A Brief Guide to AFM Probe Selection

Recently I wrote a post describing the fundamental operating principles for atomic force microscopy (AFM). Today, I would like to follow up with a more focused discussion about the different kinds of AFM probes and how to select one for your application. I will start by talking about probe design in general, and then walk us through some different parameters that we need to consider when selecting probes, and how they affect the probe’s performance. Let’s get started!

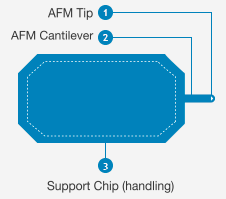

Overall Probe Design

The AFM probe is the part of the AFM setup that interacts directly with the sample surface. It is made up of three primary components: the chip (substrate), the cantilever that extends from the chip, and the tip which is on the end of the cantilever and interacts with the sample surface [1]. We manipulate the probe during set up by handling the chip, since this is the largest and most robust part of the probe. The cantilever is much smaller and extends from the end of the chip. In dynamic scanning, the cantilever is usually vibrating so we need to choose cantilever parameters that allow it to vibrate at a desired range of frequencies. Finally, the tip is the smallest, most precise part of the probe because it is the component that will interact directly with the sample. The tip is usually deposited on the end of the cantilever using a special process [1].

Figure 1 - Source: [2]

The probe is typically made using anisotropic silicon etching to a wide range of specifications. The typical lifetime of the probe is usually determined by how long the tip remains intact, and this can depend on many factors, including how aggressively the probe is used (i.e. how smoothly the tip approach is conducted, how fast scanning is done, etc.) and how experienced the user is [1]. As a noob I break a lot of my probes before I even place them in the holder; that’s how budget probe manufacturers stay in business.

Let me give you some more details on the cantilever and tip designs, since the design of these components determines the probe’s overall performance. The cantilever establishes the interaction force between the probe and the sample, and the corresponding parameter for this is the probe’s force constant. Stiffer cantilever beams have larger force constants. As I mentioned earlier, in dynamic scanning modes the cantilever is designed to vibrate, and so manufacturers will publish the resonant frequency of the cantilever as well. Finally, the coating of the cantilever is important to consider because the laser beam is incident to the top surface of the cantilever during scanning, and we want to ensure that we reflect that laser beam accurately towards the photodiode. Most coatings are optimized to be highly reflective, and the specific coating for a given probe actually depends mostly on the cantilever substrate material since certain coatings can only be applied to certain materials [1].

The tip itself is the most precise and delicate component of an AFM probe. The tip radius is an important factor to consider because this determines the smallest features you will be able to measure. You also want to choose an appropriate tip shape and aspect ratio - there are some specialized tip geometries for scanning specific features that can be difficult to access with a more standard design, such as grooves and other intricate surface geometries. You can also choose to purchase tips with specialized coatings which can help prolong their life span.

Now that we have given an overview of the parameters we need to consider when selecting a probe, let’s talk about each of them individually.

Force Constant

The force constant defines the stiffness of the probe cantilever. This is particularly important in tapping mode, where we want stable oscillations while scanning. Stable oscillations give a cleaner signal, and we can obtain them by ensuring the probe has enough stiffness (and therefore stored energy) to overcome the adhesive and capillary interaction forces between the tip and the sample surface. This means that the sample itself should also be a determining factor in your choice of force constant: if you have low adhesion/interaction forces with your particular surface, then you should choose a probe that is less stiff. This will allow the probe to still be sensitive enough to detect changes in the sample surface. Put another way, choosing a cantilever beam that is more flexible will allow it to bend to follow the surface even if the surface is not pulling on the cantilever with a lot of force.

I will primarily be scanning soft DNA samples, and for these kinds of studies it is generally recommended to choose probes with stiffnesses that are comparable to the stiffness of the sample itself, or slightly stiffer [3]. If the sample is sticky, it will be helpful to have a slightly stiffer probe that can break away from the sticky surface while vibrating in tapping mode [3]. In general, probe stiffnesses can range from <1N/m to >50N/m.

Resonant Frequency

In tapping mode AFM, the AFM control loop oscillates the probe at (approximately) its resonant frequency. So if you are choosing between two probes that have all the same parameters except for their resonant frequencies, you should typically choose the probe with the higher resonant frequency. The reason for this is that you want the tapping frequency of the probe to be as far away as possible from the scanning frequency (as determined by your scanning speed) [3]. The sample is going to respond to both the probe’s tapping frequency and scanning frequency, but if these two frequencies are far apart it is easier to isolate the sample’s response to the scanning frequency (which is much lower) from its response to the tapping frequency [3]. Also, generally samples experience less damage when probed at higher tapping frequencies. Generally resonant frequencies >300kHz are recommended.

Cantilever Coating

I’m not big on materials science so I won’t go into a lot of detail here. I think the general wisdom in regards to probe coatings is that if it’s included in the probe design you should be willing to pay for it. Gold and/or chromium coatings are pretty common and inexpensive [2].

Tip Radius

As I explained in my previous post, the probe tip radius affects the resolution of your scans in the x-y plane (the resolution in the z-direction is controlled by the piezoelectric stage that moves the sample). Sharper probe tips allow you to detect smaller features on your sample, and they also reduce the amount of error in your lateral measurements. Generally you should choose a tip radius that is smaller than the smallest features you want to measure [1]. Keep in mind that super sharp tips (i.e. <2nm) can significantly increase the cost of the probe. (Often, though, manufacturers will provide free samples that can help you find a probe that meets your needs without breaking the bank.)

One thing I’d like to point out here is that the tip is so small that it can essentially be obliterated if it experiences an electrostatic discharge. In other words, if you just walked across a carpet to get to the AFM machine and then immediately picked up a probe with your forceps, you could accidentally shock your probe tip into oblivion. One way to avoid this is not to shuffle across the carpet, but a more robust solution is to wear an ESD bracelet while handling the probes. You can get these for cheap (less than the cost of a probe, that’s for sure) from Fry’s Electronics*1 or Micro Center - they’re commonly marketed to folks who like to build their own computers.

Tip Shape, Aspect Ratio and Coating

I have not spent as much time considering these parameters so I will be more brief here. If you choose a sharp tip with a large aspect ratio (i.e. it is tall and skinny instead of being short and squat) then you can probe deeper into indentations and crevices in your sample, which may be useful [3]. However, if you want to study the forces exerted by your sample, then a probe with a larger surface area, or a shape that has been modeled analytically, may be more advantageous [3].

The tip coating contributes to its lifespan. Often you can find tips with diamond or “diamond-like” coatings that are supposed to enhance their hardness and longevity.

Q Factor

One final parameter I want to discuss is called the Q factor, or quality factor. This is a dimensionless parameter that describes how underdamped an oscillator is [4]. Specifically, it is the ratio of energy stored to energy lost in one radian of a cycle of oscillation [4]. Therefore, a large Q factor indicates that the oscillator does not lose much energy during vibration, and that the oscillations die off more slowly - i.e. a large Q factor indicates that the oscillator does not experience much damping [4]. In general, a high Q factor is desirable because this indicates that the probe will be more sensitive to the sample profile. Rectangular cantilevers generally have higher Q factors than triangular cantilevers. This parameter is not always reported by the manufacturer.

That concludes my discussion about probe selection. I plan to write another post on image artifacts commonly seen during AFM imaging, and about how to choose good scanning parameters, so stay tuned!

Footnotes:

*1 Wait, sorry, they’re out of business. RIP Fry’s, I will miss walking down your aisles admiring computer towers I can’t afford and don’t need.

References:

[1] “AFM Probe Selection.” AFM Workshop seminar. https://www.afmworkshop.com/learning-center/afm-webinars Visited 07 Apr 2021.

[2] “What is Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM).” NanoAndMore USA. https://www.nanoandmore.com/what-is-atomic-force-microscopy Visited 05 Apr 2021.

[3] Gavara, N. (2017). A beginner’s guide to atomic force microscopy probing for cell mechanics. In Microscopy Research and Technique (Vol. 80, Issue 1, pp. 75–84). Wiley-Liss Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/jemt.22776

[4] “Q factor.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Q_factor Visited 07 Apr 2021.