How to Derive Equations of Motion

Although I do not think it is going to play a major role in our upcoming controls qualifying exam, I realized that I could not remember how to derive the equations of motion for some simple systems. Here I am going to present some examples out of the undergraduate textbook [1] and in a future post I would like to focus on something a little more challenging, like the levitating magnetic ball.

The basic approach to deriving the equations of motion for any system is [1]:

(1) Pick a convenient coordinate system (it should make the math easy).

(2) Determine the forces using a free body diagram.

(3) Solve for the equations of motion.

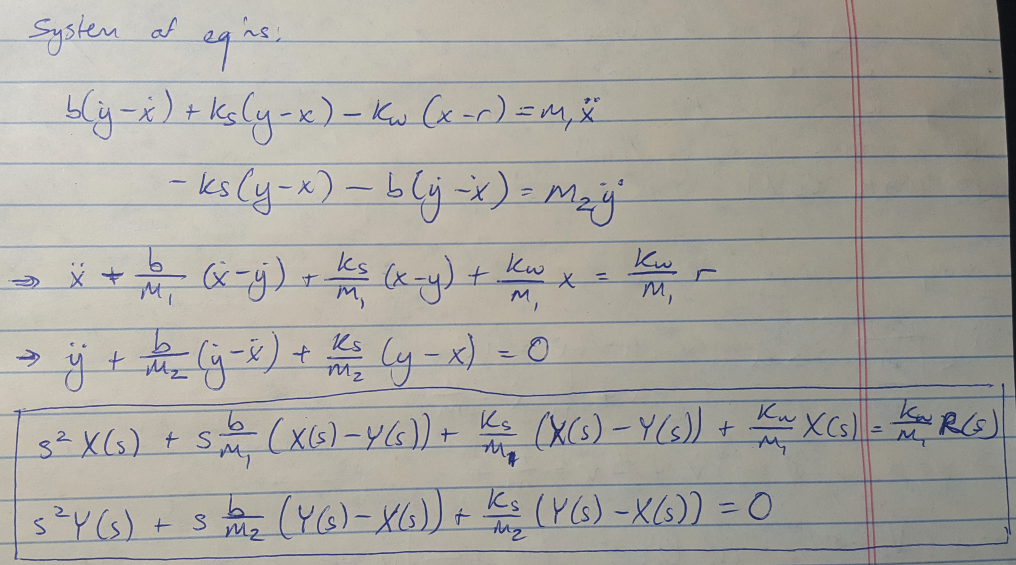

We can subsequently apply the Laplace transform (or assume that the solution to the differential equation takes the form shown below) and obtain the equation of motion in the frequency domain [1]. This expression can be rearranged to obtain the transfer function [1]. I explain this process in detail in the examples below.

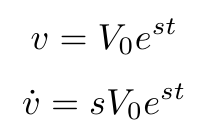

Example 1: Cruise Control [1]

Here we assume the car is a mass experiencing some friction (determined by the coefficient b) as it moves at a constant velocity along a flat road. Once we obtain the equation of motion in the time domain, we can assume that we can write both the output velocity and the control input in the form shown above. Since the solution includes the variable “s” we can use it to write the transfer function in the frequency domain.

Figure 1 - Example 1

Figure 1 - Example 1

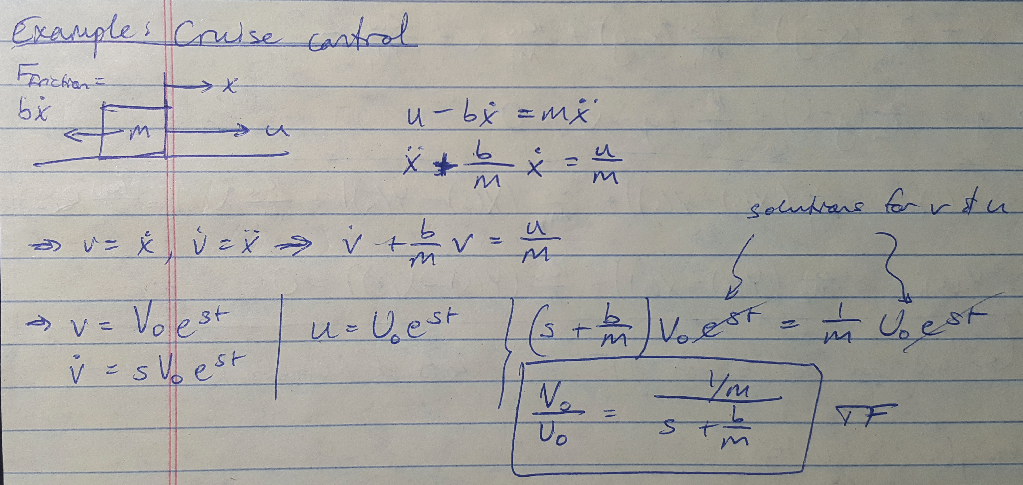

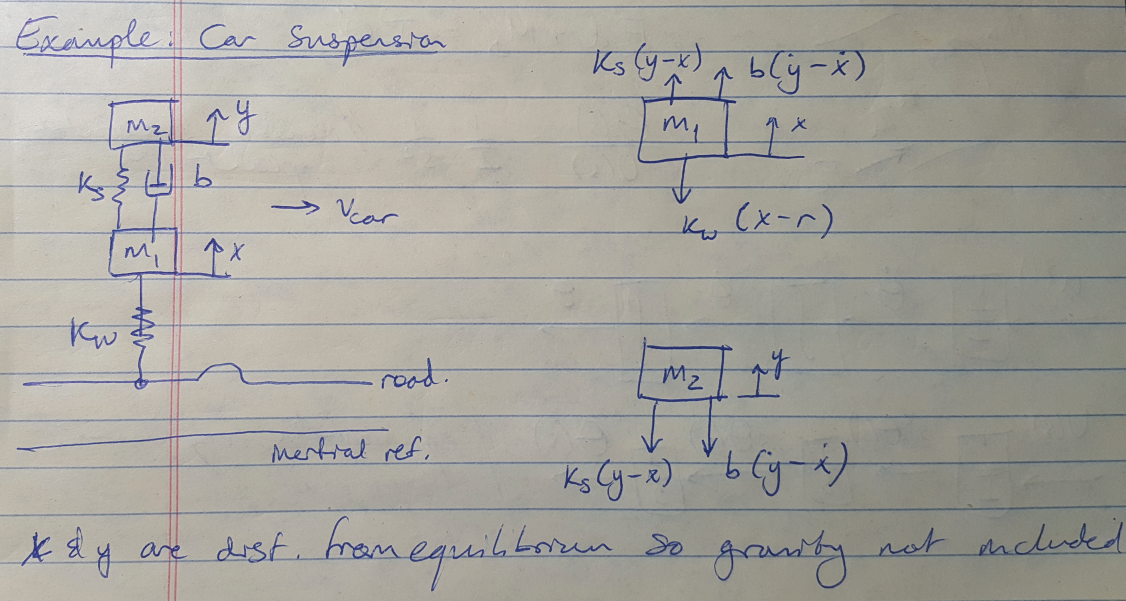

Example 2: Car Suspension [1]

This example shows how to handle multiple coordinates, or states, that we have to track. I terminate this example when I get both equations in the frequency domain, but you could carry on and solve the second equation for X(s) and plug that into the first equation to obtain the transfer function Y(s) / R(s) for the system.

Figure 2 - Example 2

Figure 2 - Example 2

Figure 3 - Example 2

Figure 3 - Example 2

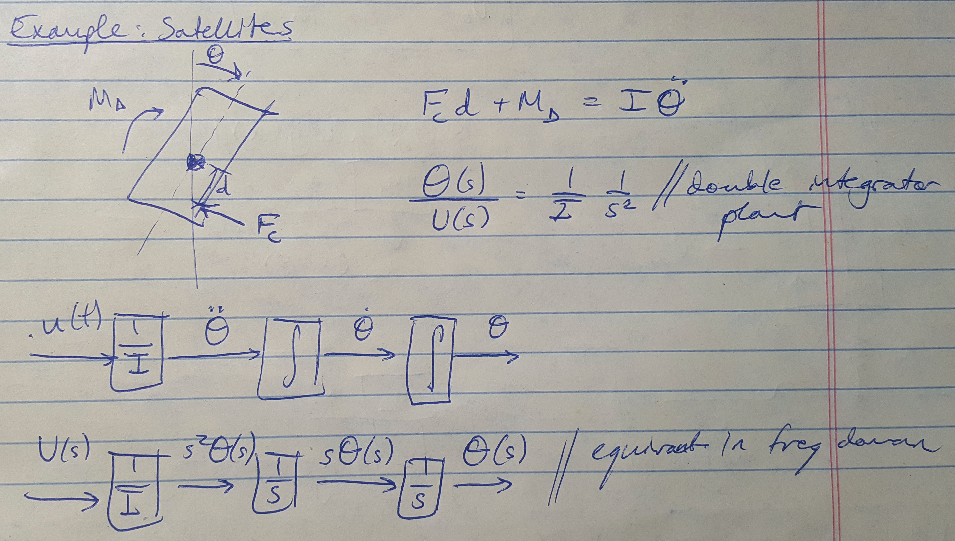

Example 3: Satellite Double-Integrator Plant [1]

This example was a useful review of how 1/s in the frequency domain corresponds to integration in the time domain. We can write the transfer function as a double-integrator plant. The block diagram for this plant shows that we can turn our control input into the acceleration of the plant and then integrate twice to get its position.

Figure 4 - Example 3

Figure 4 - Example 3

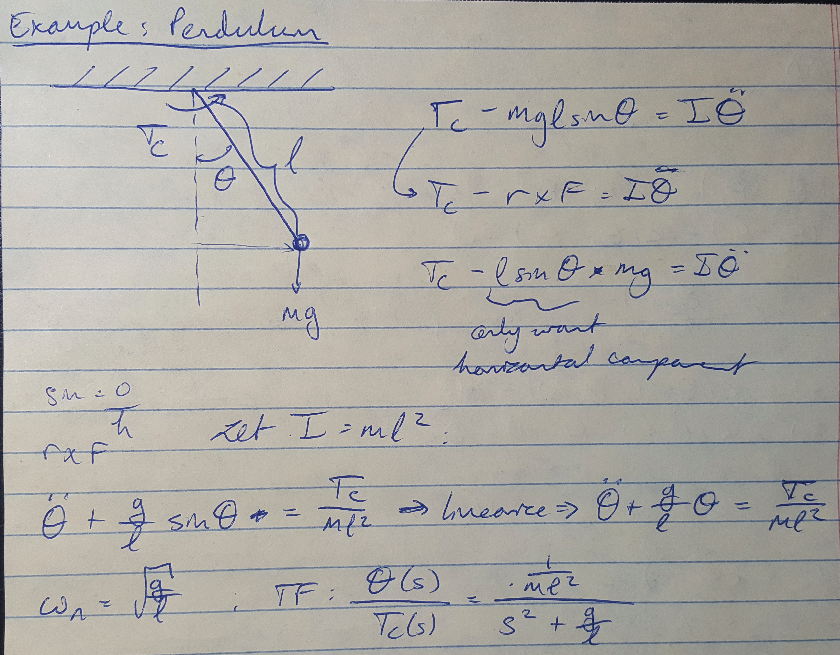

Example 4: Simple Pendulum [1]

This example is not particularly exciting but I wanted to include it because I don’t want to embarrass myself on the exam by not being able to solve it if I am asked to do so. Notice that I linearize the equation here by making a small angle approximation, but I outlined the more rigorous way to linearize an equation in a previous post.

Figure 5 - Example 4

Figure 5 - Example 4

References:

[1] Franklin, G., Powell, J.D., Emami-Naeini, A. Feedback Control of Dynamic Systems, 6th ed. Pearson. 2009.