Message Passing Algorithms

I have been learning about how to perform inference - i.e. how to make predictions - using probabilistic graphical models. Recently, I have written about inference in general, as well as sampling methods for approximate inference. In this post, I want to explore another set of algorithms for performing exact inference using message passing.

Variable Elimination Revisited

Previously, we saw that we can use variable elimination to compute marginal probabilities. The downside to this approach is that if we changed the marginal probability of interest (i.e. instead of computing \(P(X_1)\) we wanted \(P(X_2)\)) then we would have to completely restart the algorithm and waste a lot of our computational resources. Specifically, we are wasting the fact that we computed a lot of intermediate probabilities when calculating \(P(X_1)\) that are still useful when we need to find \(P(X_2)\). We can call these intermediate factors, \(\tau\). If we can cache these values and develop an algorithm that can reuse them, we will come up with a more efficient approach to performing inference than classic variable elimination. We will call this new approach the junction tree algorithm, for reasons that will become obvious in a moment [1].

Side Note on Dynamic Programming

Variable elimination - the process of marginalizing out variables in a specific order to eliminate all but the desired variable - is a form of dynamic programming. I’ve written about dynamic programming before in the context of reinforcement learning but let me briefly define it again here. Dynamic programming, particularly in the context of computer science, is an approach that breaks problems up into overlapping subproblems, where it is possible to find the optimal solution to each of these subproblems [2, 3]. Within dynamic programming, we can solve a problem either using a top-down approach or a bottom-up approach [2].

The top-down approach is essentially the result of using recursion to solve a problem - we break the problem into subproblems (recursively) and then solve each subproblem. If the solution to the subproblem already exists (i.e. we cached it) then we just pull it directly from memory, saving computation time. Conversely, the bottom-up approach solves the smallest subproblems first and builds up to solutions for progressively bigger subproblems [2].

I mention this because we can relate both variable elimination and the junction tree algorithm to top-down vs. bottom-up dynamic programming approaches. Variable elimination computes the marginal probability of just one variable in a top-down fashion, which is why it is computationally wasteful if we want to be able to compute the marginal probabilities of many different random variables in our model. On the other hand, the junction tree algorithm is more of a bottom-up method because we will calculate and store all of the answers to the subproblems on the way to computing the marginal probability for a particular random variable [1].

Okay, now that we’ve covered that, let’s return to this new junction tree algorithm. The junction tree (JT) algorithm will make 2 passes through the graphical model using the variable elimination approach and store all of the intermediate factors, \(\tau\), in a table. We can use this table to obtain any marginal probability in constant time, that is in \(\mathcal{O}(1)\) [1]. Within the class of JT algorithms there are two forms: a belief propagation (BP) method and the full JT method [1].

Belief Propagation

Let’s start by recapping how variable elimination is equivalent to message passing in a simple example. Let’s imagine we have a small tree graph*1 and we want to compute the marginal probability \(p(x_i)\) [1]. To do this, we can set the root of the tree to be the node \(x_i\) and process the nodes in order from the leaves of the tree to the root. Since we are working with a tree structure (where there is only one path from node to node), the maximum clique size that can be formed at any point during this process is of size 2. So for example, if we are eliminating the intermediate node \(x_j\) we write [1]:

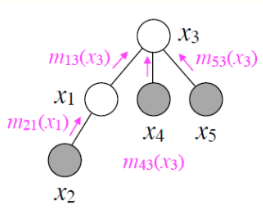

\[\tau_k(x_k) = \sum_{x_j} \phi(x_k, x_j) \tau_j(x_j)\]Where \(x_k\) is the parent of \(x_j\) [1]. These factors \(\tau\) are messages that are sent from child to parent (i.e. from \(x_j\) to \(x_k\)) which contain all relevant information about the subtree that has \(x_j\) as the root [1]. A visualization of this process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Source [1]

Once the root has received all the messages from its own children, then we marginalize them out to get the final marginal probability for \(x_i\). If we now wanted to repeat this process for a different node, i.e. to compute \(p(x_k)\), we would rotate the tree so that \(x_k\) was the root, and then run the algorithm again. Notice that the messages that \(x_j\) sent to \(x_k\) are the same as before, so if we had stored that value from the first time we ran the VE algorithm, we would be able to reuse it now. Notice that each node sends a message only when it has finished receiving messages from all of its children [1].

Now that we have the basic idea, we can formally define the belief propagation algorithm for completing two different tasks [1]:

- Sum-product message passing: for marginal inference, \(p(x_i)\)

- Max-product message passing: for MAP inference, \(\max_{x_1, …, x_n} p(x_1, …, x_n)\)

Sum-Product Message Passing

For sum-product message passing, we can compute the marginal probability for node \(x_i\) as [1]:

\[p(x_i) \propto \phi(x_i) \prod_{l \in N(i)} m_{l \rightarrow i} (x_i)\]Where \(m_{l \rightarrow i} (x_i)\) is the message from node \(i\) to node \(j\), and it can be written as [1]:

\[m_{i \rightarrow j}(x_j) = \sum_{x_i} \phi(x_i) \phi(x_i, x_j) \prod_{l \in N(i) \backslash j} m_{l \rightarrow i}(x_i)\]The product in the expression above is computed for all nodes that are neighbors of \(i\) except for node \(j\). This is exactly the same as the messages that we would pass in our conceptual discussion earlier.

Max-Product Message Passing

The logic that applied to sum-product message passing still applies here because we can distribute max operators over products just as we can distribute sums over products. So if you want to compute the partition function of a chain Markov Random Field (MRF) model for the MAP inference [1]:

\[\mathcal{Z} = \sum_{x_1} … \sum_{x_n} \phi(x_1) \prod_{i=2}^n \phi(x_i, x_{i-1})\] \[\mathcal{Z} = \sum_{x_n} \sum_{x_{n-1}} \phi( x_n, x_{n-1}) \sum_{x_{n-2}} \phi ( x_{n-1}, x_{n-2}) … \sum_{x_1} \phi(x_2, x_1) \phi(x_1)\]And if you want the maximum value of the joint, unnormalized probability distribution (called \(\tilde{p}^*\)) then we can write:

\[\tilde{p}^* = \max_{x_1} … \max_{x_n} \phi(x_1) \prod_{i=2}^n \phi(x_i, x_{i-1})\] \[\tilde{p}^* = \max_{x_n} \max_{x_{n-1}} \phi( x_n, x_{n-1}) \max_{x_{n-2}} \phi(x_{n-1}, x_{n-2}) … \max_{x_1} \phi(x_2, x_1) \phi(x_1)\]This math works for factor trees as well as chain graphs. Notice that if you wanted to know the argmax operator of the probability distribution (i.e. the most likely assignments to the variables \(x\)), then you could keep track of the best assignments of each variable \(x_i\) during this algorithm and refer back to them at the end [1].

Junction Tree Algorithm

So far we have seen how the belief propagation algorithm works on tree graphs. However, if we do not have a tree graph structure, we need to make one! Having a tree-like structure makes the message passing algorithm feasible - without it, the computations could become intractable. The full JT algorithm that we are going to present here will take an arbitrary graph and cluster the variables together, so that the clustered version of the graph has a tree structure [1]. Then we can apply the same belief propagation method as before, assuming that the local clusters can be solved exactly [1].

An Example

Let’s consider a simple example where we want to perform marginal inference over a small MRF graph which can be written as [1]:

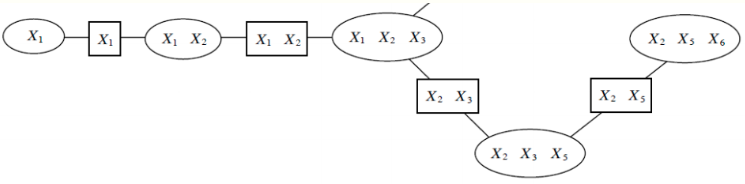

\[p(x_1, …, x_n) = \frac{1}{Z} \prod_{c \in \mathcal{C}} \phi_c (x_c)\]The cliques in the MRF must satisfy the running intersection property (RIP). Specifically, the cliques must have some “path structure” where there is a sequential ordering to them. If we have cliques \(x_c^{(1)}, …, x_c^{(n)}\), then if a variable is in both the \(j\)-th and \(k\)-th cliques, i.e. \(x_i \in x_c^{(j)}\) and \(x_i \in x_c^{(k)}\) then that variable must also be in any other cliques along the path, such as the \(l\)-th clique, i.e. \(x_i \in x_c^{(l)}\) if \(x_c^{(l)}\) is along the path between \(x_c^{(j)}\) and \(x_c^{(k)}\) [1].

Figure 2 - Source [1]. Notice that the round nodes are cliques, containing the variables within their scope. The rectangular nodes indicate the sepsets, the groups of variables at the intersection of the scopes of two neighboring cliques [1].

If our MRF graph looks like the one shown in Figure 2, then we can start to compute the marginal probability of \(x_1\) as follows [1]:

\[\tilde{p}(x_1) = \phi(x_1) \sum_{x_2} \phi(x_1, x_2) \sum_{x_3} \phi(x_1, x_2, x_3) \sum_{x_5} \phi(x_2, x_3, x_5) \sum_{x_6} \phi( x_2, x_5, x_6)\]Notice that we were allowed to push the sums into the product because the RIP assumption tells us that \(x_6\), for example, can only exist in that final cluster and not any of the earlier ones. Each intermediate factor \(\tau\) marginalizes out the variables that are not included in the scope of the next cluster. The marginalization, \(\tau(x_2, x_3, x_5) = \phi(x_2, x_3, x_5) \sum_{x_6} \phi(x_2, x_5, x_6)\), is a message being shared from one cluster to another [1].

The full JT algorithm simply adds a step to convert any graph into a tree of clusters before performing the same message passing approach that we saw earlier. Note that this “tree of clusters” is called a junction tree, hence the name of the algorithm. Let’s get some mathematical clarity on what a junction tree is. First, if we had some undirected graphical model*2 \(G = (X, E_G)\), then the junction tree \(T = (C, E_T)\) is a tree over \(G\). The nodes of \(T\), \(c \in C\), are associated with subsets \(x_c\) of the nodes in the graph \(G\), that is \(x_c \subseteq X\) [1].

The junction tree has two specific properties [1, 5]:

-

Family preservation: For each factor in the tree, \(\phi\), there is a cluster \(c\) such that the scope of the cluster is contained within the subset \(x_c\), that is \(\text{Scope}[\phi] \subseteq x_c\).

-

Running intersection: As described above, for every pair of clusters \(c^{(i)}\) and \(c^{(j)}\), the clusters on the path between them must contain \(x_c^{(i)} \cap x_c^{(j)}\).

The optimal trees have small, modular clusters, but it is NP-hard to find the globally optimal tree, unless the original graph itself, \(G\), is already a tree [1].

The Full JT Algorithm

The full JT algorithm assumes that we begin with a junction tree. We have clusters in the tree, and each cluster has a potential, \(\phi_c(x_c)\). The potentials are a product of all the factors in the graph \(G\) that have been assigned to cluster \(c\). This gives us a probability distribution over the entire graph that is the normalized product of all the clusters (this is the same as our usual UGM form) [1].

For each step in the algorithm, we choose two adjacent clusters, \(c^{(i)}\) and \(c^{(j)}\), in the tree and calculate a message to pass between them. Note that the scope of the message is the sepset \(S_{ij}\) between the two clusters (i.e. the scope is the set of nodes that they have in common) [1]:

\[m_{i \rightarrow j}(S_{ij}) = \sum_{x_c \backslash S_{ij}} \phi_c (x_c) \prod_{l \in N(i) \backslash j} m_{l \rightarrow i}(S_{li})\]Notice that \(c^{(i)}\) cannot send this message until it has received all the messages from its neighbors except cluster \(c^{(j)}\). After this algorithm finishes computing all the messages, we can define the belief of each cluster based on all the messages that it received [1]:

\[\beta_c (x_c) = \phi_c (x_c) \prod_{l \in N(i)} m_{l \rightarrow i}(S_{li})\]This belief is proportional to the marginal probability over the scope of this particular cluster. So if we wanted the unnormalized probability \(\tilde{p}(x)\) for some variable \(x \in x_c\), we could marginalize out the other variables thus [1]:

\[\tilde{p}(x) = \sum_{x_c \backslash x} \beta_c (x_c)\]To normalize this probability, we can compute the partition function \(\mathcal{Z}\) as the sum overall the beliefs in a cluster [1]:

\[\mathcal{Z} = \sum_{x_c} \beta_c (x_c)\]This algorithm runs best with small clusters, because the running time scales exponentially in the size of the largest cluster.

Shafer-Shenoy and HUGIN Algorithms

Now that we have seen the full junction tree algorithm, I wanted to note that there are also two variations on the implementation of it. Specifically, there is the Shafer-Shenoy algorithm which is exactly the full JT algorithm describe above, and the HUGIN algorithm, which is a variant of what we’ve seen. The HUGIN algorithm recognizes that whenever messages are sent or beliefs are calculated, the same messages are multiplied together several times. Therefore, the HUGIN algorithm will cache the intermediate products as it runs to save more computation time. Since the HUGIN algorithm is caching multiplication products, it will also have to divide back out some messages at certain points [6].

Footnotes

*1 A tree structure specifically means that any pair of nodes in the graph are connected by exactly one path. This means that a tree structure is acyclic. A tree is also an undirected graph [4].

*2 If you were starting with a directed graphical model you could moralize it first to obtain an undirected model, that’s fine [1]. Moralizing means that you follow a set of rules to convert the directed edges to undirected edges. It follows this kind of outdated metaphor of marrying parents that point to the same child node by adding edges between them, hence the weird name.

References

[1] Kuleshov, V. and Ermon, S. “Junction Tree Algorithm.” CS228 Probabilistic Graphical Models, 2022. Stanford University. https://ermongroup.github.io/cs228-notes/inference/jt/ Visited 14 July 2022.

[2] “Dynamic programming.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dynamic_programming Visited 13 July 2022.

[3] “What is Dynamic Programming?” Educative.io. https://www.educative.io/courses/grokking-dynamic-programming-patterns-for-coding-interviews/m2G1pAq0OO0 Visited 13 July 2022.

[4] “Tree (graph theory).” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tree_(graph_theory) Visited 13 July 2022.

[5] Urtasun, R., Hazan, T. “Probabilistic Graphical Models.” TTI Chicago, 25 Apr 2011. https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~urtasun/courses/GraphicalModels/lecture11.pdf Visited 13 July 2022.

[6] Paskin, M. “A Short Course on Graphical Models: 3. The Junction Tree Algorithms.” https://web.archive.org/web/20150319085443/https://ai.stanford.edu/~paskin/gm-short-course/lec3.pdf Visited 14 July 2022.