Getting Some Intuition for Matrix Exponentials

In a recent post, we talked about some fundamental mathematical operations presented in a robotics textbook written by Murray, Li and Sastry. One of these operations was a matrix exponential, which was unfamiliar to me. It turns out that matrix exponentials are a really cool idea that appear in lots of fields of science and engineering. Thanks to a fabulous video by 3Blue1Brown [1], I am going to present some of the basic concepts behind matrix exponentials and why they are useful in robotics when we are writing down the kinematics and dynamics of a robot.

In MLS, the authors explain that matrix exponentials are useful for “map[ping] a twist into the corresponding screw motion” [2]. Recall that a twist is infinitesimally small and the screw contains the full magnitude of the motion [2]. Another way to say this is that the matrix exponential can encode a rotation as a function of the direction of rotation and the angle of rotation [2]. I will explain this in more detail in this post.

Basic Definition of a Matrix Exponential

A matrix exponential is related to the simpler concept of raising the number e to a real number exponent. We can write this operation as an infinite sum [1]:

\[e^x = x^0 + x^1 + \frac{1}{2}x^2 + \frac{1}{6}x^3 + … + \frac{1}{n!}x^n + …\]Notice that this expression is a Taylor series. The sum of the Taylor series approaches the value of \(e^x\) [1].

A matrix exponential is, in a sense, an extension of this idea, using matrices as input \(x\) instead of real numbers. For example, I can rewrite the expression above with \(x = \left[ \matrix{1 & 2 \cr 3 & 4} \right]\) [1]:

\[e^{\left[ \matrix{1 & 2 \cr 3 & 4} \right]} = \left[ \matrix{1 & 2 \cr 3 & 4} \right]^0 + \left[ \matrix{1 & 2 \cr 3 & 4} \right]^1 + \frac{1}{2}\left[ \matrix{1 & 2 \cr 3 & 4} \right]^2 + \frac{1}{6}\left[ \matrix{1 & 2 \cr 3 & 4} \right]^3 + …\]This still makes sense because I can raise matrices to a real number power by multiplying the matrix by itself n times. And in general, this infinite series will always approach a stable value - in this case, a stable matrix [1].

The matrix exponential is useful in mathematics when we are trying to solve a system of differential equations. For example, let’s say I want to find expressions for \(x(t)\), \(y(t)\) and \(z(t)\) given the equations below [1]:

\(\frac{dx}{dt} = a \cdot x(t) + b \cdot y(t) + c \cdot z(t)\)

\(\frac{dy}{dt} = d \cdot x(t) + e \cdot y(t) + f \cdot z(t)\)

\(\frac{dz}{dt} = g \cdot x(t) + h \cdot y(t) + i \cdot z(t)\)

I can use a matrix exponential to find the coefficients of the functions [1]:

\[e^{\left[ \matrix{a & b & c \cr d & e & f \cr g & h & i} \right]t}\]More generally, if I have a system of equations \(X(t)\) and a matrix of coefficients \(M\) then I can solve the following differential equation written in terms of linear algebra to find expressions for all the functions contained in \(X(t)\) [1]:

\[\frac{d}{dt}X(t) = MX(t)\]Remembering e and Its Derivative

There is another expression that looks remarkably similar to the one shown just above. Specifically, the derivative of \(e\) has the same form as the equation that can be used to solve a system of differential equations [1]:

\[\frac{d}{dt}e^{rt} = re^{rt}\](Keep in mind that we need to also take into account initial conditions if we want to find the solution to a specific system of equations [1].)

Bringing it all together, it can be shown (check out the last part of [1]) that the derivative of the matrix exponential follows the same form as the derivative of e when raised to a real number, that is [1]:

\[\frac{d}{dt} e^{Mt} X_0 = M \big( e^{Mt} X_0 \big)\]Showing that the Definition of a Matrix Exponential is Correct

Let’s take a simple example of how the matrix exponential is used to encode rotations, which we mentioned earlier is one of the reasons why they are so useful in robot kinematics. When we find a matrix that correctly encodes a given rotation, we will see that it is typically a skew-symmetric matrix which can be used to convert between screws and twists [2].

Consider the matrix, \(\left[ \matrix{0 & -1 \cr 1 & 0} \right]\). This matrix is a solution to the following system of equations [1]:

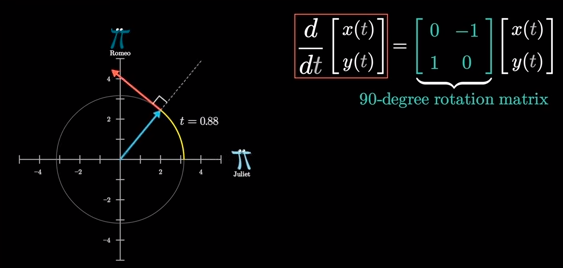

\[\frac{d}{dt} \left[ \matrix{x(t) \cr y(t)} \right] = \left[ \matrix{0 & -1 \cr 1 & 0} \right] \left[ \matrix{x(t) \cr y(t)} \right]\]Geometrically, this expression indicates that the rate of change of \(\left[ \matrix{x(t) \cr y(t)} \right]\) is tangent to the direction of \(\left[ \matrix{x(t) \cr y(t)} \right]\) and has the same magnitude (this is shown in Figure 1) [1].

Figure 1 - Source [1]

But mathematically, why does this make sense? If we compute the Taylor series of \(e^{\left[ \matrix{0 & -1 \cr 1 & 0} \right]t}\), we will find that each term in the matrix becomes an infinite sum with a specific pattern as follows [1]:

\[e^{\left[ \matrix{0 & -1 \cr 1 & 0} \right] t} = \left[ \matrix{ 1 - \frac{t^2}{2!} + \frac{t^4}{4!} - \frac{t^6}{6!} + … & -t + \frac{t^3}{3!} - \frac{t^5}{5!} + \frac{t^7}{7!} - … \cr t - \frac{t^3}{3!} + \frac{t^5}{5!} - \frac{t^7}{7!} + … & 1 - \frac{t^2}{2!} + \frac{t^4}{4!} - \frac{t^6}{6!} + …} \right]\]And guess what? Those infinite sums are exactly the Taylor series for the sine and cosine functions [1]:

\[e^{\left[ \matrix{0 & -1 \cr 1 & 0} \right] t} = \left[ \matrix{ cos(t) & -sin(t) \cr sin(t) & cos(t)} \right]\]This is also the expression for a 90 degree rotation counterclockwise with some angle \(t\) [1]. How cool is that? So now we have direct mathematical proof that the matrix exponential of \(\left[ \matrix{0 & -1 \cr 1 & 0} \right]\) is exactly the 90 degree rotation matrix. This is why the matrix exponential is so useful in robot kinematics, because the matrix \(\left[ \matrix{0 & -1 \cr 1 & 0} \right]\) encodes useful information about the rotation in a skew-symmetric form [1].

References:

[1] “How (and why) to raise e to the power of a matrix, DE6.” 3Blue1Brown. 1 Apr 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O85OWBJ2ayo&list=PLZHQObOWTQDNPOjrT6KVlfJuKtYTftqH6&index=6 Visited 11 Jun 2021.

[2] Murray, R., Li, Z., Sastry, S. “A Mathematical Introduction to Robotic Manipulation.” CRC Press. 1994.