ML Bonanza Episode 3 - Gradient of the ELBO

We are now on our third post about VAE’s, and this time we are going to do a deep dive into the probability that dictates how they function. If you recall from our last post, we ended on the observation that the encoder is learning a posterior distribution p(z given x) so that it can convert input data points, x, into a latent space representation, z. We saw that we can use Bayes’ Theorem to write an expression for this posterior distribution, but that it would be intractable to actually calculate the denominator in the expression, p(x). I hinted that we will find a way to approximate the posterior distribution p(z given x) instead, and that we will use the KL divergence to do so. Let’s figure out how this will work.

Using Variational Inference to Approximate the Posterior Distribution

We will use an approach called variational inference to find a way to approximate the posterior distribution p(z given x) [2,3]. Let’s say that we have an entire family of distributions, Q, which could represent the distribution p(x), and which we can write as [1, 2]:

Equation 1

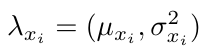

Where lambda is a variational parameter that identifies a specific distribution q from the family, Q [2]. For example, if a particular distribution, q, from the family, Q, was Gaussian, then we would say that lambda would represent the mean and variance for each of the latent variables, z, corresponding to the i-th data point, x-i, taken from the distribution, q [2]:

Equation 2

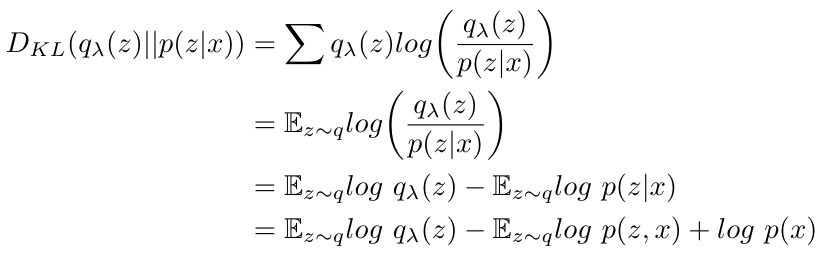

How well does this particular distribution, q(z given x) approximate the true distribution, p(z given x)? We can use the Kullback-Leibler divergence again to calculate the difference between the two distributions [2]. I introduced the KL divergence in my last post, and I can manipulate the expression given there until I get an expression containing 3 terms [1,2]:

Equation 3

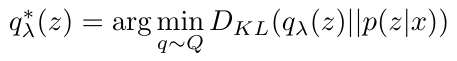

Now that I have this expression, I can say that I want to minimize the KL divergence (remember, the smaller the value of the KL divergence, the more likely the two distributions are to be identical) [1,2]. Mathematically, my optimal approximate distribution, q*(z given x), can be written as the argument that minimizes the KL divergence [1,2]:

Equation 4

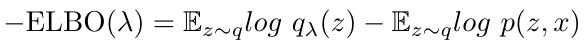

Cool story bro, but this does not actually solve our problem. Do you see that we still have the p(x) term in our expression for the KL divergence? Remember, it is intractable to compute p(x), that’s how we got into this mess in the first place. Let’s consider the first 2 terms in the expression above - I can combine them to get the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO) as follows [1]:

Equation 5

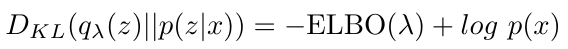

And this allows me to rewrite the KL divergence as the sum of the ELBO and log p(x) [1]:

Equation 6

Notice that I have written the ELBO as a function of lambda [1,2]. We could also say that the ELBO is a function of q [1,2]. The point is that only the ELBO is dependent on lambda and q, but log p(x) does not [1,2]. This is very important, because that means that in order to minimize the KL divergence, I only need to maximize the ELBO - I do not need to know what p(x) is or change it in any way [1,2]. This is great for us, because we can calculate the derivative of the ELBO for each data point and use those derivatives to perform gradient descent and update the weights on the encoder and decoder [1,2].

Computing the Gradients and the Reparameterization Trick

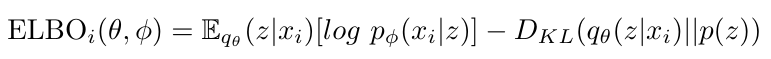

Let’s talk about how we can take the gradient of the ELBO. First, just a quick point of clarification: in general, a VAE model is expected to only have local latent variables - that means that for every data point x, there is a corresponding latent value z, and no data point x will share their value of z with another data point [2]. This means that we can break the expression for the ELBO down into a sum over all of the data points, x. The ELBO for one data point is [2]:

Equation 7

We did some mathematical manipulations to write ELBO in this form, but it is equivalent to the expressions above [2]. I want to pause here and discuss lambda, theta and phi. Lambda refers to the mean and variance of the approximation of the posterior distribution, q(z given x) [2]. We are trying to find an optimal value for lambda which will maximize the ELBO - that optimal value for lambda will tell us what the optimal posterior distribution q*(z given x) is [2]. Now, the encoder neural network is the approximation of this optimal posterior distribution [2]. That means that, to some extent, finding the optimal value of lambda is doing the same thing as finding the optimal weights of the encoder neural network, theta. This is the connection between our probability perspective on VAEs and our neural network perspective. (In both cases, the weights, phi, optimize the decoder network.) Let’s keep going through the math to see how we arrive at the same loss function as before by using this probability approach.

Keeping in mind that lambda and theta are both parameters of the encoder that must be optimized, we can rewrite the expression for the ELBO for a single data point as follows [2]:

Equation 8

Do you see that this expression is the same loss function as we had found previously (accounting for a minus sign)? We still have the reconstruction loss and the regularizer term, and we can still sum over all the losses for individual data points.

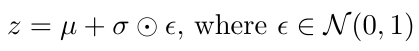

One big question remains - when I take the derivatives of the ELBO, how do I calculate the derivative of the approximation of the posterior distribution, q(z given x)? This is difficult because the random variable, z, is stochastic; if we took the derivative of q(z given x) with respect to its parameters, we would get large errors because the distribution is inherently random [1]. We need to take the stochasticity “out” of the derivative (i.e. make the stochasticity of the variable independent of the parameters that we are taking the derivative with respect to), and we can do this by using something called the reparameterization trick [1,2].

In short, the reparameterization trick says that I can write a deterministic (not stochastic) expression for the random variable, z, as follows [1,2]:

Equation 9

Where the standard deviation is multiplied by some error that is itself stochastic [1,2]. This expression now makes it possible for me to take the derivative of the random variable, z.

If this last explanation about the reparameterization trick felt unsatisfying to you, then don’t worry, I feel the same way. In my next post, I will go through it in more detail. That point aside, however, we are now done with our explanation of how VAEs work. If you would like more information, or to see these VAEs implemented in Python, then please visit my references [1] and [2] for more detail. Thanks for sticking with me, and stay tuned for more posts soon!

References:

[1] Stewart, M. “Comprehensive Introduction to Autoencoders.” 14 April, 2019. Medium: Towards Data Science. https://towardsdatascience.com/generating-images-with-autoencoders-77fd3a8dd368 Visited 24 March 2020.

[2] Altosaar, J. “Tutorial - What is a variational autoencoder?” https://jaan.io/what-is-variational-autoencoder-vae-tutorial/ Visited 06 May 2020.

[3] Wikipedia. “Variational Bayesian methods.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Variational_Bayesian_methods Visited 06 May 2020.