Heaps

Welcome back to another blog post about computer science fundamentals. Today I’m writing about heaps, with a focus on binary heaps and min-heaps. Heaps started out as an amorphous, nebulous concept in my mind - I wasn’t really sure what they were, and they were confusing because they looked like trees and graphs and I didn’t know why they were considered a separate category. I’m going to try to make clear the distinction of heaps as a unique data structure with specific applications today. And as always, if you want to see an implementation of min-heaps in code, please take a look here at work based on a tutorial by [1].

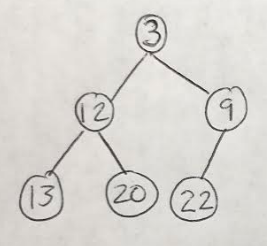

Heaps are a specific subset of graphs, where the nodes are ordered according to their values. The heaps we will discuss today are called binary heaps because their structure is that of a complete, binary tree [2]. We are also going to focus on min-heaps, where the nodes of the tree are organized in ascending order, i.e. where the root node has the smallest value of all the nodes in the heap [2]. An example of a min-heap is shown in Figure 1. Notice that there is no required ordering of nodes in the same level of the min-heap; for example, in Figure 1, the node with value 12 is to the left of the node of value 9, but on the next level down 13 is to the left of 20 [2].

Figure 1

In his post on heaps in Python, Moshe Zadka makes the interesting distinction that heaps are frequently used as the concrete data structure that implements the priority queue, which is an abstract data structure [3]. To quote him directly, Zadka says that “[a]n abstract data structure determines the interface, while a concrete data structure defines the implementation” [3]. In this case, the priority queue abstract data structure is used to arrange items according to their priority [3]. For example, a priority queue could be used to schedule when to send e-mails, or merge log files together [3]. This is a somewhat abstract task until you define the min-heap, where we know that the data structure will use the value of the nodes in the heap to arrange them in order - for example, according to an importance rating for different e-mails, or the time stamps on log files [3].

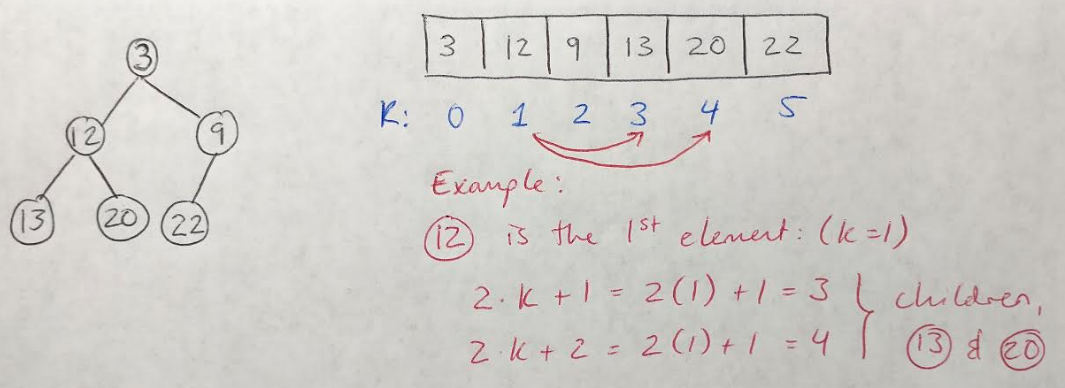

Let’s take a look at how we could implement a min-heap in Python to understand them a bit better. One way to do this is to store the min-heap in a list, where the arrangement of all the elements in the list corresponds to their position in the min-heap [3]. For example, if we choose a random element, k, in the list, then we can say that [3]:

- The first child of k is 2 x k + 1

- The second child of k is 2 x k + 2

- The parent of k is (k - 1) / 2

Figure 2

This idea is also illustrated in Figure 2 to help clarify. Note that we would need to check that the indices of the children do not exceed the size of the list - if they did, that would indicate that the element k had fewer than 2 children [3].

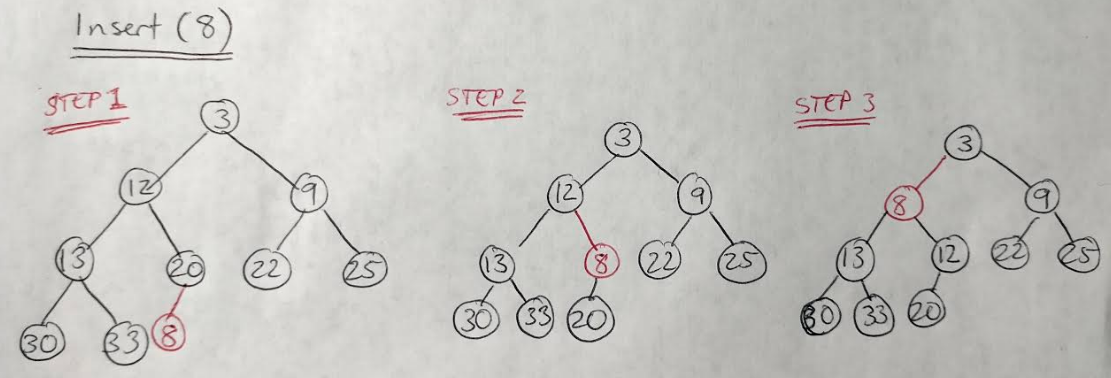

One benefit to defining a concrete data structure for implementing an abstract data structure, is that the concrete definition allows you to calculate the runtime and memory efficiencies of the data structure and its associated methods [3]. For example, let’s consider the insert(element) method for a min-heap, which works like this [2], and is also shown in Figure 3:

- Insert the element at the bottom right of the min-heap (above the largest value in the min-heap).

- Compare the value of this new element with its parent. If the new element is smaller than its parent, then they should swap places.

- Repeat the swapping process (also referred to as “bubbling up”) until the element is larger than its parent.

Figure 3

Since the min-heap is a binary tree, we know that its height is equal to the base-2 logarithm of n, where n is the number of nodes in the tree. And since, in the worst case, the inserted element would need to bubble up all the way to the root, we can say that the running time of the insert operation is O(log n) [2].

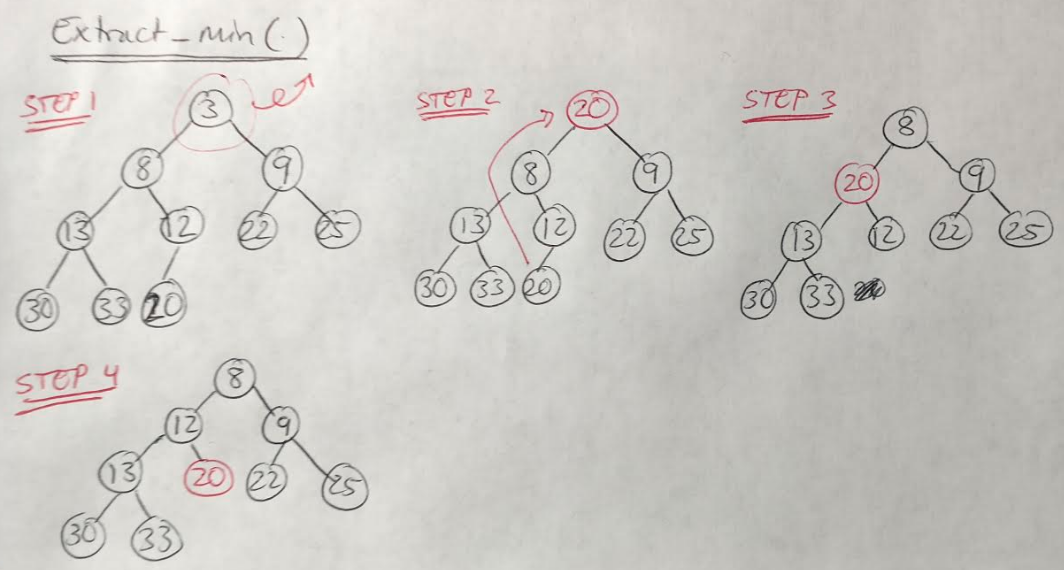

Let’s take a look at another fundamental operation for min-heaps, called extract_min [2]. This operation removes the minimum value, which is easy, since the minimum value is always the root node, by definition [2]. But we also need to take a few more steps to replace the root [2]:

- Remove the minimum element.

- Move the bottom right-most element in the heap to the root position.

- “Bubble down” the element in the root position by comparing it against its children and swapping if it is larger than one of them.

- Repeat this process until the min-heap structure has been restored.

Figure 4

Notice that, in Figure 4, we always swapped the node of value 20 with the smaller of its two children, i.e. with node of value 8 instead of node of value 9 [2]. The extract_min() method also takes O(log n) time for the same reason as for the insert() operation [2].

I think that’s all I have to say about heaps at this time. Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for some new posts on basic sorting and graph traversal algorithms, coming soon.

References:

[1] Erick. “Heap implementation in Python.” Edpresso. https://www.educative.io/edpresso/heap-implementation-in-python Visited 23 Jan 2021.

[2] Laakmann McDowell, G. Cracking the Coding Interview, 6th edition. 2016. CareerCup, LLC.

[3] Zadka, M. “The Python heapq Module: Using Heaps and Priority Queues.” 24 Jun 2020. https://realpython.com/python-heapq-module/ Visited 23 Jan 2021.