Tries and Suffix Trees

In this post we are going to talk about a trie (and the related suffix tree), which is a data structure similar to a binary search tree, but designed specifically for strings [1-2]. (Here we pronounce “trie” as “try”.) Each node of a trie contains a character (in general trees allow for many different data types to be stored in the nodes), and every path down the trie returns a complete word [2]. Tries and suffix trees can be used to search through large sequences, like genomes, because they make it possible to search very efficiently [1-2]. We will learn about the structure of a trie, and how it can be modified to create a suffix tree. We will also briefly review some of the operations that can be performed with tries and suffix trees. If you are interested in a Python implementation of a trie, you can see my code here, which draws heavily from [3].

Basic Structure of Tries

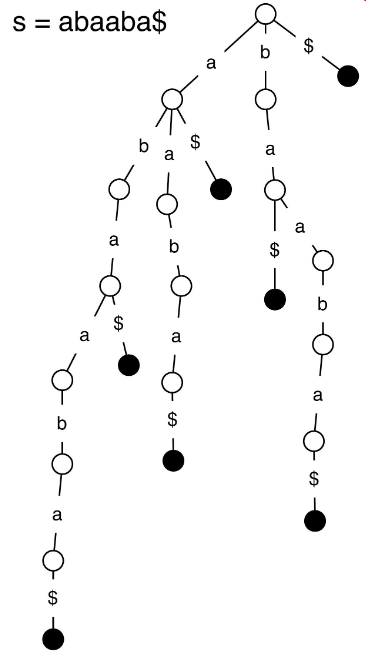

We will start this section with the trie structure, and then later we will see how we can modify it (and why we would want to do so) in order to build a suffix tree instead. A trie stores characters at each node (or along each edge as depicted in Figure 1), and any path you follow within a trie will return a completed word within the sequence you are trying to represent [1]. There are also null nodes (often $) that indicate the end of a completed word [1].

Figure 1 - Source [1]

To get an idea of why tries are so useful, imagine that we want to check if the substring “baa” is contained within our sequence. In order to do this, we start at the root node and, at each level, we choose the next node (or edge) that is the next character in our substring sequence [1]. If we are able to trace out the complete substring in our trie, then we know it is contained within the sequence [1]. The runtime to complete this query is only dependent on the length of the queried substring, not the length of the full sequence [1]. So if our full sequence is, for example, part of the human genome and therefore many thousands of characters in length, it is enormously powerful to be able to find a substring in that sequence in O(substring) time instead of O(sequence) time, where O(substring) is the length of the substring [1].*1

Tries can also be used to perform other operations like checking if a substring is a suffix or a prefix of the sequence, counting how many times a substring appears, or looking for the longest repeat of a substring in the sequence [1]. They can also be used to optimize algorithms, because if we’re looking repeatedly at related prefixes, we can save our current node in the trie and start searching from that point, instead of starting from the root node every time [2].

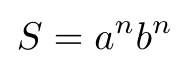

The downside to using tries is that they are very space inefficient. For example, let’s say we are storing a sequence S in a trie. Our sequence S is a series of “a”’s and “b”’s that can be expressed as [1]:

Equation 1

In this case, we have one root node, n nodes in a path of “b”’s (without “a”), and an additional n paths of n+1 “b” nodes, as shown in Figure 2 [1]. In this case, the total number of nodes that our trie must store is [1]:

Equation 2

So in essence the space requirements for a trie are a quadratic function of the length of the sequence to be stored [1]. This is not very efficient, and this is why tries are never used in practice [1]. Instead, we replace a trie with a suffix tree, which uses two important tricks to collapse the data structure so that it is much more space efficient.

Modifying a Trie to Get a Suffix Tree

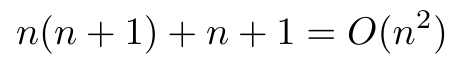

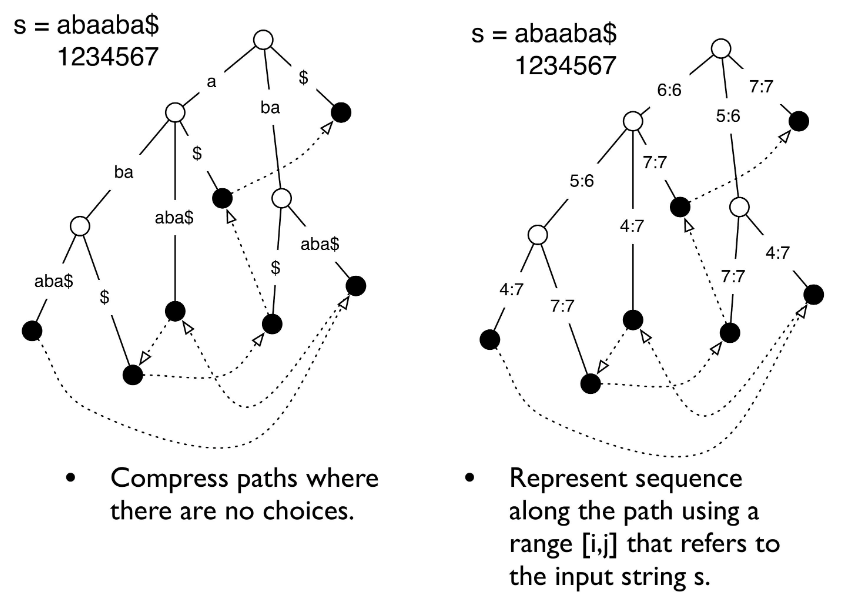

As we saw in the previous section, tries are horribly space inefficient, but there are two tricks that can be applied to them to convert them to a space efficient suffix tree. These tricks are [1]:

-

Compress paths where there are no choices. If there is a section of the trie where each node has only one child, compress that section into a single node.

-

Represent the sequence along the path using a range [i, j] that refers to a region of the input string, S.

If we apply these two tricks to the original trie shown in Figure 1, we get the new structure shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 - Source [1]

Let’s figure out what the space requirements are for this suffix tree. We can see that we have n leaves, one for each character in the string [1]. We also have approximately the same number of internal nodes as we have leaves in the tree (assuming the tree is approximately well balanced and mostly full and complete, then we approximately can apply the logic shown here) [1]. And we will need to store the ranges on each node or edge. If we assume each node (or each edge, depending on your representation) and each numeric range requires a constant amount of space, then we need a total of O(n + n + n) = O(n) space for storing our suffix tree [1]. Therefore, a suffix tree reduces the storage requirement of a trie from a quadratic to a linear relationship with the number of characters in the sequence [1]. This is why, in practice, we tend to use suffix trees over tries [1].

Footnotes:

*1 Laakmann McDowell points out that a hash table could also be used to look up if a substring is a valid word in the sequence in O(substring) time, but it could not be used to check if the substring is a prefix of a valid word in O(substring) time [2]. This is where tries have an advantage over other data structures.

References:

[1] Kingsford, C. and Ma, J. “Intro to suffix trees.” 15-351/15-650/02-613 Algorithms and Advanced Data Structures, Fall 2020.

[2] Laakmann McDowell, G. Cracking the Coding Interview, 6th edition. 2016. CareerCup, LLC.

[3] Roychowdhury, S. “Implementing a Trie in Python (in less than 100 lines of code).” Towards Data Science on Medium. 19 Dec 2017. https://towardsdatascience.com/implementing-a-trie-data-structure-in-python-in-less-than-100-lines-of-code-a877ea23c1a1 Visited 17 Jan 2021.