Explaining the Scallop Theorem

I am really excited to be writing this post because I have been working on my understanding of this topic for a long time, and I can’t wait to practice explaining it to others. Today I want to explain the Scallop Theorem, a central tenet of the microswimmer research that I am doing at Carnegie Mellon University. The Scallop Theorem was introduced in a seminal paper in 1977 by the Nobel Prize winning physicist, E.M. Purcell [1]. In my mind, it is also one of the most convivial scientific papers I have ever read, which makes coming back to it a joyful occasion, instead of the frustrating endeavor that it could have been. It is fun to read the paper in its entirety, but today I will focus on one particular part of it. Today, we will understand why it is so hard to build microswimmers.

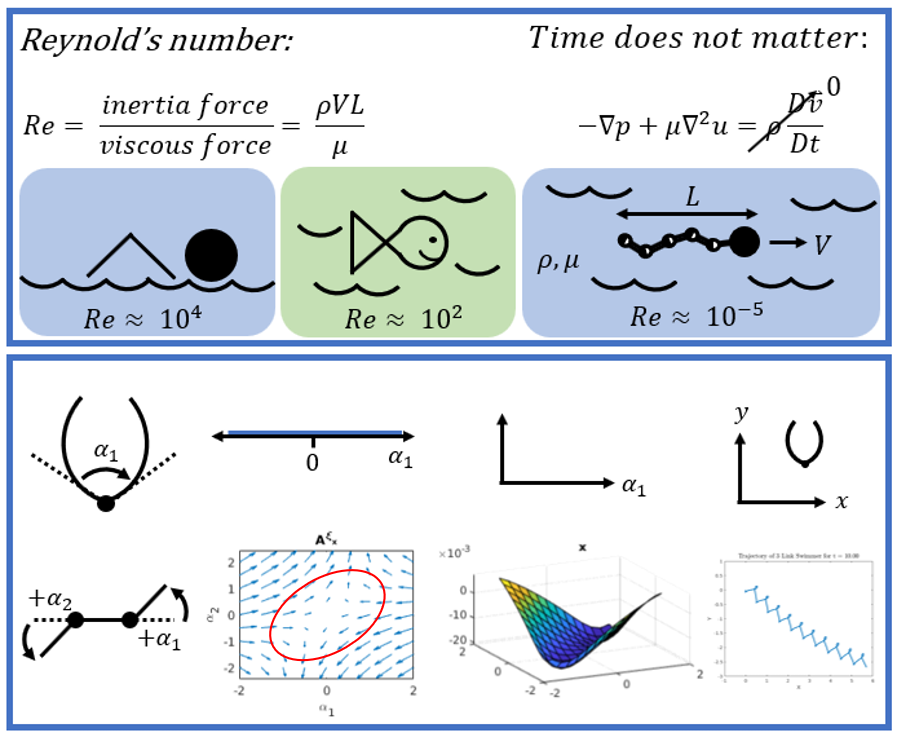

A quick note before we start: it helps to have some knowledge of fluid dynamics in order to understand the Scallop Theorem. I will follow up with some additional posts that communicate the derivations for Reynolds number and the Navier-Stokes equations for incompressible fluids. I should also mention that I am writing this post in preparation for my qualifying exams, so I have added a draft of one of my key figures to this post to help communicate the Scallop Theorem, see Figure 1.

Figure 1, [3] - [7]

For now, let’s start with a ratio called the Reynolds number. Reynolds’ number describes the ratio of the inertial to viscous forces acting on an object in a fluid flow [1],[2]. I will not go into the derivation of Reynolds’ number here, but Figure 1 shows the equation where [1]:

rho = density of the fluid

V = velocity of the fluid around the object

L = characteristic length of the object

mu = dynamic viscosity of the fluid

We can calculate the Reynolds number to describe the ratio of forces that any object will experience in a fluid flow. For example, a human has a Reynolds number on the order of 10^4 [1]. A goldfish has a Reynolds number of 10^2 [1]. But for bacteria, or the microswimmers that I work with in my research, their Reynolds numbers are MUCH smaller, on the order of 10^-5 [1]!

There is a special significance to having a Reynolds number this small. It means that the viscous forces dominate the system, and that the object in the fluid has essentially no inertia [1]. Intuitively, it means that you cannot build up any momentum as you swim through this fluid - if you were swimming using a crawl stroke in a low Reynolds number environment, you would stop moving as soon as your arm stopped pushing back on the fluid. You would not glide smoothly through the water, using your momentum to carry you along until you took another stroke - you would simply come to an abrupt halt!

We can describe this situation in terms of another fluid dynamics equation, the Navier-Stokes equation for incompressible, Newtonian fluids. You can see this equation in one of its more general forms in Figure 1 below where I show that the time-dependent terms in the equation will go to 0 in a low Reynolds number environment. You are left depending on the fluid forces that are applied to the body in the present moment to move you along. This is critical: in a low Reynolds’ number environment, time does not matter - your past actions do not matter, because you have no momentum. Your motion is dependent entirely on what you are doing at this moment.

So what does that look like for an example swimmer? This is where the famous scallop comes into play. If you recall, a living scallop (before you eat it) has a shell which it opens and closes to propel itself. The scallop opens its shell slowly, and then closes its shell quickly. This fast displacement of water builds up momentum which forces the scallop to accelerate forwards. In a low Reynolds environment, this is a useless maneuver. The scallop will experience a hydrodynamic drag force when it opens its shell to a certain degree, and it will experience the equal and opposite of that force when it closes its shell. It does not matter how quickly the shell moves, at low Reynolds number the result will be the same. The scallop will not achieve a net displacement to a new location [1].

I drew a diagram of the scallop in Figure 1. Next to it, I have drawn a plot of the scallop’s configuration space. The scallop’s configuration space is the collection of angles that its shell can take. Since the scallop only has one degree of freedom, its configuration space can be described along one axis. Other robots, such as the three-link swimmer also shown in Figure 1 (we will return to it in a moment), have a 2 dimensional configuration space because they have 2 degrees of freedom.

Are you with me so far? I am about to take a step that Purcell does not take in his paper, because this technique was not around in 1977, although it has become very useful since it was published in the robotics world [8],[9]. In two detailed papers, Choset and Hatton present a way of analyzing these plots of a robot’s configuration space to find out how far a robot would move for a given gait. The gait describes the motions of the robot’s links - it describes how the robot will move each of its links, and in what order, to translate through space. Choset and Hatton used a clever application of Stokes’ Theorem to calculate how far the robot would move for one complete cycle of its gait given this configuration space. I promise to go into detail on this technique too, but for now it is enough to have the intuition that the area inside the circle that describes a robot’s gait can translate to a net displacement for that robot.

So let’s go back to the configuration space for the scallop. Unfortunately, it is a one dimensional space, so we cannot even use Stokes’ Theorem to calculate its net displacement, because it does not have a net displacement for any gait in a low Reynolds number regime! However, if you look at the three-link swimmer, you can see that it does have a two dimensional configuration space, and we can draw an ellipse to describe a gait in this space, as shown in Figure 1. Then, using Choset and Hatton’s technique, we can calculate the net displacement that the three-link swimmer will achieve using this gait. For fun, I can also show you a video of the three-link swimmer moving through space, which I created in MATLAB.

Figure 2

References

[1] E. M. Purcell, “Life at low Reynolds number,” Am. J. Phys., vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 3–11, Jan. 1977.

[2] Benson, Tom. NASA Glenn Research Center. “Reynolds Number.” Last updated 06/12/2014. https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/BGH/reynolds.html Visited on 07/22/2019.

[3] Benson, Tom. NASA Glenn Research Center. “Conservation of Momentum: 1 Direction, Steady Flow.” Last updated 06/12/2014. https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/BGH/conmo.html Visited on 07/22/2019.

[4] Hosch, William L. Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Navier-Stokes equation.” Last updated 08/09/2018. https://www.britannica.com/science/Navier-Stokes-equation Visited on 07/22/2019.

[5] Gibiansky, Andrew. “Fluid Dynamics: The Navier-Stokes Equations.” Last updated 05/07/2011. http://andrew.gibiansky.com/blog/physics/fluid-dynamics-the-navier-stokes-equations/ Visited on 07/22/2019.

[6] SimWiki. “Numerics: What are the Navier-Stokes Equations?” https://www.simscale.com/docs/content/simwiki/numerics/what-are-the-navier-stokes-equations.html Visited on 07/22/2019.

[7] Wikipedia. “Divergence Theorem.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divergence_theorem Visited on 07/22/2019.

[8] R. L. Hatton and H. Choset, “Connection Vector Fields and Optimized Coordinates for Swimming Systems at Low and High Reynolds Numbers,” in ASME 2010 Dynamic Systems and Control Conference, Volume 1, 2010, pp. 817–824.

[9] R. L. Hatton and H. Choset, “Geometric motion planning: The local connection, Stokes’ theorem, and the importance of coordinate choice,” Int. J. Rob. Res., vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 988–1014, 2011.