Git with the Flow

In a previous post I discussed the basics of using git locally and remotely, and today I am going to extend that discussion to two popular workflows for teams that use git. I will also cover some best practices for using git.

The two workflows that we will discuss today differ by what kind of product they are used to develop. For example, the first (and older) workflow is git-flow, and it was developed to track software that had explicit release versions [1-3]. As software development evolved, git was used to track codebases that were continuously released to the customer (this is how most web applications work*) [1-2]. In this case, a new workflow was developed by GitHub, and hence called Github-flow, to manage continuously released software [1-2]. I am partial to using git-flow because I am focusing on writing code that I would like to release in an open-source format to the scientific community, and I anticipate only releasing a codebase a couple of times. As a researcher, I do not expect to be continuously improving and supporting the codebase associated with a particular publication for years after it is released. However, your needs and use paradigm will probably differ.

Let’s start by discussing git-flow, and then discuss the changes that Github-flow made to that basic structure. We will end this post by reviewing some more best practices that I did not cover previously.

Git-flow

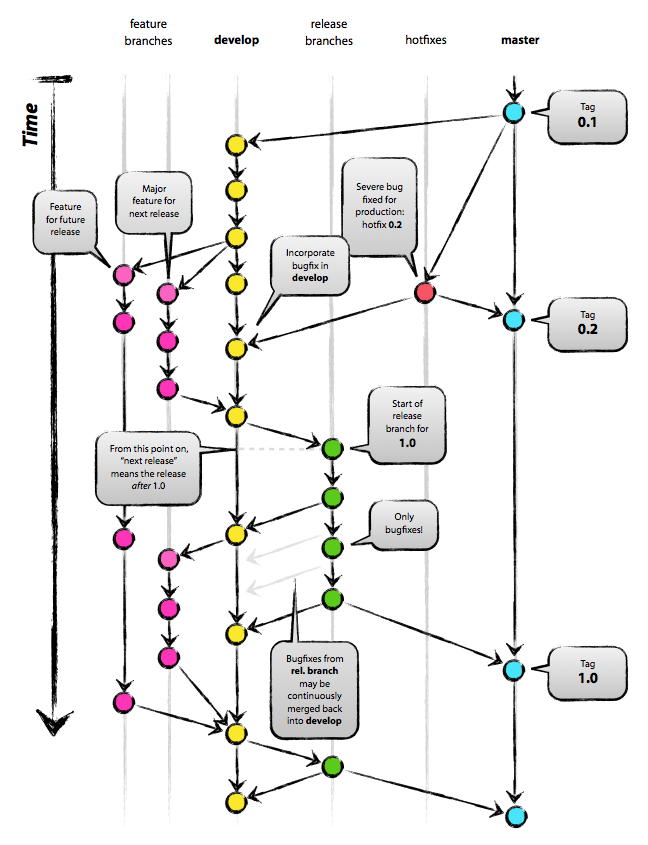

This workflow was first formally introduced by Vincent Driessen in [3], and I recommend that you look at his post for more detailed explanations of how to perform git-flow tasks in the command line. The workflow centers on using branches within git for different purposes. Branches are copies of the codebase that are still tracked in the same repository, but contain different features. We will go through each type of branch used in git-flow in detail. These different branches (and how they are related) are shown in Figure 1. Only the master and development branches must exist for the lifetime of the project. In git-flow, we are also allowed three types of branches that only exist for a limited period of time: features, release and hot-fix branches exist long enough to complete a specific task [3]. The key takeaway is that, as a coder, you should only ever be concerned about the master and development branches, and whatever feature/hot-fix/release branch you are currently working on.

Figure 1 (Source [1])

Master Branch

In git-flow, we always start with a master branch [1],[3]. This branch contains only the released versions of the code, and should exist for the entire lifetime of the codebase [3]. The master branch codebase contains all the code from the last major release.

Development Branch

From the master branch, we create a second development branch, which must always contain production-ready code [1],[3]. The development branch may have new features that have not yet been released to the customer - the codebase is the same but with changes and improvements made to it. Any of the branch types (feature, release or hot-fix) must be checked out from the current commit in the development branch and they must be merged back to the development branch when they have been completed [1],[3]. Once the branches have been merged back to the development branch, they should be deleted to clean up the repo [3]. (Don’t worry, git will still contain a record of that branch and its commits.)

Note: When one of these other branch types are merged back to the development branch, use the command $ git merge –no-ff myfeature where myfeature is your feature branch [3]. The –no-ff flag tells git not to fast-forward the development branch to the state of the feature branch, and forces it instead to create a new commit that introduces myfeature into the development branch [3]. This is preferable because then if the new feature is not working, we can simply revert to the previous commit before it was introduced [3].

Feature Branches

Feature branches are used to add new features to the codebase [1],[3]. The feature can be planned to be added to the next release, or to some release in the distant future [1],[3]. Often a the coder who owns the feature branch will work on it locally but will not push it to the remote repo [3]. Separate feature branches allow you to develop and test one additional feature at a time before merging it back to the development branch. In other words, if you experiment in feature branches, you will never be in danger of breaking your working codebase! (Assuming that you are following the rule that the development branch is always production-ready, see above.)

Release Branches

Release branches are for preparing the codebase for a new production release [3]. They should only be used to fix minor bugs and prepare the meta-data for a new release, they should not contain anything more substantive than that [3]. The new production release number should also be assigned when the release branch is checked out from the development branch [3]. When the release branch is ready, it should be merged to both the master branch and the development branch [3]. After merging to the master branch, use the command $ git tag -a 1.2 to tag the new commit with the new release number [3].

Hot-fix Branches

These branches are for fixing urgent bugs in the code that are affecting the current production release [1],[3]. Notice that, unlike feature branches, hot-fix branches are merged directly to the master branch because hot-fixes should only be used to repair bugs in the production release [3]. The idea is that the rest of the team can continue to work on the development branch while someone is using the hot-fix branch to repair the bug in the master branch. When the hot-fix is ready for release, the production release number is incremented (from, for example, 1.2 to 1.2.1) [3]. The hot-fix branch is merged with both the master branch and the development branch (since presumably the bug exists in the development branch too) [3]. Note that if a release branch is also currently in use (say that the team was about to issue a new production release when it found the critical bug), then the hot-fix branch should be merged with the release branch too [3].

Github-flow

Now that we have learned about git-flow, what are the differences between git-flow and github-flow? Scott Chacon argues that github-flow is simpler than git-flow, partly because it does not have separate development and master branches [2]. Github-flow centers around the master branch, which is always ready to be deployed (released) [2]. There is no development branch and there are also no separate categories of short-term branches like release branches or hot-fix branches. Instead, new work of any kind is branched from the master branch and given a descriptive name of some kind [2]. When this new branch is ready to merge, the coder in charge of that branch opens a pull request to the master branch [2]. The pull request is an excellent tool for signalling to your team that you have a contribution ready to share or debug with the team, and you want their feedback on it [1-2]. Once the contribution has been reviewed, it is merged into the master branch and the code in the master branch is then deployed immediately [2].

Other Best Practices

Finally, I would like to close out this post by listing some best practices that we can follow as we use git, regardless of the workflow we have adopted.

Commit Often

The basic philosophy here should be that each commit to the repository should do one thing [1]. If a commit contains too many changes, it will be difficult to keep track of them and find the one change that broke the codebase [1]. Similarly, do not use $ git add . because that will move all files that you have changed since the last commit into the staging area [1]. You want to focus your commits and therefore you should manually add the files that were changed in the same way [1].

Minimum Viable Pull Requests

Similar to the philosophy of pushing commits that only change one thing, your pull requests should also be kept simple and straightforward [1]. For example, if you want to make a significant change to the codebase, and you are using a feature branch to contain the work, initiate a pull request when you build some of the prerequisites for the feature [1]. This will allow your team to review the foundation of your new feature and merge it into the development branch while you are finishing your feature branch [1]. Then when you initiate the pull request for the completed feature branch, your team is already familiar with your work and has had time to review its preliminary features [1].

Pull Changes from Development to Feature Branches Often

As you are working on feature branches, it’s likely that the development branch is also being updated by your teammates. To compensate for this, make sure you periodically pull the changes from the development branch to your feature branch and incorporate them into your work [1]. This will make it easier for your feature branch to merge with the development branch when it is ready.

This concludes my 2-post series on the fundamentals of using git. I hope that as I continue to use it that I will learn more, and I welcome your comments and suggestions as well.

*As a side note, some of Paul Graham’s essays on his webpage and in his book, Hackers and Painters, discuss the benefits of working on web-based applications. He was one of the pioneers of the approach when he led a startup during the dot-com boom that eventually became Yahoo! Store.

References:

[1] Hileman, J. “Changing history, or How to Git pretty.” 3 November 2011. http://justinhileman.info/article/changing-history/ Visited 03/20/2020.

[2] Chacon, S. “GitHub Flow.” 31 August, 2011. http://scottchacon.com/2011/08/31/github-flow.html Visited 03/20/2020.

[3] Driessen, V. “A successful Git branching model.” 5 January, 2010. https://nvie.com/posts/a-successful-git-branching-model/ Visited 03/20/2020.