Writing System Dynamics in Discrete Time

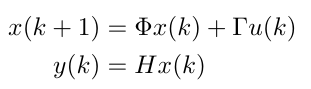

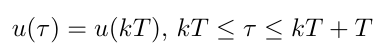

In my last post, I introduced the concept of discrete time for digital systems. We discussed difference equations and the z-transform. In this post, we are going to use these ideas to write the standard state space expressions for a system’s dynamics in discrete time. That is, we are going to find the matrices phi, gamma and H for the discrete system dynamics as written below [1]:

Equation 1

This post is going to be a lot of math so I am going to split it up into parts and walk us through all of it. Let’s go!

Solving for x in the Dynamics

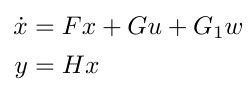

Since our objective is to write the system dynamics in discrete time, it makes sense to start with the known system dynamics in continuous time. We are trying to solve for x in the following system of equations in continuous time [1]:

Equation 2

(The w term contains any disturbances we might see in the system.) We can solve for x in two parts by considering two possible cases: (1) we compute x given initial conditions and assuming that there is no external input, and (2) we also compute x if there is an external input given [1]. Let’s look at each case in turn.

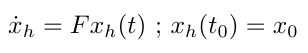

1 - Find x from Initial Conditions, u = 0

Here we begin by assuming that the solution to the dynamics when u = 0 takes the form of some homogeneous equation like so [1]:

Equation 3

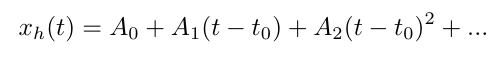

We are also going to assume that the homogeneous equation is smooth enough to be approximated with a series expansion that looks like this [1]:

Equation 4

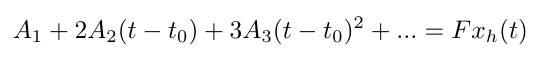

If I calculate the derivative of Equation 4, I can substitute it into Equation 3 on the left hand side. This gives me the following [1]:

Equation 5

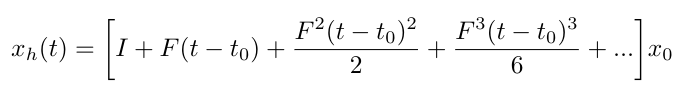

Okay, the next step is a little confusing to me, and if someone can explain why the math works this way, I would really appreciate hearing about it. The authors in [1] state that we differentiate Equation 5 again and end up with this [1]:

Equation 6

Again, I am not sure how we get here, but it turns out that the sequence inside the brackets is a series approximation for a matrix exponential. In other words [1]:

Equation 7

Equation 7 is a unique solution to the original dynamics in Equation 2, and it has some interesting properties that we can exploit later when we are solving for x in the presence of an external input. Let’s see how that works.

Special Properties of the Homogeneous Solution for No External Input

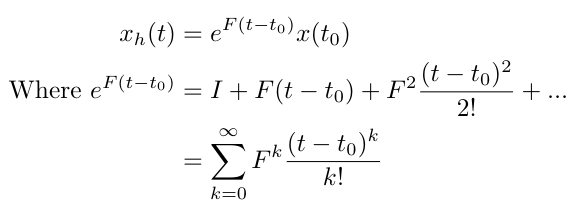

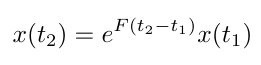

Let’s consider what the value of x, as expressed in Equation 7, looks like when t takes on two different values. We find that [1]:

Equation 8

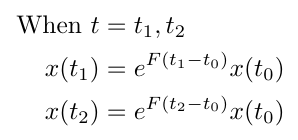

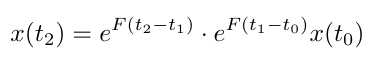

Since t0 is arbitrary, I can rewrite x at time t2 as [1]:

Equation 9

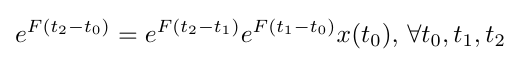

Notice that I can substitute the expression for x at t1 into the expression for x at t2 [1]:

Equation 10

Since the solution for x at t2 is unique, the two expressions, Equations 9 and 10, must be the same [1]:

Equation 11

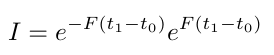

Finally, if I were to set t2 = t0, then I would find that [1]:

Equation 12

This means that we can find the inverse of exp(Ft) by changing the sign of t [1]. This might seem random, but it is going to come in useful in the next section, where we solve for x in the presence of an external input.

2 - Find x When u is Nonzero

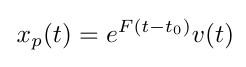

In this section, we are going to find the second half of the solution to x, assuming that there is a nonzero external input. We will use a technique called variation of parameters to find the solution [1]. We begin by assuming that the solution to x is in the form [1]:

Equation 13

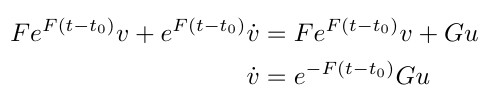

Where v(t) is a vector of variable parameters [1]. We can substitute Equation 13 into Equation 2 to get the following [1]:

Equation 14

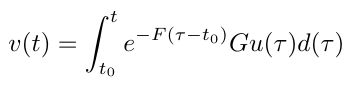

We are assuming that there is no control input before time t0, so we can integrate the derivative of v from t0 to time t [1]:

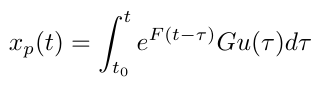

Equation 15

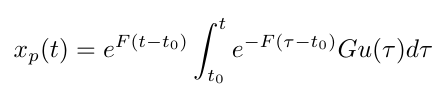

I’m using tau as a dummy variable for time here since I’ve already used t in the integral definition and I don’t want to overload notation. Now I can substitute this integral into my solution for x in Equation 13 [1]:

Equation 16

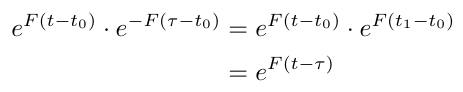

And now I’m going to use the interesting property that we laid out in the previous section. I can rewrite the exponents in Equation 16 as one term as follows [1]:

Equation 17

Now this gives me a new form for my solution [1]:

Equation 18

I now have my second half to my solution for x. In the next section, we are going to pull this all together and find expressions for the matrices phi, gamma and H from Equation 1.

Pulling It All Together

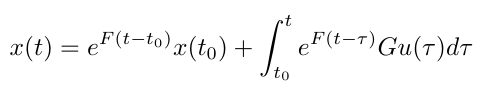

My total solution (neglecting disturbances) can now be written as [1]:

Equation 19

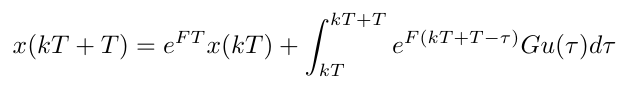

Remember, the whole purpose of this blog post is to write the dynamics in discrete time. Here is where we are going to make the switch from continuous to discrete time. We are going to rewrite Equation 19 as a difference equation by letting t = kT + T and t0 = kT. Then we can say [1]:

Equation 20

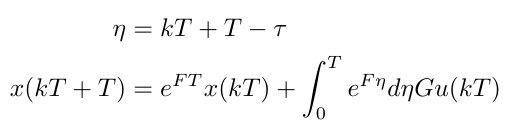

Notice that Equation 20 is not dependent on the type of hold we use to sample the output [1]. The control input, u, is specified in terms of the continuous time history over the sample interval, whatever that may be, but it is independent of the type of hold that spans the sample interval [1]. If we assume we are using a zero-order hold (ZOH), with no delay, then we can rewrite u as [1]:

Equation 21

Now if we want to solve the integral for the case where we are using a ZOH with no delay, we can use a change of variables from tau to eta [1]:

Equation 22

Notice that we were able to pull out the G u(kT) term because it is a constant over the time interval.

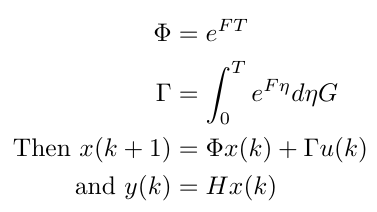

We are almost there. If I define phi and gamma carefully, I can now cast Equation 22 in the form we were originally looking for (Equation 1) [1]:

Equation 23

And we’re done! We have successfully derived the mathematics that we use to rewrite dynamics in continuous time into dynamics in discrete time.

Unfortunately (I hate to say this after all of our hard work), in practice we never need to actually do this math ourselves. If you are working with controls libraries like MATLAB’s Controls Toolbox, then you can use functions like c2d() to do this conversion automatically. But I will say that it is always good to understand what is happening under the hood, and now we have a very good idea of what must be done to switch from continuous to discrete time.

References:

[1] Franklin, G., Powell, J., Workman, M. “Digital Control of Dynamic Systems, 3rd Ed.” Ellis-Kagle Press, Half Moon Bay, CA, 1998.