_0\) is a first set of values for the variables in \(p\).

-

Run the Markov chain from \(X_0\) for \(B\) time steps. This is called the burn-in time.

-

Continue to run the Markov chain for \(N\) sampling steps and collect all of the states that it visits - this is the stationary distribution which we are sampling from.

One useful thing that we can do using MCMC is to take the sample with the highest probability (i.e. the one that appears most often) and use it to estimate the mode of the probability distribution. This is essentially the MAP estimate [1].

Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm

The Metropolis-Hastings (MH) algorithm is one way to implement MCMC. The MH approach builds a transition operator, defined as [1]:

\[T(x’ | x) = Q(x’ | x) A(x’ | x)\]The transition operator is obtained using two pieces [1]:

- A transition kernel chosen by the user (often we use something simple like a Gaussian):

- An acceptance probability for transitions chosen by \(Q\), and written as:

MH begins with these components, and begins to build a Markov chain by choosing a new point \(x’\) according to \(Q\). Then we decide to accept the new state with some probability \(\alpha\), or keep the current state with probability \(1 - \alpha\). The probability distribution \(P\) is our stationary distribution [1].

The mechanism of the acceptance probability pushes our sampling towards regions of high probability within the distribution. Consider the expression for \(A\) above (and imagine that \(Q\) is just a uniform distribution). The value of \(A\) will be greater than 1 when \(\frac{P(x’)}{P(x)}\) is greater than 1, which happens when \(P(x’) > P(x)\) - that is, the acceptance probability is high when the probability of the new sample is greater than the old one. In this case, we accept the new sample with probability 100%. When the \(Q\) distribution alters this so that we accept a sample that actually results in a lower new probability \(P(x’)\), we only do this a small amount of the time [1].

Regardless of the choice of \(Q\), the MH algorithm always pushes the stationary distribution of the Markov chain towards \(P\). To see this, let us first introduce a concept known as the detailed balance condition. The detailed balance condition is a sufficient condition for a stationary distribution, and it states that [1]:

\[\pi(x’) T(x | x’) = \pi(x) T(x’ | x) \text{ } \forall x\]We can use this to show that the stationary distribution \(\pi(x)\) is equal to \(P(x)\) as follows. When \(A(x’ \text{given} x) < 1\), then:

\[A(x’ | x) = \frac{P(x’)Q(x | x’)}{P(x) Q(x’ | x)}\]Note that if \(A(x’ \text{given} x) < 1\), then the inverse expression is greater than 1:

\[\frac{P(x)Q(x’ | x)}{P(x’)Q(x|x’)} > 1\]And so \(A(x \text{given} x’) = 1\) because that is the acceptance probability for this inverse expression. This allows us to incorporate this expression \(A(x \text{given} x’)\) below:

\[P(x’)Q(x | x’)A(x | x’) = P(x)Q(x’ | x)A(x’ | x)\]And we can say that the transition probability is the product of \(Q\) and \(A\) thus:

\[P(x’) T(x | x’) = P(x) T(x’ | x)\]This equation exactly matches the detailed balance condition and therefore proves that the MH algorithm sets \(\pi(x) = P(x)\) [1].

MCMC methods are not perfect. As we mentioned in our previous post, there is no way to know for sure when we reach a globally optimal solution. Now that we have seen the MH algorithm, we can say more specifically that it is difficult to know when the burn-in time has drawn enough samples to cause us to reach the stationary distribution. It may be that for complex distributions, we will be stuck sampling within regions of high probability and it will take a very long time to sample from other regions as well to get an accurate representation of the overall distribution [1].

Footnotes

*1 This statement confused me a little bit, so I did a little more digging. Apparently, this equation is also known as the Law of the Unconscious Statistician [2]. The moniker apparently comes from the fact that many people use this equation while thinking that it is a simple fact, and not a law that was rigorously proved [2]. In other words, statisticians use it without being aware of the rigor of the statement, I guess? Anyway, the point is that when I looked through some examples of how to use and prove this rule as presented by in [3], I think that you would not be able to solve the integral unless the functions \(f(x)\) and \(p(x)\) had a nice mathematical relationship that you could exploit in analytically solving the integral.

References

[1] Kuleshov, V. and Ermon, S. “Sampling methods.” CS228 Probabilistic Graphical Models, 2022. Stanford University. https://ermongroup.github.io/cs228-notes/inference/sampling/ Visited 1 Jul 2022.

[2] “Law of the unconscious statistician.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Law_of_the_unconscious_statistician Visited 1 Jul 2022.

[3] Rumbos, A. “Probability: Lecture Notes.” 23 Apr 2008. https://pages.pomona.edu/~ajr04747/Spring2008/Math151/Math151NotesSpring08.pdf Visited 1 Jul 2022.