Probability and Graph Networks

In my previous post, I presented the motivation for graph networks as described by a paper by DeepMind that I have been reading [1]. We have covered the ideas of relational inductive bias and combinatorial generalization, which describe how we, as humans, think. The DeepMind paper argues that using graph networks to think like humans can help us solve some key challenges, such as (1) complex language/scene understanding, (2) reasoning about structured data, (3) transferring learning beyond training conditions and (4) learning from small amounts of data/experience [1]. In this post, I want to introduce the basic structure of a graph network and some of the probability concepts that make them work. Specifically, we will discuss the concepts of joint probability distributions and conditional independence. Let’s get started.

Fundamental Definitions of a Graph

The DeepMind paper introduces a formal definition of a graph using the following terms [1]:

(1) Structure: an arrangement of known elements. A “structured representation” displays this structure, and a “structured computation” operates over all of the elements in the structure and the structure as a whole.

(2) Entity: this is an object, represented by a node in the graph. It has some attributes, like weight or size or color.

(3) Relation: this is a property that connects two entities, or nodes, together. It can also have attributes, such as “A is 10 times heavier than B.” A relation’s attributes can also depend on the global context; for example, a stone and a feather will have different accelerations depending on what medium they are falling through.

(4) Rule: this is a function that maps entities and relations to other entities and relations. These functions usually take in one to two arguments and return a single property value - for instance, they can tell you if A is large relative to B.

(5) Relational reasoning: this describes the process we use to operate on a structured representation of entities and relations using a set of rules.

A graph is a structure that contains entities and relations, and can be reasoned about using rules. The DeepMind paper gave an interesting interpretation of this graph network using probability - they said that graphs can represent joint distributions by explicitly knowing the conditional independences between variables [1]. But what does this mean? I am going to unpack the terms joint probability distribution and conditional independence to answer that.

Joint Probability Distributions and Conditional Independence

A joint probability distribution describes the probability that two or more random variables will occur at the same time [2]. It is a way of describing the relationships between variables [2]. A joint probability density function will describe all of the possible combinations of two random variables, assuming that they are continuous [2].

What about conditional independence? Let’s say we have two random events, A and B, and a third random event, C [3]. The events A and B are conditionally independent if, given C, then A is independent of B [3]. In other words, if we know that C has occurred, then knowing that A occurred will not tell us anything new about whether or not B will occur [3]. Huh? Let’s think through an example: Fatima and Jorge work in different parts of Pittsburgh, and they are both trying to get home at the end of the day [3]. In addition to working in different parts of Pittsburgh, they also live in completely different neighborhoods [3]. We want to know how likely it is that Fatima and Jorge will get home on time if it is raining in Pittsburgh (events A and B) [3]. We know that if it is raining (event C) then Fatima and Jorge are more likely to get home late [3]. But if we know that Fatima gets home late (event A), does that tell us anything more about how likely it is that Jorge will be late (event B)? No, it does not, because Fatima’s commute is completely independent of Jorge’s [3]. We would say that Fatima and Jorge’s respective arrivals at home are conditionally independent, given knowledge of the weather in Pittsburgh [3].

So basically, graph networks are capable of describing the likelihood of many different events occurring (their joint probability distributions) by explicitly knowing the likelihood of each event occurring given knowledge of the other events (their conditional independences) [1]. This is useful because being able to capture joint probability distributions using conditional independences accurately “captures the sparse structure which underlies many real-world generative processes” [1]. In other words, thinking about joint probability distributions and conditional independences is representative of how the world really works, so this approach ensures that graph networks are more likely to be able to accurately represent real-world phenomena.

Let me elaborate on this point a little more by introducing an example of a model that can represent joint probability distributions using conditional independence: a hidden Markov model [1]. A hidden Markov model is a statistical model of a Markov process [4]. I know, I know, that doesn’t help. Well, a statistical model is one that makes assumptions about how the data in a sample was generated, as well as, by extension, how the data was generated for the larger population from which the sample was taken [5]. A statistical model is an “idealized representation of the data-generating process” [5]. And a Markov process, or model, is a random model that represents changing systems [6]. What is special about a Markov process is that we assume that the next state is only dependent on the current state, not on previous states [6]. This assumption is very powerful, and allows us to do a lot of things with this model that we could not do with models that require knowledge of the history of the system [6].

Okay, so a hidden Markov model (HMM) is a statistical model of a Markov process, but how does it work? We use a HMM to learn about a process, X, by observing Y [4]. This is useful in situations where you cannot observe the state of X directly, but you can observe the process Y, which is related to X [4]. At every moment in time, the conditional probability of Y at that moment, given the history of X, must not depend on anything but the current state of X [4]. Doesn’t this sound like a conditional independence situation? We want to know the joint probability of Y and X, based on the assumption that there is some conditional dependence of Y on X, given our knowledge of the history of X.

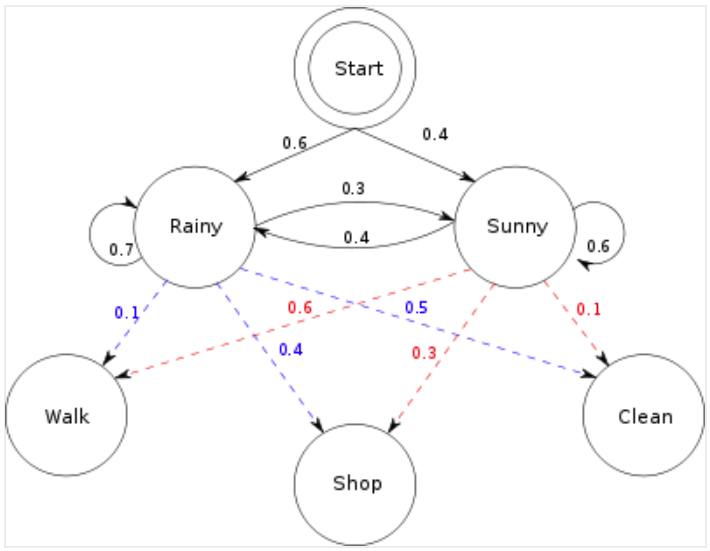

Let me give another example with Jorge and Fatima. Jorge and Fatima are friends and they talk every day [4]. Every day, Fatima tells Jorge if she went for a walk, went shopping or cleaned her apartment, and her decision of what activity to pursue is driven by the weather [4]. Jorge only knows that, in general, it is either sunny or raining, but he does not know the exact weather patterns every day [4]. Since he cannot observe the weather directly, Jorge must guess what the weather is based on what he knows about Fatima’s daily activities [4]. This is captured in Figure 1 below. In this situation, we are modeling the joint probability distribution of different weather events by explicitly considering the conditional independence of Fatima’s daily activities. Such a model can be solved using different approaches, one of which is called the Viterbi algorithm [4].*

Figure 1 - Source [7]

We can think of a graph as representing joint probability distributions using conditional independence, and this is useful because it agrees well with how events are related in the real world [1]. The DeepMind paper argues that reasoning about these “sparse dependencies between random variables” is an efficient computational approach [1]. In my next post, I will discuss some of the unique properties of graphs that make them useful tools for representing these real-world processes.

Footnotes:

*The Viterbi algorithm is a dynamic programming algorithm that looks for the most likely set of hidden states that resulted in the sequence of observed states [8].

References:

[1] P. W. Battaglia et al., “Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks,” Jun. 2018. ArXiv ID: 1806.01261. https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.01261

[2] Stephanie. “Joint Probability Distribution.” Statistics How To. https://www.statisticshowto.com/joint-probability-distribution/ Visited 08 May 2020.

[3] Wikipedia. “Conditional independence.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conditional_independence Visited 08 May 2020.

[4] Wikipedia. “Hidden Markov model.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hidden_Markov_model Visited 08 May 2020.

[5] Wikipedia. “Statistical model.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Statistical_model Visited 08 May 2020.

[6] Wikipedia. “Markov model.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Markov_model Visited 08 May 2020.

[7] Terencehonles. “Hidden Markov model.” Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HMMGraph.svg Visited 12 May 2020.

[8] Wikipedia. “Viterbi algorithm.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viterbi_algorithm#Example Visited 08 May 2020.