Tracking and Filtering

Recently I wanted to learn more about how filtering works, and so I am going to spend a little time explaining the theory behind filtering, with a particular focus on Kalman filters and particle filters. I actually would argue that “filtering” is a confusing term to use to describe these tools, because even though we typically use them to track objects in space and time, I usually think of a filter as the thing I put my coffee grounds in every morning. But that’s just me.

Tracking and Filtering

Let’s introduce filtering as the solution to a particular problem that appears in robotics, computer vision and classical control. In these domains, we often want to track the motion of an object over time. We don’t know the object’s exact state (in this context, that means we do not know the object’s exact position, velocity, acceleration, orientation, etc.) but we do have a dynamics model for how the object moves, and we have measurement data [1]. I am going to use my dynamics model and my measurement data to guess what the object’s true state at every time step, and this process is performed by a filter [1].

Filters are solving a problem that we have seen before on this blog. In this problem, we are assuming that we cannot measure the state directly - in other words, we are assuming that it is hidden [2]. We are also going to assume that the process that we are studying is Markovian - that is, we think that the state at the next time step is only going to depend on the state at the current time step and the actions that we take at this time step [2]. Does this sound familiar? We are basically using a filter to track an object inside of a Hidden Markov Model (HMM), which we discussed when we were learning about graph networks [2]. We are also going to assume that the measurements only depend on the current state* and that the model, as well as the object that we are tracking, are going to change continuously and smoothly [2]. Given all of these assumptions, we now have a problem definition that we can begin to solve using probability.

Using Probability to Describe the Filtering Process

A lot of the theory behind filtering depends on probability - we won’t really talk about the filtering algorithm until we get to particle filters, and even then the algorithm description we will look at will rely largely on probability. We can think of a filter as working to make an inference about the hidden state, x, given a set of measurements, z [2]. (We defined “inference” when we were discussing variational autoencoders, see the footnotes). In other words, we are going to use what we know about the system, namely the dynamics model and our measurements, to try to describe the probability density (or the distribution) of state x [2]. Note that I can also call my dynamics model my prediction of the state at the next time step [2].

The filtering process uses two steps to combine the prediction and measurement together [2]. First, we make a prediction about the state of the object at the next time step given the current state and all of the previous measurements [2]. Then the next time step occurs, and we take a measurement at this new time step [2]. Given this new measurement, we compute a correction to the prediction [2]. This correction is a new estimate of the state of the object that is essentially a weighted average of the estimated states from the model and the measurement [2]. This process is illustrated in Figure 1 below. We can see that at time t, we make a prediction about the state at time t+1 [2]. Notice that the prediction itself is a probability distribution of the state [2]. Next, at time t+1, we take a measurement of our object [2]. The measurement is also a distribution, which describes the likelihood that we obtained that measurement value if our state was at x (if that’s confusing, don’t worry, I will go into this in more detail) [2]. Finally, we calculate a corrected prediction of our current state at time t+1, which will be the value of the state at time t+1 that we feed into our prediction for the next iteration of this process [2]. Notice that the corrected prediction has a tighter distribution than both the prediction and the measurement [2]. This is because obtaining more information will always reduce our uncertainty about the true state of the object [2].

Figure 1 - Source [1]

In short, we can say that tracking is a process of “propagating the posterior distribution of the state given measurements across time” [2]. Remember that the posterior distribution is simply the distribution of the current state computed using prior knowledge, such as our measurements. Now let’s dive into some of the details of how we can perform the prediction and correction steps using probability.

Prediction and Correction with Probability

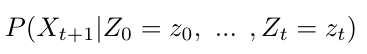

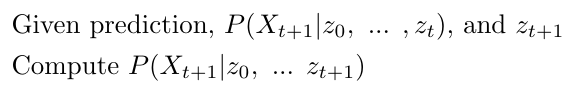

As we discussed above, the tracking (or filtering) process is a two-step process of making predictions and then correcting those predictions about the current state of the object we are following. When we make a prediction, we are making a guess about the value of the state, x, at time t+1, given all of our past measurements up to time t [2]:

Equation 1

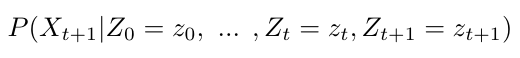

The difference between the prediction and the correction steps is that the goal of the correction step is to make a guess about the value of the state, x, at time t+1, given all of our past measurements as well as the measurement of the current time step, t+1 [2]:

Equation 2

Prediction Step

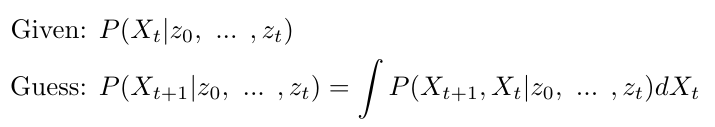

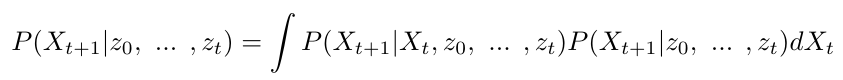

In the prediction step, we have the probability of the state of the current time, t, and we want to compute the distribution of the state at the next time step, t+1 [2]. We can write this as an integral of the joint probability density of the state x at times t and t+1 [2]:

Equation 3

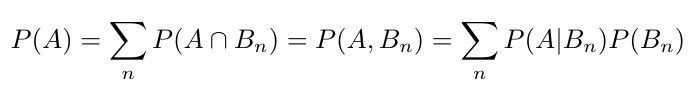

I want to take a brief detour to explain this integral in more detail. This integral is going to calculate the probability of x at time t+1 by adding up the probability that the object will have state x at time t+1 given all possible events at time t - that is, given all possible values of the state x at time t [2]. This integral is applying two concepts from probability: the Law of Total Probability and marginalization [2]. The Law of Total Probability states that we can calculate the total probability of an event, A, by adding up all of the probabilities that A will occur if some set of events, Bn, also occur [2,3]:

Equation 4

The act of marginalizing is to focus on a subset of variables whose probability we are interested in [4]. In this case, we are marginalizing the probabilities of state x at time t+1 given the probability of the state having a value x at time t [4].

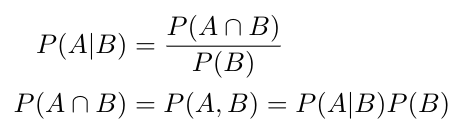

Okay, so now if I have Equation 3 above, I can say that I am conditioning on an event - specifically, I am conditioning the probability of being at state x at time t+1 on the probability of being at state x at time t [2,5]. We already saw the Kolmogorov definition of conditional probability in our discussion of the Law of Total Probability, but just to reiterate, it says that conditional probability allows us to write [5]:

Equation 5

And so now I can use this concept to rewrite my integral in Equation 3 again as follows [2]:

Equation 6

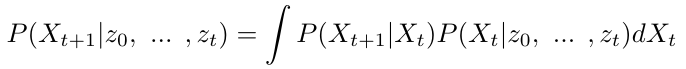

Finally, I can simplify Equation 6 a little more, thanks to my assumptions that I made earlier. Specifically, we assumed that this process is Markovian; that means that my state x at time t+1 only depends on the state at the previous time step and the action that I just took [2]. We have not yet introduced our actions into this paradigm, so that means that my state x at time t+1 only depends on the state at the previous time step [2]. We can call this the independence assumption and it lets us simplify Equation 6 to [2]:

Equation 7

Okay, so now we have an expression for the prediction step. Let’s look at the correction step, which will incorporate our knowledge of the current measurement into this probability distribution [2].

Correction

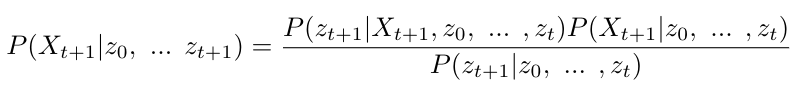

In the correction step, I have a predicted value of x at time t+1, and I want to incorporate my latest measurement, z, taken at time t+1 [2]. Mathematically I can write this below [2]:

Equation 8

Now I’m going to manipulate these equations, first by observing that I can rewrite Equation 8 by applying Bayes’ Rule** [2]:

Equation 9

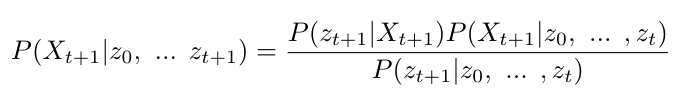

Then we can apply the same independence assumption we described above to simplify the conditional probability of getting measurement z at time t+1 given the state x at time t+1 [2]:

Equation 10

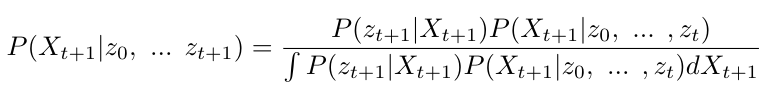

Prof. Bobick points out that we can think of the denominator in Bayes’ rule as a normalizing factor [2]. The probabilities always need to sum to 1, so the denominator is just normalizing all of the probabilities in the numerator so that they will sum to 1 [2]. We can rewrite the denominator again by saying that we can condition the probability of obtaining measurement z at time t+1 on the probability of being at state x at time t+1, as follows [2]:

Equation 11

Notice that we will never actually need to calculate this integral explicitly - this will become more clear as we describe specific approaches to filtering [2]. In fact, I will end this post here and next time, we will talk about the Kalman filter and the particle filter.

Footnotes:

*Making the assumption that the measurement only depends on the current state may not always be a good choice [2]. For example, sensors can sometimes have hysteresis or a delay, which means that the reading you get at a current time, t, represents what the system looked like a couple time steps ago [2]. (Think of how the bathroom scale has to settle down when you step on it before you can get a good reading on your weight.)

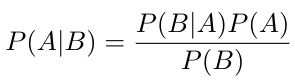

**Prof. Bobick jokes that you should get Bayes’ rule tattooed on your foot, and I’m starting to agree with him…anyway, here’s the formula again in case you need it [2]:

Equation 12

References:

[1] Bobick, A. “Lesson 42: 7A-L1 Introduction to tracking.” Introduction to Computer Vision. Udacity. https://classroom.udacity.com/courses/ud810/lessons/3260618540/concepts/32740285460923 Visited 13 May 2020.

[2] Bobick, A. “Lesson 43: 7B-L1 Tracking as inference.” Introduction to Computer Vision. Udacity. https://classroom.udacity.com/courses/ud810/lessons/3271928538/concepts/32865685440923 Visited 13 May 2020.

[3] Wikipedia. “Law of total probability.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Law_of_total_probability Visited 14 May 2020.

[4] Wikipedia. “Marginal distribution.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marginal_distribution Visited 14 May 2020.

[5] Wikipedia. “Conditional probability.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conditional_probability Visited 14 May 2020.