Introduction to Graph Networks

Whew! That run of posts on variational autoencoders was fun! The reason I wanted to investigate them in detail is because I want to understand how they can be used in conjunction with graphs, instead of single data points. In fact, I want to understand in general how neural networks can be used to process graphs as inputs, instead of scalar or vector values. This is a rich area of research and I thought I would start by reading an excellent review/position paper by a group of researchers at DeepMind [1]. In this post (and possibly a few more, this paper was really long), I am going to discuss some of the basic concepts behind graph networks. Let’s dive in!

Why Should I Care About Graphs?

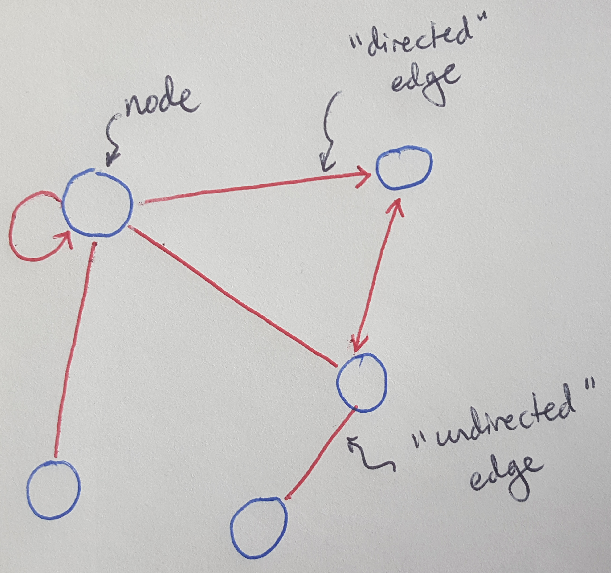

So far I have only written about neural networks that take in scalars or vectors of data - basically, everything I have done so far uses data that comes in a matrix. Graphs are in some ways a richer representation of data than you can get in a single matrix. Consider Figure 1 below. Graphs consist of nodes that are connected by edges. If the edges have a direction - if they are showing the flow of information from one node to another - then we say that the graph is a directed graph [2]. An example of this kind of graph could be the representation of a neural network that we’ve seen before where each note computes a value that is sent along an edge to the next node in the next layer of the neural network. Note that the edge can indicate motion in one direction or two [2]. Conversely, if the edges do not have a direction, then we say that we have an undirected graph [2]. This might be the kind of graph we use to represent a chemical compound - if each node represents a molecule, like hydrogen or carbon, then each edge represents the chemical bond between them. The chemical bond does not “flow” in either direction, it simply links the two molecules together.

Figure 1

Okay, so graphs can show relationships between nodes, but why is that useful? Graphs can be used to represent lots of different systems we find in the real world - anything from social networks to robots [3]. There is exciting research coming out that applies all of the tools we have developed to machine learning and reinforcement learning to graphs. In essence, all of the learning tools that we developed for data that can be represented by matrices (like photographs or your Netflix viewing history) can now also be applied to systems, as represented by graphs. Moreover, graphs are very powerful because they are a simple but accurate representation of how we, as humans, reason about the world around us [1]. Let’s discuss this idea in more detail.

Human Thinking Uses Relational Inductive Biases and Combinatorial Generalization

The central argument to the DeepMind paper [1] is that we can use graphs to teach artificial intelligence (AI) to think more like humans. Specifically, the paper explains that we as humans are able to generalize beyond our own experiences [1]. For example, if we know that tennis balls tend to bounce when they hit a solid surface like the floor or a wall, we can easily imagine what would happen if you dropped an entire bag of tennis balls onto the floor of a tennis court, even if we have never seen that happen in real life. The DeepMind paper introduces this concept of “relational inductive biases,” which is a term describing the bias that we have as humans which drives us to think of things in terms of objects (like tennis balls), their relations (how close they are to each other and the floor) and the rules that govern how these objects move (a tennis ball will bounce when it hits a hard surface) [1]. More formally, the paper defines relational inductive biases as “inductive biases which impose constraints on relationships and interactions among entities in a learning process” [1].

So if we as humans are able to think in terms of these three things - objects, relations and rules - why is that so powerful? Our ability to think in terms of objects, relations and rules enables us to make predictions about new situations that we have never seen before [1]. The DeepMind paper says that we are capable of “combinatorial generalization,” which is essentially a fancy way of saying that we can build up a prediction using these building blocks of known objects, relations and rules [1]. Returning to the tennis ball example, I have never seen a bag full of tennis balls dropped onto the floor of a tennis court, but I know what tennis balls are, I know that they balls bounce, that they only change direction when they hit a solid surface, and I know that they tend to accelerate as they fall. Given all of these facts, I can easily imagine that the balls would fall out of the bag, and bounce up and down on the tennis court floor until they eventually ran out of kinetic energy and came to rest, scattered randomly about on the floor. This thought experiment is an example of our ability to perform combinatorial generalization [1]. And yet, as easy as it is for me to perform this thought experiment, it is very difficult to teach a computer to do it.

Figure 2 - Source [4]

I just quickly want to take a detour to discuss what inductive biases are, because that helped me to wrap my head around this concept. An inductive bias is a set of assumptions that we make to help us predict how an agent is going to behave when we have never seen it before [5]. There are many examples of inductive biases out there - a classic example is Occam’s Razor, which states that it is good practice in scientific research to start with the simplest hypothesis, because simple hypotheses are easy to test [6].* This assumption - that we should begin with a simple hypothesis when studying an unknown scientific phenomenon - biases us towards simple explanations.** The assumption is encouraging us to think and learn in a particular way. I found this confusing at first because I typically think of bias as a bad thing - it prevents us from being completely open minded because our bias is forcing us to think a certain way. But the DeepMind paper argues that this bias is actually very powerful, because if we choose the right kind of bias, we can actually improve our ability to learn about new environments more rapidly than if we had no bias at all [1].

In fact, this tension between thinking with and without an inductive bias has actually played out over the history of the development of AI [1]. In the early days of AI research, computing resources were very expensive, and so scientists built structure into their models to add complexity without adding to the computational time for that model [1]. In essence, by adding structure to the models, these scientists were adding a strong inductive bias to how the model would make predictions given new inputs [1]. However, in more recent work where computing power has become very cheap and we have huge amounts of data at our disposal, there has been a trend among researchers to impose little or no structure on the data, because we don’t need to - we will be able to perform huge numbers of computations over our raw data very quickly [1]. There has been no penalty for this highly flexible approach because, even though we get less knowledge out of each data point, we have tons of data and tons of computing power to process it. This approach has even been shown to work in linguistic modeling, where of course there is a strong underlying structure to language applied by grammar [1]. Ultimately, the DeepMind paper argues that, to best teach AI to think like a human, we should be introducing some structure, some relational inductive biases, because we as humans have these same biases [1]. At the same time, having some flexibility to our learning approach will allow us to adapt our models to novel inputs that we have never seen before [1]. In short, we should merge the flexible and structured approaches to learning to get the best results [1].

How Will Graphs Help AI to Think Like a Human?

Okay, so if I agree with DeepMind that we need to teach AI to think in terms of objects, relations and rules, and learn to combine them together to make predictions given novel inputs, how do I actually do that in practice? This is where graphs come in. The DeepMind paper argues that the crucial power to using graphs in AI is that they allow us to “compute over discrete entities and the relations between them” [1]. Why? Because the nodes of the graph represent entities, and the edges on a graph represent the relations that link those entities together. When we use the graph network in a learning setting - for example, with neural networks and all the tools that we have for them, like backpropagation - then the graph network will learn how to best represent and structure the entities and their relations [1]. This is important - instead of “hand engineering” the graphs ourselves, we are simply going to introduce a light inductive bias that tells the network that it must represent the data as a graph, but how that structure is formed is up to the network to learn on its own [1]. This is how we will merge our flexible and structured approaches to teach AI to think like a human.

Next Steps

In my next post, I am going to introduce some of the key elements of a graph network (per DeepMind) in more detail, as well as some of the concepts of probability that we will need to understand how they work. Finally, we will discuss the mathematics that govern how a graph network actually learns.

Footnotes:

*The English Franciscan friar, William of Ockham, is credited with defining this particular inductive bias. His exact words are: “Entities should not be multiplied without necessity.” [6]

**There are many other examples of inductive bias out there. Some examples just from machine learning include [5]:

(1) Max conditional independence: if the hypothesis can be represented using a Bayesian approach, then try to maximize the conditional independence.

(2) Minimum cross-validation error: if you’re trying to choose between hypotheses, pick the one with the lowest cross-validation error. (We used this in our discussion of bias and variance!)

(3) Maximum margin: when drawing the boundary between two classes, try to maximize the width of the boundary - it assumes that distinct classes are separated by big boundaries in the first place. This is used in support vector machines.

(4) Minimum description length: when forming a hypothesis, try to minimize the length of the description of the hypothesis, because shorter hypotheses are more likely to be true (Occam’s razor).

(5) Minimum features: only use features if they clearly improve the outcome.

(6) Nearest neighbors: assume that data points in a small region of the feature space (latent space) belong to the same class. Used in k-nearest neighbors algorithm to assume that if you get a data point whose class you don’t know, then you should assume that it belongs in the same class as the data points that it is closest to.

References:

[1] P. W. Battaglia et al., “Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks,” Jun. 2018. ArXiv ID: 1806.01261. https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.01261

[2] Anand, R. “An Illustrated Guide to Graph Neural Networks.” dair.ai on Medium. 30 Mar 2020. https://medium.com/dair-ai/an-illustrated-guide-to-graph-neural-networks-d5564a551783 Visited 08 May 2020.

[3] Karagiannakos, S. “Graph Neural Networks: An overview.” AI Summer. 01 Feb 2020. https://theaisummer.com/Graph_Neural_Networks/ Visited 08 May 2020.

[4] Giphy. “Dog Tennis GIF.” https://giphy.com/gifs/dog-black-mp7lPwpEOCZ7G Visited 12 May 2020.

[5] Wikipedia. “Inductive bias.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inductive_bias Visited 08 May 2020.

[6] Wikipedia. “Occam’s razor.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occam%27s_razor Visited 08 May 2020.