Bringing R-GCNs Back to MolGAN

We have talked a lot thus far about graph convolutional networks, starting with spectral graph theory, then developing an expression for graph convolution, and then modifying that expression to include directed, labeled relationships between different nodes. Now that we know more about how R-GCNs work, we are going to return to the original MolGAN paper we started with [1], and see how R-GCNs fit into the MolGAN architecture. We will begin by looking at the propagation function used by MolGAN, and then examine how the final output from several layers of convolution can be aggregated and pooled into a scalar output for the discriminator and reward function.

MolGAN Propagation Function

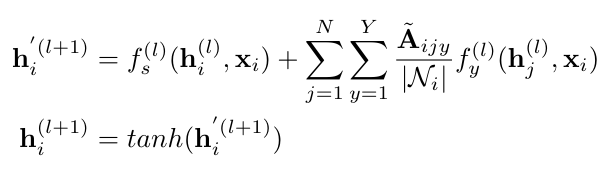

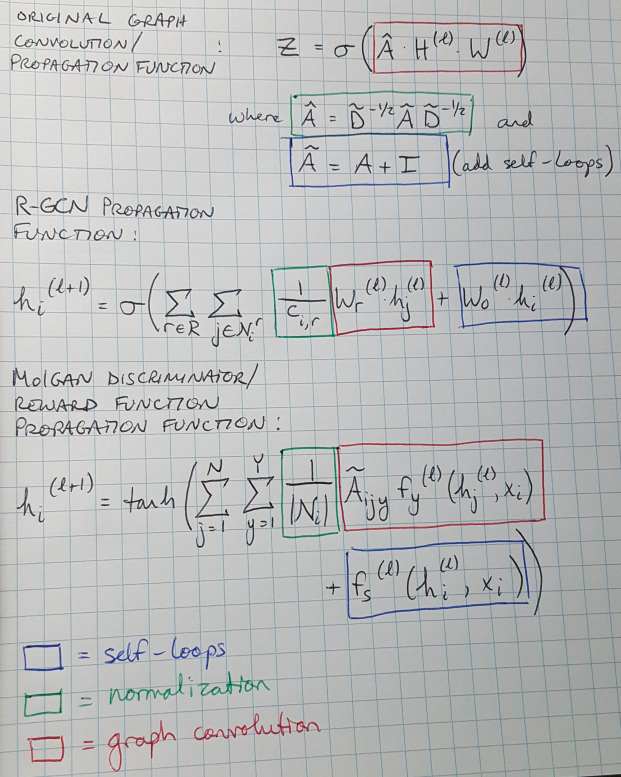

Both the discriminator and the reward function in the MolGAN architecture use an R-GCN to process the input graphs and return a scalar value [1]. Specifically, we say that the discriminator and reward function take in node signals, X, and convolve them with the graph adjacency tensor, A [1]. De Cao and Kipf write the graph propagation function for MolGAN’s discriminator and generator as follows [1]:

Equation 1

Okay, that equation is a mouthful. Let’s work through it piece by piece. First, h-i refers to the signal of the i-th node at the level indicated in parentheses [1]. The function f-s is just a linear function that adds self-connections to nodes when propagating from one layer to the next (this is similar to adding the identity function to the adjacency matrix as we discussed previously) [1]. The normalization factor, N-i, is used to scale the outputs for layer l so that they are of a similar size regardless of the number of neighbors a specific node has [1]. The factor is the size of the set of the neighbors of the i-th node [1].

The other function, f-y, is a little bit more difficult to understand. De Cao and Kipf call it “an edge type-specific affine function […] for each layer”*1 [1]. (Recall that Y is the number of bond types that we can model and N is the number of nodes [1].) I think we can argue that the multiplication of the adjacency tensor, A, with function f-y is equivalent to multiplying the adjacency matrix by the weights and the outputs of the previous layer as we did using our original graph propagation function (Equation 13 here). In fact, to help draw the similarities between Equation 1 and the previous propagation functions that we have seen, I have rewritten them and highlighted matching components in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Aggregation Function

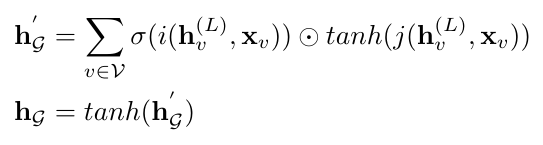

We are almost there. We now have a way to apply convolution to the input graphs over successive layers. We just need to figure out how we are going to ultimately aggregate the output of the convolution layers and return a scalar [1]. Remember: both the discriminator and the reward function are returning scalar scores to describe how well the generator produced graphs that looked real and met certain design criteria [1]. De Cao and Kipf use an aggregation function from another paper by Li et al. [2] to collect all the of the information from the convolution layers [1]:

Equation 2

Here we use sigma to represent the logistic sigmoid function (another type of activation function commonly used in neural networks) [1]. The terms i and j are used to represent two MLPs*2 that have a linear output layer [1]. The operator indicates element-wise multiplication [1]. The output from Equation 2, h, is a vector that represents the graph, G, and is passed through one more MLP layer to yield the final scalar output [1].

Why does it make sense to pass the final convolved signal with the input through two neural networks, apply different activation functions, and then multiply everything together? It seems kind of arbitrary. To understand why we structure the aggregation function this way, we turn to an explanation from Li et al. They explain that Equation 2 is in the form of a “soft attention mechanism”*3 [2]. A soft attention mechanism decides which nodes are relevant to performing the graph-level task that we are working on [2, 4]. Please see Equations 3 and 4 in the footnote below to dive into this a little more. Notice, too, that, as in Equations 3 and 4, both terms in the element-wise multiplication are the outputs of two different neural networks that are given the same set of inputs, in this case the concatenated final and initial signals, h and x.

We have come to the end of this part of our journey into exploring how MolGAN works. We have built up the theory that explains how we are able to perform graph convolution and how we apply that intuition to graphs with different kinds of edges. We have seen that both the discriminator and the reward function use R-GCNs, and they also apply a soft attention mechanism to their outputs in order to return scalar scores for the input graph.

In the next few posts, we will continue to explore various aspects of MolGAN, such as the use of the Wasserstein distance function, and DDPG. Thanks for reading!

Footnotes:

*1 I don’t know why, but every time I ask a friend to define what “affine” means, their face scrunches up and they give me this look that says “I know what it means but I can’t put it into words.” So I have turned to Wikipedia for an answer: “an affine transformation […] is a geometric transformation that preserves lines and parallelism (but not necessarily distances and angles)” [3]. So in this discussion, I think we can take the term “affine” to indicate that the group of functions f-y for all the edges have strong similarities because they preserve some features, but they are shifted or scaled to accommodate the specific bond type that they are representing.

*2 MLP = multilayer perceptron.

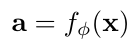

*3 A definition of attention in the context of neural networks: similar to the way we can pay attention to specific things, an attention mechanism allows a neural network to choose specific inputs to use [4]. Let’s say that we have an input vector, x, which we can pass through an attention network f with features, phi, and get out an attention vector, a [4]:

Equation 3

Now we can use a and a feature vector, z, to get out some “attention glimpse”, g [4]:

Equation 4

We define z as the output of some other neural network that also takes in x, but is parameterized with a different set of weights, theta [4]. Doesn’t this look very similar to Equation 2 above?

The output a can be described as “soft attention” if it is continuous, that is, if it can take on any value between 0 and 1 [4]. The output is “hard attention” if it must be discrete, i.e. either 0 or 1 [4]. The concept of an attention mechanism is very powerful in neural networks: it can be used to expand the space of functions that neural networks can approximate [4]. Attention mechanisms allow us to approximate more complex functions without simply adding to the number of neurons in our network [4].

References:

[1] N. De Cao and T. Kipf, “MolGAN: An implicit generative model for small molecular graphs,” arXiv Prepr. arXiv 1805.11973, May 2018.

[2] Y. Li, D. Tarlow, M. Brockschmidt, and R. Zemel, “Gated Graph Sequence Neural Networks,” 4th Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. ICLR 2016 - Conf. Track Proc., no. 1, pp. 1–20, Nov. 2015.

[3] “Affine transformation.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Affine_transformation Visited 31 Jul 2020.

[4] Kosiorek, A. “Attention in Neural Networks and How to Use It.” 14 Oct 2017. http://akosiorek.github.io/ml/2017/10/14/visual-attention.html#:~:text=What%20is%20Attention%3F,)%3A%20it%20selects%20specific%20inputs. Visited 31 Jul 2020.